Amazing Grace (2 page)

Authors: Nancy Allen

“Time to go to Grandma's,” Daddy answered, ignoring me. He clapped his hands together and smiled. Daddy's face packed a smile, but his voice didn't. Daddy's voice always had a happy ring to it when he talked to Johnny or me. Not this time.

Something about that letter, something important, made Daddy and Mom act differently. Like the time when Grandpa got hurt on the barge and had to go to the hospital. Daddy and Mom whispered a lot, serious whispers, but they told me not to worry. Every time I asked about Grandpa, they told me to think positive. I thought about the times Grandpa rode me on a wagon, the times he told me funny stories and the times he sliced open watermelons, right out of the patch, because I wanted one. I thought positive, but Grandpa died anyway.

Daddy and Mom started talking in serious whispers again. I crossed my finger and shut my eyes to think positive thoughts. I tried to wish away the something important that was in the letter, but the strange tickle in the pit of my stomach told me the wish fairy had taken the day off.

We pulled out of Hazard in our black 1938 Hudson automobile. Before long, we passed over a bridge with the sign “Troublesome Creek.” What a funny name. I poked Johnny with my elbow and pointed out the window toward the creek.

“What?” Johnny asked.

“Congratulations, you have a creek named in your honor,” I answered.

“Is it Johnny Creek?” His eyes bugged out big as quarters.

“Nope, Troublesome Creek,” I answered.

Johnny narrowed his eyes, bucked out his chin and grunted, “Humph.”

We stopped for a picnic on a wide spot beside the highway. Daddy grabbed a quilt from the trunk of the Hudson and spread it on the grass. Mom passed around biscuit-and-ham sandwiches, apples and cookies. I washed it all down with a glass of grape Kool-Aid I poured from a gallon jar.

We cleaned up our mess and crammed the trash in a brown paper sack. Daddy placed the trash and picnic supplies in the trunk and said, “Let's begin to commence to go.” I laughed at Daddy's joke; our family always took forever to get anywhere.

When I opened the Hudson's back door, Mom said, “Gracie Girl, you ride up front with Daddy. I'll keep Johnny company.”

Riding shotgun suited me fine. I loved to perch in the front seat by the driver. Besides, I was on the lookout for something.

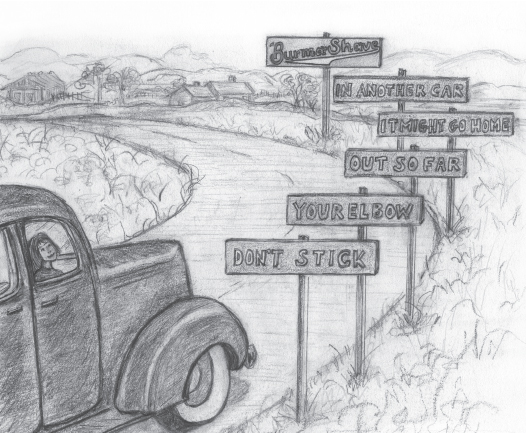

As we rounded a curve on Route 23 past Louisa, a row of Burma Shave signs popped into view. I read the signs to Johnny:

Don't stick

Your elbow

Out so far

It might go home

In another car

Burma Shave

He laughed and seemed to be over my crack about “Troublesome Creek.”

After six hours on the road, we pulled up to Grandma's house. I shot out of the Hudson as quick as a jack-in-the-box. I couldn't wait to see Grandma and discover the surprise.

Chapter 2

The Wireless

My voice exploded in a slightly off-key version of “Happy Birthday” as we marchedâI led, followed by Johnny, Mom and Daddyâthrough Grandma's door. Johnny darted around me, squealing more than singing.

Grandma's mouth fell open, and her hands flew up and covered it, but she couldn't hide the twinkle in her eyes. After we finished belting out the song, she spread her arms wide as we rushed toward her for a hello hug.

“Open your present, Grandma,” the words sprang out of my mouth before anyone else had time to speak. My itch to find out what was in that box was a prickle that needed scratching.

“Grace Ann, having my family here with me is the best birthday present of all,” she said. “I don't need anything else. Mercy, it does my heart good to see everyone.”

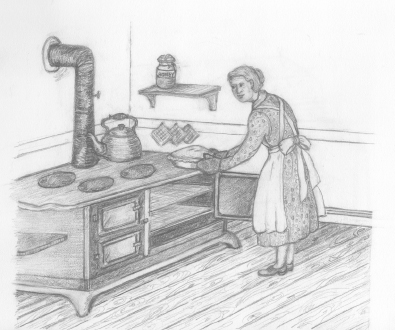

We talked and hugged some more; then Grandma said, “I'd better check on my pie.” Grandma rushed into the kitchen, and I trotted after her. As she lifted the pie out of the oven of her wood stove, she looked down at me. “It's apple. Your favorite, Gracie Girl. I used honey for sweetening. With this war going on, sugar is hard to come by. I'm thankful for my beehives.”

For the first time ever, I had my mind on something besides Grandma's hot-from-the-oven, tickle-my-tummy-good apple pie. But I also wanted to get back to the birthday celebration. “When are you going to open your present, Grandma?” I asked, jumping around with hopscotch feet.

“Well, child, I guess there is no time like the present to open a present,” Grandma answered. She fussed with the pie a minute longer. I'd been waiting on this surprise all day. Grandma's fussiness with that pie was about more than I could stand.

As I watched Grandma turn the pie and inspect it, I blurted out impatiently, “Are you going to open your present now?”

“Yes, indeed,” Grandma answered. “Now let's see what we have in that box.” She wiped her hands on her apron and followed me into the parlor.

Grandma gently lifted off the bow and, with as much care, unwrapped the box. She folded the fancy paper and said she would save it and the bow for another present. The box was a tough one. Grandma pulled and tugged at the lids, but they would not give. Daddy pitched in with a gentle pull and a tender tug. I wanted them to rip and slash the box open. Instead, they tore into it one little ole lid at a time, slow-poking around. I stood on tiptoes to try to see inside the box. I jumped up high, keeping my eyes on the open lid. Nothing worked. I couldn't see a thing but box.

The second lid popped up. I stretched my neck. I jumped again. The third and fourth lids opened wide. Grandma eased her head over the wide box and gazed inside. She looked up at Daddy and asked, “Son, what is this thing?”

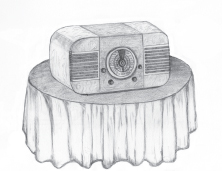

“It's a radio, Ma,” Daddy explained. “It's called a wireless. You can listen to the news instead of having to wait for the newspaper. You can listen to music too.”

“I've never listened to a wireless,” Grandma declared. “But I've heard of it. Some of my neighbors have them, but I've had no need for one.”

“It's 1944,” Daddy said, “and high time you entered the modern world.”

“Uh huh,” Grandma muttered as she stared at the wireless.

“Especially now that people want to know what's going on with the war,” Mom said. “We'd have a wireless ourselves, but there's no radio station in Hazard.”

By the time Daddy got the wireless out of the box and set it on a table, I was bouncing around like a kernel of popcorn in hot oil. By the time he turned the knob, my kernel popped. I stood there, in the middle of the parlor, and listened.

The magic box was a cube of shiny brown wood, a little more than a foot tall, a foot wide and a foot deep. Knobs adorned the face of the wireless to turn the radio on and off, to adjust the volume and to dial in a station. The dial was a circle shape with numbers wrapping around the edge like a clock. It even had a hand like a clock. With a twist of the knob, the hand found a number on the dial. Daddy turned the knob back and forth, adjusting it to find the best sound from the station. Holes covered with cloth surrounded the dial, and words and music flowed out of the holes.

I hummed along as I listened to the music gushing out of the magic box. My arms swayed like kites in a gentle breeze to a slow tune, but when a “Cow Cow Boogie” tore loose, so did my feet. I felt the rhythm, and the rhythm carried me around the room, sashaying to the beat. I pranced a sassy dance, flinging my arms, tossing my head and tapping my toes as I swiped a polished path on Grandma's already shiny floor.

“Shoo-Shoo Baby” set Johnny wiggling like nobody I'd ever seen. He slapped his knees, flapped his arms, twisted and turned and flipped and flopped, bouncing to the music in his own style of a hoedown.

As Daddy adjusted the dial to get better sound, he said, “Some folks say an Italian named Marconi invented the radio back in 1895, but other folks say it was none other than Mr. Nathan Stubblefield over at Murray, Kentucky. Word has it that Stubblefield showed off his radio a good three years earlier, in 1892.”

“Did Mr. Stubblefield talk or play music the first time he showed off his radio?” I asked.

“I heard he spoke a few words and then played a French harp,” Daddy answered. He fiddled with the dial, and more music flowed out.

I stopped dancing when the music stopped, but Johnny never slowed down. A man's voice inside the box talked about the singer, Judy Garland. He said Miss Garland played Dorothy in

The Wizard of Oz

. I loved that book. Then he said, “Here's a song sung by none other than Miss Garland herself, along with Gene Kelly.”

I was almost afraid to breathe, afraid I'd miss a note, as I listened to their warm-buttered voices sing “For Me and My Gal.”

After the song finished playing, I moseyed over and laid my hand on the magic box, feeling the thrill of the touch. The voice in the box talked about Berkeley razor blades being the sharpest.

“That's the kind I use,” Daddy said. He listened, like me, to every word coming out of the wireless.

A knock at the door caught our attention. Grandma's next-door neighbor, Dorothy, had dropped by. Dorothy tuned her ears to the wireless for a few minutes and vowed and declared that she was getting a radio before the week was up, if she could find one. “Radios are hard to come by with the war going on,” she said.

We listened to the ventriloquist Edgar Bergen and his dummy, Charlie McCarthy. Johnny giggled and slapped his leg at their jokes. Other neighbors stopped by to listen and talk about the war. All took a shine to the wirelessâall but Grandma.

“There's nothing to be gained by listening to a talking box,” Grandma said as she sat down on her settee and picked up her knitting. “That wireless is a waste of time and money. A pure and simple waste.”

Daddy laughed. “Ma, you'll grow to love the wireless. Just give it some time to get used to.”

“Son, I've done all the growing I've a mind to,” Grandma declared. “I'm much too old to get used to new foolishness.”

Daddy turned a knob, and the music swirled louder, filling the house with “A Lovely Way to Spend an Evening” by Frank Sinatra. Daddy held Mom's hand and danced around the parlor, into the kitchen and back again. They swayed as smoothly as honey dripping from a jar and looked as sweet.

When a slow tune began to play, Daddy said, “Let's dance, Gracie Girl.” He and I swayed around the settee in what he called a waltz. We glided across the room as if we were floating on air.

But when Tommy Dorsey and his orchestra played “Boogie Boogie,” Daddy grabbed Johnny. They hopped and skipped, pranced and danced, romped and stomped out on the front porch and back. Johnny squealed with laughter and clapped his hands.

When the next song played, Grandma walked into the kitchen and set plates and glasses on the table for supper. Daddy followed. He took Grandma's hand, bowed at the waist and said, “Ma'am, may I have this dance?”

“I'll have no part of this foolishness,” Grandma said, sliding her hand out of Daddy's grip. “That talking box is nothing more than a way to while away your time. No good will come of it. Mark my words and see.” Grandma went back to setting the table, this time with forks and knives.