All the King's Men

Read All the King's Men Online

Authors: Robert Marshall

All

The King’s

Men

Robert Marshall

To the memory of my mother

and the love of my wife

Contents

Preface

I ‘The French Kid Glove…’

II ‘…The Hand of Albion’

III The Fall

IV Organization

V To England

VI Prosper

VII The Trojan Horse

VIII The Rules of the Game

IX An Eastern Influence

X Down to Business

XI The Other Game

XII In the Wilderness

XIII Consequences

XIV Cockade

XV Denunciation

XVI Arrangements

XVII Trials

XVIII Afterwards

Bibliography

References in the Text

Footnotes

A Note on the Author

The major SOE networks in June 1943

During the summer of 1943, Britain’s wartime secret service, the Special Operations Executive – SOE – suffered a major collapse of its networks in northern France. It was a disaster of monumental proportions, a disaster from which the SOE never properly recovered. The story of that collapse lies at the very heart of the history of Britain’s secret war alongside the French Resistance. It is a story that is engraved upon the memories of those who were there and survived. For apart from the terrible loss of life and

materiel

, the collapse precipitated a serious crisis of confidence. After the war, stories proliferated – on both sides of the Channel – of betrayal, deception and English perfidy. An official history went to considerable length to silence these rumours, and for a while it succeeded. But the passing years nurtured old suspicions. If one picks up a well-read copy of

The SOE in France

, it will invariably fall open at the events surrounding the collapse of the northern networks and the role played by an individual by the name of Henri Déricourt. What makes these few pages so fascinating is that they raise more questions than they answer.

In fact all accounts of the events in France during 1943 are less than satisfying simply because authors have been hampered by the singular inaccessibility of the relevant material. All SOE’s records are held in perpetual custody by the Secret Intelligence Service (MI6). Time, a little good fortune and a great deal of effort have shaken some of this material free. This development, coupled with the

recollections of veterans and survivors and of many others not previously connected with the story, now makes it possible to produce a realistic, though hardly agreeable, explanation for SOE’s very worst disaster.

The research for this book began when Roy Davies, editor of the BBC’s history series TIMEWATCH, suggested I look into the subject as a possible item for that programme. In the course of its making an enormous amount of new material was uncovered – too much to be squeezed into one hour of television. This volume is, therefore, a golden opportunity to present that material in as much detail as the narrative will allow. I am indebted to a great many people who contributed much to the research and who deserve proper recognition. Daniella Dangoor, who combed the French archives exhaustively; Dr Stephen Badsey, military historian, who volunteered his time and knowledge in areas that were remote from my experience; Dr Katherine Herbig at the US Naval College in Monterey, California, an expert in strategic deception, who allowed me access to many papers unavailable in Britain; and finally – but most importantly – Larry Collins, author of

Fall from Grace

, who allowed me to read the typescripts of a great many invaluable interviews that were recorded with people now long dead.

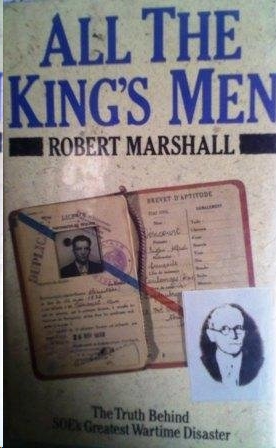

The most valuable archival material that was uncovered was found in the private papers of Henri Déricourt. These contain his pilot’s log books and licences, birth and marriage certificates, letters, financial records, military records, forged documents, a manuscript for a novel together with a vast quantity of miscellaneous trivia – even a receipt for his coffin. The name Déricourt is perhaps not so well known as Burgess or Maclean, but nevertheless he deserves to be recognized as one of the most accomplished intelligence agents of all time.

The bulk of the detail contained in this book is drawn from interviews with over fifty veterans and survivors of the secret war. These included some half dozen SS and SD

officers in Germany; a number of pilots and crew who flew with Déricourt over the years; SOE officers; and countless members of the French Resistance. A surprising number of retired MI6 officers have also spoken to me freely about their work, and about Claude Dansey in particular. In fact it was the character of Dansey that proved the most difficult to unravel. A great deal of unhelpful hagiography has been written about this man, a complex individual who remained an enigma even to those who worked closest with him. Trying to weave one’s way between those who thought him a god and others who believed he was the Devil incarnate proved a difficult task. Whether he was a madman or a genius is one of those MI6 mysteries that remain at best only half answered.

Robert Marshall

Perth, Australia, March 1987

During the winter of 1946, locked away in Fresnes Prison in the southern suburbs of Paris was a bleak and friendless community of souls. They had been thrown together by the final scenes of an exhausting war. Down the long central gallery, dimly lit by pools of grey sunlight, hundreds of wretched Frenchmen took their regular stroll from the cells to the little cubicles where they could meet their lawyers. A disparate group of frightened and bitter men, united by a single crime – collaboration. Paradoxically, just three years before, Fresnes Prison had echoed to the sound of jackboots and the inmates who padded along the gallery then also shared a common charge. They called it Patriotism. The world had been turned upside down. Of course, not all the inmates the Germans imprisoned there in 1943 were true patriots and nor indeed were all those imprisoned in 1946 guilty of treason.

The prisoners in Fresnes were part of a larger society that was gradually steeling itself for a painful period of self-examination. France was emerging from one of the darker chapters in her long history. She had not been united by war, but shattered into a hundred fragments. The presence of the Nazi occupiers had encouraged some Frenchmen of a fascist persuasion to embrace the invader – in the name of France. Although the vast majority, faced with the reality of defeat, had quietly accepted collaboration as the prescribed antidote to national humiliation, a few, a very few, presumed to resist the invader and live as underground terrorists.

As the tide of war had turned, the ranks of the resisters swelled, the collaborators became more unwilling and the Fascists were isolated. French society was wrenched first one way and then the other.

Isolated from the great social upheavals, there inevitably flourished a few who cared nothing for the politics of the thing, but who saw the whole great conflict as nothing more than a fabulous game, to be played either for profit or glory – or just for the thrill of it. And if they found themselves on the wrong side of the wall at Fresnes, it was often no reflection on how well they had played the game.

Prisoner Déricourt – number 13.181 – spent hours at his tidy little desk in cell 1/459, agonizing over the words to address to his uncomprehending wife. The monthly letter had become something of a struggle between what he would have liked to have said and what she needed to hear.

My beautiful chicken…

I’ve just received your letter of Wednesday. My poor chicken’s nerves are having a hard time. And as you say, when will it end? For myself I don’t know, for it’s not me who decides. But they will have to release me for I have done nothing wrong.

1

On 22 November 1946, he and his wife had been sitting down to their dinner when three officers of the DST (Département de la Surveillance du Territoire), the French equivalent of Britain’s MI5 (the Security Service), arrived to arrest Henri Eugène Alfred Déricourt on a charge of treason. They apologized for having called at such an inhospitable hour, then splayed themselves across the armchairs and waited for the couple to finish their meal. Occasionally they made an attempt at conversation but Déricourt was utterly taciturn and gave the impression of a man absorbed in his meal. His wife, Jeannot, or his ‘little chicken’, as he called her when trying to comfort, was temperamentally a different person. Petite and somewhat nervous, she had tried but failed to disguise her terror and

so Henri had leant across the table, taken her hand in his and held it there.

When he had finished, Déricourt packed a small bag with toothbrush, soap and towel. Then he was driven to Fresnes.

2

On 29 November he was taken to DST headquarters and before the Commissaire de Police, René Gouillaud, he was charged with having had ‘intelligence with the enemy’, for which the punishment was death. Twelve months later, he was still awaiting trial.

My affair will have to come to an end and I will have to be released. I have many great projects to do and many good things in store. Perhaps we could just pack our bags and go to that little corner and breed ducks. I send you kisses and caresses.

3

France was still divided, suspicious, resentful and in the mood for revenge. Behind their flinty walls, the prisoners of Fresnes knew very little about the political currents that were flowing around them. This man in particular, isolated in his little cell, was drifting unaware towards the centre of a storm that threatened relations between Britain and France. The

entente cordiale

was being chilled to the bone. But Déricourt knew nothing of that, he was no more in control of his ‘affair’ than he was in control of Jeannot’s nerves. His fate was being shaped by stealth, by the silently grinding wheels of an organization far beyond the reach of the DST. Behind his presence in Fresnes lay an extraordinary history of intrigue and deception within the British secret services.

Who was Déricourt and how had he come to be at the centre of that storm? The man whom an officer in the DST once described as the ‘French kid glove over the hand of Albion’

4

was the subject of a vivid array of stories.

…the son of a respected French family related to nobility. At the Lycée he excelled in mathematics and

science and set his heart on becoming an aviator. He was trained as a civil airline pilot and in 1933, at the age of 24, held the post of captain-pilot with Air France.

5

…he had worked during the 1930s as a trapeze artiste in Germany, there he made contact with a number of useful people…

6

…he had been to America on secret business, having escaped from France by crossing the Pyrenees…

7

There was only one consistent theme in Déricourt’s own account of his background: he never told anyone the truth about it. Once he had escaped his roots, he proceeded to bury them thoroughly. He cultivated a vaguely romantic air about his home and family and when pressed about his origins he would feign a pained silence, glance away and whisper ‘Château Thierry’. It was terribly effective.

Henri Eugène Alfred Déricourt was born at twelve-thirty in the morning of 2 September 1909, in the little hamlet of Coulognes-en-Tardenois, near Reims in the département of Aisne, some 100 kilometres north-east of Paris. South of the fields of Picardy the country rolls gently between the rivers Aisne and Vesle before running into the industrial outskirts of Reims. It is country that has periodically seen the arrival and departure of foreign invaders since the time of Julius Caesar, and they would come twice more during Henri’s lifetime.

The tiny community into which Déricourt was born worked under the feudal patronage of the local aristocracy. His father, Alfred, had been a peasant labourer until a stroke forced him off the land and into the Post Office. His mother, Georgette, was a domestic servant most of her life and worked as a concierge on the Thierry estates. Henri was the youngest of three boys. The eldest, Felix, was an ebonist – a craftsman skilled in working thin ebony

veneers into cabinets or tables. Marcel, the second son, became a decorator.