Almost Heaven (44 page)

I just would like to say, a lot of people didn't know Billy. But Billy poured his life into serving God. And I know when he walked into heaven yesterday, heaven knew Billy. He was an important person to them.

When I read her e-mail, my first response was “I know this man.” I didn't know him personally, but I knew his stock. I knew what drove him to start that station in Lost Creek, West Virginia. I wrote Carmeleta back and asked if she would come on with us for a few minutes and share what Billy meant to her. When she finished, we moved on to another topic, but Billy haunted me. I told my wife later that week, “I think I have my next story.”

Everything in this book is from my imagination. As far as I know, there are only shadows from Billy's real life. But I hope in crafting this story that I have captured a little of his heart. I'm grateful to Carmeleta and her husband for sharing their stories of Billy. Of course, I would thank Billy for the way he lived and how he showed God's love. Someday I will meet him face-to-face.

I also want to thank others who have made this story possible. Karen Watson is the top dog in fiction at Tyndale, but you would never know it. She has listened to every idea I've thrown at her and even gave the okay when I asked to put an angel in my story. Sarah Mason performed major surgery on this manuscript, and for that Billy and I both are thankful.

Kathryn Helmers is another constant. Without her encouragement early on, I would still be looking for a publisher.

To my familyâmy wife, Andrea; my children, Erin, Megan, Shannon, Ryan, Kristen, Kaitlyn, Reagan, Colin, and Brandonâyou mean more than life. Thanks to David and John; Susan and Kim; my parents, Robert and Kathryn Fabry; and my father-in-law, George Kessel, for your support through our desert experience. I wish Barbara could have read this story.

Thanks to Robert Sutherland for friendship and more. The dog, Rogers, was an amalgam of our dearly departed Pippen and Frodo.

There is a rich history of bluegrass in the Mountain State, and I listened to a lot of it as I wrote. Thanks to Mickey Halleron for his technical assistance, music, and memories.

And thanks to the one who gives us music, who shows us beauty amid the ashes, and who uses pain to make songs sweeter and more satisfying. To you be honor and glory forever. Amen.

Chris Fabry

Tucson, Arizona

About the Author

Chris Fabry is a 1982 graduate of the W. Page Pitt School of Journalism at Marshall University and a native of West Virginia. He is heard on Moody Radio's

Chris Fabry Live!

,

Love Worth Finding

, and

Building Relationships

with Dr. Gary Chapman. He and his wife, Andrea, are the parents of nine children. Chris has published seventy books for adults and children. His novel

Dogwood

won a Christy Award in 2009. You can visit his Web site at www.chrisfabry.com.

Reading Group Questions and Topics for Discussion

1. At the end of the first chapter, Billy finally reveals how he was really saved from the flood. Have you ever experienced a situation like that, where something happened to you that you couldn't explain?

2. What were your first impressions of Malachi? Was he what you would have expected an angel to be like? Why or why not?

3. At the beginning of chapter 3, Billy says, “I have heard that your first childhood memory is telling.” What is your first childhood memory, and what do you think it says about you?

4. In chapter 8, Malachi observes that Heather was being pulled away from God by her own passions, and he assumed that is why the enemy left her alone. Is that reassuring to you or convicting?

5. In chapter 10, Billy faces one of the most difficult decisions he's ever had to make concerning the care of his mother. Did you identify with Billy's actions? Have you ever had to make a similar decision? How did you handle it?

6. Throughout the story, many people extend small acts of kindness toward BillyâAdrian Rogers, Callie, Charles Broughton. Has anyone ever extended similar kindnesses to you? How did it make you feel?

7. At times, it feels like Billy loses just about everything he loves. One of the demons even remarks that everything he touches withers and dies. How do you think Billy feels about his life? Why? If it would have been easier for Billy to stay in his shell, why does he take the risk he does?

8. In chapter 16, Billy says that to many, “God is not someone you know but something you try to get off your back.” Have you felt this way at some point in your own life? How do you see this play out in our society?

9. Throughout the story, how do you see God showing his love for Billy, even at times when Billy doesn't recognize it? Can you think of similar examples of God's love in your own life?

10. An event in Billy's teenage years affects him greatly. How was Billy finally able to overcome the effects of that event? Have you ever faced a traumatic event, and how did you overcome it?

11. In chapter 27, Malachi wrestles with the fact that he was called away by God during a crucial time in Billy's life. Back in chapter 7, Malachi's commander had warned him about this, and told him that the “events to come must occur.” How did this make you feel?

12. Though Callie had a strong faith, she reached a time when that faith wavered and she became susceptible to evil. What brought her to that point?

13. What do you think Malachi took from his observance of Billy's life? Where do you think Malachi was sent next?

14. In

Almost Heaven

, we learn a lot about people like Billy, Callie, Natalie, and Sheriff Preston. How do you picture them five years after the close of this story?

15. After reading the story, what did you admire most about Billy Allman?

From

June Bug

Some people know every little thing about themselves, like how much they weighed when they were born and how long they were from head to toe and which hospital their mama gave birth to them in and stuff like that. I've heard that some people even have a black footprint on a pink sheet of paper they keep in a baby box. The only box I have is a small suitcase that snaps shut where I keep my underwear in so only I can see it.

My dad says there's a lot of things people don't need and that their houses get cluttered with it and they store it in basements that flood and get ruined, so it's better to live simple and do what you want rather than get tied down to a mortgageâwhatever that is. I guess that's why we live in an RV. Some people say “live out of,” but I don't see how you can live out of something when you're living inside it and that's what we do. Daddy sleeps on the bed by the big window in the back, and I sleep in the one over the driver's seat. You have to remember not to sit up real quick in the morning or you'll have a headache all day, but it's nice having your own room.

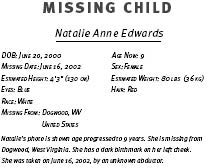

I believed everything my daddy told me until I walked into Walmart and saw my picture on a poster over by the place where the guy with the blue vest stands. He had clear tubes going into his nose, and a hiss of air came out every time he said, “Welcome to Walmart.”

My eyes were glued to that picture. I didn't hear much of anything except the lady arguing with the woman at the first register over a return of some blanket the lady swore she bought there. The Walmart lady's voice was getting all trembly. She said there was nothing she could do about it, which made the customer woman so mad she started cussing and calling the woman behind the counter names that probably made people blush.

The old saying is that the customer is always right, but I think it's more like the customer is as mean as a snake sometimes. I've seen them come through the line and stuff a bunch of things under their carts where the cashier won't see it and leave without paying. Big old juice boxes and those frozen peanut butter and jelly sandwiches. Those look good but Daddy says if you have to freeze your peanut butter and jelly sandwiches, then something has gone wrong with the world, and I think he's right. He says it's a sin to be mean to workers at Walmart because they let us use their parking lot. He also says that when they start putting vitamins and minerals in Diet Coke the Apocalypse is not far behind. I don't know what the Apocalypse is, but I wouldn't be surprised if he was right about that too.

You can't know the feeling of seeing your picture on a wall inside a store unless it has happened to you, and I have to believe I am in a small group of people on the planet. It was all I could do to just suck in a little air and keep my heart beating because I swear I could feel it slow down to almost nothing. Daddy says a hummingbird's heart beats something like a million times a minute. I was the opposite of a hummingbird, standing there with my eyes glued to that picture. Some people going outside had to walk around me to the Exit doors, but I couldn't move. I probably looked strangeâjust a girl staring at the Picture Them Home shots with an ache or emptiness down deep that I can't tell anybody about. It's like trying to tell people what it feels like to have your finger smashed in a grocery cart outside when it's cold. It doesn't do any good to tell things like that. Nobody would listen anyway because they're in a hurry to get back to their houses with all the stuff in them and the mortgage to pay, I guess.

The photo wasn't exactly me. It was “like” me, almost like I was looking in a mirror. On the left was a real picture of me from when I was little. I'd never seen a picture like that because my dad says he doesn't have any of them. I've gone through his stuff, and unless he's got a really good hiding place, he's telling the truth. On the right side was the picture of what I would look like now, which was pretty close to the real me. The computer makes your face fuzzy around the nose and the eyes, but there was no mistake in my mind that I was looking at the same face I see every morning in the rearview.

The girl's name was Natalie Anne Edwards, and I rolled it around in my head as the people wheeled their carts past me to get to the Raisin Bran that was two for four dollars in the first aisle by the pharmacy. I'd seen it for less, so I couldn't see the big deal.

I felt my left cheek and the birthmark there. Daddy says it looks a little like some guy named Nixon who was president before he was born, but I try not to look at it except when I'm in the bathroom or when I have my mirror out in bed and I'm using my flashlight. I've always wondered if the mark was the one thing my mother gave me or if there was anything she cared to give me at all. Daddy doesn't talk much about her unless I get to nagging him, and then he'll say something like, “She was a good woman,” and leave it at that. I'll poke around a little more until he tells me to stop it. He says not to pick at things or they'll never get better, but some scabs call out to you every day.

I kept staring at the picture and my name, the door opening and closing behind me and a train whistle sounding in the distance, which I think is one of the loneliest sounds in the world, especially at night with the crickets chirping. My dad says he loves to go to sleep to the sound of a train whistle because it reminds him of his childhood.

The guy with the tubes in his nose came up behind me. “You all right, little girl?”

It kind of scared meânot as much as having to go over a bridge but pretty close. I don't know what it is about bridges. Maybe it's that I'm afraid the thing is going to collapse. I'm not really scared of the water because my dad taught me to swim early on. There's just something about bridges that makes me quiver inside, and that's why Daddy told me to always crawl up in my bed and sing “I'll Fly Away,” which is probably my favorite song. He tries to warn me in advance of big rivers like the Mississippi when we're about to cross them or he'll get an earful of screams.

I nodded to the man with the tubes and left, but I couldn't help glancing back at myself. I walked into the bathroom and sat in the stall awhile and listened to the speakers and the tinny music. Then I thought,

The paper says my birthday is June 20, but Daddy says it's April 9. Maybe it's not really me.