Alphabetical (29 page)

Authors: Michael Rosen

PRONUNCIATION OF THE LETTER

This is âB's close relative, as it is the âunvoiced' form of âB', a sound made by using the lips as a kind of dam, which then open, pushing out breath.

âP' combines with âr', âl' and âh' to make âpray', âplay' and âphone'. It combines silently with ât' to make âptarmigan' and with âs' in the prefix âpsycho-'. One of my surprises when speaking French, is pronouncing the âp' in âpneu' and âpsycho'. Modern phonics teaching doesn't call these âsilent' but says that âpt' and âps' are rare ways of making the ât' and âs' sound. Before a âp' you can put other consonant sounds to write words like âjump', âlisp' and âpulp'. One of my favourite books when I was a boy was called

Kpo the Leopard

which I rather enjoyed saying.

Like most other consonants, âp' can end words without being doubled, as with âcup', but it is then doubled in âhop, hopping, hopped' though not in âhope, hoping, hoped' because of the long vowel preceding the âp'.

âP-words' can indicate smallness: âpip', âpeep', âpop', âpup', âpap', âpee-pee', âplip', âplop' and âpitter-patter'.

Other sound-play can be found in âPippa', âthe Pied Piper', âpoo-poo', âPoppy', âpip-pip' and âhe's a people person'. We seem to like saying, âPity the poor person who . . .'

Printers had to âmind their ps and qs'. Moveable type is in mirror form. It's very easy to select a âp' for a âq' and vice versa when picking out the letters to put in the press. That's one story, anyway.

T

HERE'S A GRAVE

in Sydney on which there is the following inscription:

IN LUVING MEMORI OV JACOB PITMAN, BORN

28

NOV.

1810

AT TROWBRIDGE. ENGLAND, SETELD IN ADELAIDE

, 1838,

DEID

12th

MARCH

1890

ARKITEKT INTRODIUST FONETIK SHORT HAND AND WOZ THE FERST MINISTER IN THEEZ KOLONIZ OV THE DOCTRINZ OV THE SEKOND OR NIU KRISTIAN CHURCH WHICH AKNOLEJEZ THE LORD JESUS CHRIST IN HIZ DIVEIN HIUMANITI AZ THE KREATER OV THE YUNIVERS THE REDEEMER AND REJNERATER OV MEN GOD OVER AUL. BLESED FOR EVER.

It's a testimony to some extraordinary projects. The gravestone, erected by Jacob Pitman's brother Isaac, is a tribute to four of them: the world's first phonetic shorthand, a phonetic alphabet, the âNew Church' and the world's first correspondence course. The inscription is itself written in Isaac's new phonetic alphabet; and the fact that it was possible to introduce shorthand to

Australia was a result of his realizing that if he could cram his shorthand textbook on to one small card, he could benefit from the newly invented Penny Post and send it all round the world, including to his brother Jacob in Adelaide.

If we roll this up into one ball of human energy, we can see that Isaac Pitman devoted himself to a utopia: with his phonetic alphabet, a new kind of written word would relate directly to the way in which people spoke. This would mean that everyone would be able to read and write easily. With another writing system he devised â phonetic shorthand â the way people spoke could be accurately transcribed and the transcription would keep up with the speed of speech. Nothing need be missed. As a result of both systems, the word of the true God (Jesus Christ) would be universally available and we would all be redeemed. As great literature would become accessible to all, everyone would become enlightened. If people could write faster, it would save time and, as Isaac Pitman said, âto save time is to prolong life'.

Just to be clear â Pitman grew up in a world unlike ours in one particular respect: no means existed by which speech could be preserved and played back. The nearest that people could get to it was in writing dialogue in novels, plays and poems. A thing spoken was a thing gone. Of course, people had memory and they could imitate each other, but, unlike us, they didn't live in a world surrounded by electronically recorded speech. So, Pitman's two inventions were revolutionary: with strokes of the pen, everyone would be able to write down, in a much more consistent way than using the alphabet, the sounds of their speech (âphonemes'); and specialists would be able to learn a shorthand which for the very first time captured every phoneme as it was spoken.

Isaac Pitman was born in 1813, in Trowbridge, Wiltshire, the

son of a hand-loom weaver. He left school at the age of twelve, because he couldn't cope with the tiny classroom jam-packed full. It seems as if there were words he couldn't pronounce â or thought he couldn't pronounce â but he joined what was one of the first lending libraries and proceeded to educate himself. One key book for him was

Walker's Critical Pronouncing Dictionary and Expositor of the English Language

.

When you read the opening pages of this book, it's easy to see how Pitman's reading of it set him on the path he chose for the rest of his life and, as a result, he changed the lives of millions of people â especially working-class women. The title page of Walker's dictionary is a statement of intent, showing how meaning, pronunciation and standardization were parcelled up together under the guidance of ancient Greek and Latin â two languages that no one knew how to pronounce anyway! The alphabet's life in Britain had never before received such a going over. Young Pitman pored over how Walker undertook to explain meaning, indicate how words should sound and why, define rules of pronunciation, examine the influence of ancient languages, lay down specific rules for the Scots, the Irish and Londoners, and even give advice to foreigners on how to use the dictionary.

Pitman set himself the task of learning the words and the right way to pronounce them. He would have seen very quickly that Walker hadn't tried to reform spelling with the purpose of ensuring that the twenty-six letters of the alphabet would represent sounds more consistently. What he had done was extend the use of the letters by adding a host of little signs (âdiacritics') placed over letters to indicate what their âaccent and quantity' should be. It doesn't seem to have occurred to Walker that the ânatives of Scotland, Ireland and London' might not want to âavoid their respective peculiarities' or, indeed, that they might

find it too much bother to unlock his adapted alphabet purely in order to talk the way he thought they should.

The young Pitman seems to have been transfixed by the book and he proceeded to learn all 2,000 words and their correct pronunciations. By 1837, he had devised and written down in his notebook the world's first ever phonetic shorthand system. I was able to see this notebook in the Pitman Archive at Bath Spa University and I can admit to âhaving a moment'. One of the mysteries about my mother was that she could listen to what we were saying, fill a page with little squiggles and then read back to us exactly what we had said. Though she was a âscholarship girl' and had gone to the grammar school, her parents didn't think that staying on in the sixth form or going to university was the right thing for a working-class Jewish girl to be doing. So she went to secretarial college and learned shorthand and typing, which enabled her to work as a secretary first at a newspaper and then at the Kodak factory. My holding Pitman's notebook was to look at what had enabled my mother, exactly 100 years after Pitman's invention, to get her first job, to delight her sons with her scribbles and to turn my father's extempore thoughts into beautifully typed lectures.

Pitman published his shorthand in a twelve-page booklet in 1837 as

Stenographic Sound Hand

. By 1840, it was called

Phonography

. He reduced the information required to learn it so that it fitted on to a single piece of paper and in 1840, when the Penny Post came in, he began sending these out around Britain and all over the world.

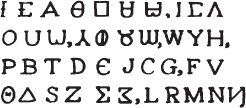

By 1844, Pitman (along with A. J. Ellis) had produced a reformed spelling alphabet that looked like this:

With these two alphabets (the shorthand and the reformed spelling alphabet), coupled with his prodigious energy, Pitman now pursued what he himself called the âcause'. He travelled and lectured, published books, edited journals. He canvassed support, wrote letters and articles; he organized a âPhonographic Festival'. He tried to convince educators to teach both the shorthand and his âPitman Alphabet' of 1844 â âshort hand will be the common hand,' he proclaimed.

Pitman drew some praise but more fire from various quarters, including a reverend and a Quaker poet, seeing respectively the hand of Satan in the new system or calling it little more than âparrot lore'. The vegetarian, teetotal, non-smoking, heavily bearded Pitman pressed on, driven by his desire that âevery boy should have the opportunity of acquiring the art'. One blot on the page was that his second wife found out that a young woman admirer was writing to him in shorthand. Mrs Pitman engaged the services of a trained practitioner and put a stop to it. In the great alphabetic struggle, we know now that Pitman shorthand won; the Pitman alphabet lost. It seems as if you can âre-form' the alphabet for specialists but you can't reform the alphabet for everyone.

In the Pitman Archive, they have many documents which chart these battles but one item trumps the lot. In 1891, Pitman was due to give an address to the National Phonographic Society

but he was busy elsewhere, so he recorded an address on the new technology of the wax cylinder. In his strong Wiltshire accent â with what sounds to my ear a bit like a mix of Irish and American â he talks of the âcombined labours of very enthusiastic phonographers who have worked with me for fifty-four years perfecting a brief representation of the sounds of speech' and adds that these labours have extended âphonography to all parts of the earth where English is spoken'.

I wonder if Pitman had any sense that the apparatus on which he was recording his voice would over time drastically reduce the number of people who would use his phonographic shorthand. Dictaphones, âtelediphones', ârapid transcription services', reel-to-reel tape machines, cassette machines, minidiscs, digital recorders, PCs, laptops, iPads and iPhones would all eat away at the need for shorthand. My students record their lessons on something that's the size of a pen, put earphones on and transcribe it. A journalist from a newspaper interviews me and puts what looks like an alloy packet of cigarettes on the table between us. Shorthand teachers bewail the loss of the skill, pointing out that the journalist who uses shorthand is the one who listens and notes what's important. Perhaps Pitman should have sent his message to the National Phonographic Society in shorthand.

Looking at Sir Isaac Pitman from the vantage point of today, we can see that he stands in two alphabetical streams: one concerns the wish or need to write quickly (usually called âshorthand'); and the other is the wish or need to make writing easier (usually called âspelling reform', though this might involve reform of punctuation or of the letters of the alphabet).

As I've said, the point about Pitman shorthand was that it was the first attempt to write quickly by using symbols for sounds we make (âphonemes'). Before and since, most shorthands have involved inventing squiggles or abbreviations to make

the business of writing words shorter. I can remember sitting on an underground train in the 1950s looking at an advert which addressed us passengers with âGt a gd jb nd mre py.' I think it was called âSpeedwriting'. Pity they weren't more wholehearted about it and called it âSpdwrtng'.

The term âshorthand' has alternatives: the actual process of writing in any kind of shorthand is âstenography', though it has also been called âbrachygraphy' and âtachygraphy' (three Greek prefixes are more than enough for anyone in one sentence but âstenos' means ânarrow', âbrachys' means âshort' and âtachys' means âfast'), each of which indicates some sense of what was intended.

The Parthenon in Athens can claim to hold the oldest shorthand. A marble slab dating from the mid-fourth century

BCE

indicates that the Greeks used a shorthand based on vowels. I'm not sure that would work in English. That Speedwriting ad would read: âE A OO O A OE A'. Two hundred years later, in Hellenistic Egypt, we hear that it will take one Apollonios two years to learn shorthand. That method was to take âword stems' with signs for word endings. An equivalent in English would be to take a âstem' like âplay' and use a sign on the end for âs' when it's âplays', another for â-ed' when it's âplayed' and another for â-ing' when it's âplaying'. These three signs could then be used for all verbs with â-s', â-ed' and â-ing' endings.