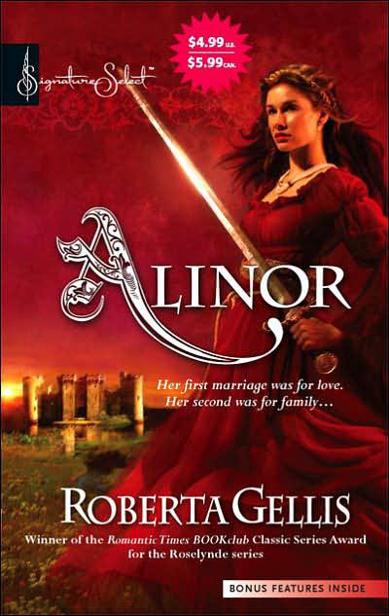

Alinor

Authors: Roberta Gellis

Alinor (The Roselynde Chronicles Book 2) by Roberta Gellis

She Lived In the Sweet, Restless Torture of a Smoldering Love...

In the year since her husband's death, Lady Alinor Lemange had felt too alone and frightened to think of herself as a woman. But from the moment darly sensual Ian de Vipont entered her life, she bacame aware of her long starvation. Trapped in a maze of trecherous power plays and volatile liaisonss, Alinor found herslef irresitibly drawn to the fine young knight with violence ans passion lurking in his black eyes. Amid the bloody battlegounds of France and England and the pageantry of the royal court, Alinor was willing to risk everything to save the intoxicating, breathless passion of the pan whose forbidden love promised her only pain and peril.

A LEISURE BOOK®

May 1994 Published by

Dorchester Publishing Co., Inc. 276 Fifth Avenue New York, NY 10001

Copyright © 1978 by Roberta Gellis and Book Creations Inc.

ISBN 0373837046

CHAPTER ONE

A lone knight in full armor spurred a tired, lathered horse up the winding road toward Roselynde Keep. That sight was so unusual in this year of our Lord 1206, the seventh year of the reign of King John—the accursed, as some called him—that the guard in the tower rubbed his eyes as if to clear his vision. Times had been bad periodically during the reign of King Richard because Richard did not love England, and the officers he appointed to rule and tax the land were often harsh. However, there was little lawlessness, and old Queen Alinor had been alive and had moderated any dangerous extremity in Richard's demands.

In 1199 Richard had been fatally wounded by an arrow at a siege he was conducting in one of the innumerable wars he waged. John, his youngest brother, the last of Henry Plantagenet's wild brood, had come to the throne. Although John actually loved England the best of all his possessions, he was driven by political necessity to even greater harshness than Richard and, to make all worse, he was a vicious man. Then, in 1204, the old queen died, and a strong force for balancing necessity against unreasonable taxation disappeared. The spite and exactions of the king then fell so heavily on so many that marauders prowled the land, and the roads were unsafe. In these days, men who had stitch or stick about them rode in armed groups.

Within the bounds of Roselynde's demesne, this was less true. Sir Simon Lemagne and his wife Lady Alinor had kept the peace on their own lands for a time, but Sir Simon had been stricken with a violent disorder of pains in the chest and arms more than a year past, and in late June he had died. Sir Giles had come from Iford when Sir Simon first fell sick, but his wife was not of the stuff of which Lady Alinor was made, and he had had to return to his own lands lest they fall into total disorder. Lord Ian had come also, but the king had summoned him away to the wars in Normandy. Beorn, Lady Alinor's master-at-arms, did what he could. There was still peace, although not what it had been in Sir Simon's time. Nonetheless, the guard knew that this knight did not come from the lands around Roselynde. It was plain from the state of his horse and his garments that he had ridden far and hard.

At the edge of the drawbridge, the knight pulled up his horse and shouted out his name. The guard's face lightened, and he called an order down the tower. The portcullis was raised as swiftly as possible; this was a welcome guest. The guard's surprise diminished when the knight said his troop followed and they should be passed when they arrived, but he still wondered what had brought his late lord's friend so far and in such haste that he outstripped his men. It was, however, no business of his to ask questions. He turned back to his duty of watching as the knight rode through the outer bailey, across the smaller drawbridge, and under the inner portcullis into the inner bailey.

Here a groom ran forward to take his horse, and a grizzled man-at-arms rose to his feet from a cask on which he had been sitting and watching two children, a girl of nine and a boy of seven, at play. The children looked up and tensed when they saw the true mail of a knight instead of the leather of a man-at-arms. Then they shrieked with joy and ran forward.

"Ian!" the boy cried.

The knight dismounted in one smooth movement, pushed off his helmet and shield, and bent to gather them to him, one in each arm. He kissed them both, then suddenly buried his face in the boy's hair and began to sob. The children, who had been wriggling with delight, quieted at once.

"Are you weeping because Papa is dead, Ian, or is there more bad news?" the girl, who was the elder, asked gravely.

Simon's daughter, Ian de Vipont thought, struggling to control himself. She is as like him as if she had no mother.

"Did you only just hear of it?" the boy asked. "It was in June. It is a shame you could not come to the funeral feast. Everyone enjoyed it greatly."

The boy stood quietly, his arms around Ian's neck, one small hand patting the knight's shoulder consolingly. His voice, however, was cheerful, irrepressible. In the midst of his tears, Ian choked on laughter. Alinor's son. Kind enough to wish to offer comfort but with a spirit that could not be quenched. He squeezed the children to him tightly once more, then stood upright and wiped his face with the leather inside of his steel-sewn gauntlet.

"No, no more bad news," he said to Joanna, and then, smiling on Adam, "I heard in July, but I was with the king in France besieging Montauban, and I could not get leave to come."

"Tell about the siege—tell!" the boy cried.

"Oh, yes, Ian, please tell," the girl begged.

The sun came out from behind a cloud, lighting green and gold flecks in the boy's hazel eyes and turning the girl's hair to flame. They were totally unlike in appearance, as if the mother's and father's strains were each so strong they could not be mixed; but that was only in coloring. Adam's hair was straight and black, his skin startlingly white, like his mother Alinor's, but his frame was sturdy and already very large for his age. That was his heritage from Simon, and a good heritage it was. It might be needful, Ian thought sadly, in the bitter times that loomed ahead, if King John did not mend his ways.

Ian had not known Simon when his hair was as red as Joanna's, but her eyes, a misty gray sometimes touched with blue, had cleared and brightened just as Simon's did when he was angry, eager, or happy. She was slighter than her brother but still sturdily made, no frail flower. No frail spirit either. The eager expression on Joanna's face mirrored that on Adam's.

"Did you scale the walls?" she asked.

"Did you burst through the gates?" Adam echoed.

"Master Adam! Lady Joanna!" the grizzled man-at-arms protested, "can you not see Lord Ian is dirty and tired? You shame our hospitality. A guest is bidden to wash and take his ease before being battered with questions."

"Beoth hal,

Beorn," Ian said in English.

"Beoth hal, eaorling,"

Beorn responded,

"wilcume, wilcume. Cumeth thu withinne."

Adam's eyes grew large. Beorn was an important man in his life. He taught the boy the fundamentals of sword and mace fighting. Adam could dimly remember that his father had started his lessons, but in the last year Simon had barely been able to come down to the bailey to watch and offer breathless and halting advice. Adam knew Beorn spoke a special language of his own. Adam could even understand some words, but Beorn would never address him in that tongue and would never permit him to speak it.

"Ian, Beorn answered you," the boy said.

The man-at-arms flushed slightly, and a faint frown appeared on Ian's brow. He made no comment, however, merely saying that it was time he went in and greeted their mother. After refusing the children's offer to accompany him and assuring them he would see them later, he strode into the forebuilding and mounted the stairs to the great hall, unlacing his mail hood and stripping off his gauntlets as he went. He looked up at the stair that led to the women's quarters, but he did not pause. Lady Alinor was as likely to be anywhere else in the keep as there, and he was sure someone had run ahead to announce his arrival.

In that supposition he was quite correct. Before he had crossed the hall to the great hearth, Lady Alinor came running from a wall chamber. She seized the hands he held out toward her and gripped them hard.

"Ian, Ian, I am glad at heart to see you."

"I could not come when I first heard. I begged the king to let me go, but he would not."

"You do not need to tell me that."

Suddenly her eyes were full of tears. She stepped forward and laid her head against his breast. Ian's hands came up to embrace her and then dropped. He fought another upsurge of his own grief. Alinor uttered a deep sigh and stepped back to look up at him.

"It is good to have you here," she said, only a trifle unsteadily. "How long can you stay?"

"I do not know," he replied, not meeting her eyes. "It depends on―"

"At least the night," she cried.

"Yes, of course, but―"

"Never mind the buts now. Oh, Ian, you look so tired."

"Our ship was blown off course. I meant to land at Roselynde, but we were blown all the way to Dover. We were attacked three times on the road. I could not believe it. In the worst days of Longchamp, things had not come to such a pass. I rode through the night. I had to―"

"You have bad news?" But Alinor did not pause for him to answer. "Do not tell me now," she said, half laughing but with a tremor in her voice. "Have you eaten?" He nodded. "Come, let me unarm you and bathe you." It was customary for the lady of the manor to bathe her guests, although Alinor had not usually done so for Ian.

"My squires are with the troop," he protested. "I rode ahead."

At that Alinor laughed more naturally. "I have not yet grown so feeble that I cannot lift a hauberk. Come." She drew him toward the wall chamber from which she had emerged. "The bath is ready. It will grow cold."

For one instant it seemed as if Ian would resist, and Alinor stopped to look at him questioningly. However, there was no particular expression on his face, and he was already following, so she said nothing. Something was wrong, Alinor knew. Ian had been her husband's squire before they were married. After their return from the Crusade, Simon had so successfully advanced his protégé's interests that Ian had been granted a defunct baronage that went with the estates Ian had inherited from his mother. He had been a close friend all through the years and a frequent visitor, particularly attached to the children. His fondness for them, coupled with his resistance to marriage had once made Alinor ask her husband whether Ian was tainted with King Richard's perversion. Simon had assured her that it was not so, that Ian was a fine young stallion, and he had warned her seriously not to tease the young man.

Alinor had been careful, because, despite being 30 years her senior—or, perhaps, because of it—Simon was no jealous husband. Indeed, until his illness, he had no cause to be jealous; he had kept Alinor fully occupied. Thus, when Simon warned her against flirting playfully with Ian, it was for Ian's sake. Alinor acknowledged the justice of that. It would be dreadful to attach Ian to her, dangerous, too. There was violence lurking behind the young man's hot brown eyes and, although Alinor had loved Simon and been content with him, she had never denied that Ian was a magnificent male animal who could be very attractive to her. Ian had been careful too, seldom touching Alinor, even to kiss her hand in courtesy.

Nonetheless, they had been good friends. Alinor knew when Ian was carrying a burden of trouble. Ordinarily, she would have pressed him with questions until he opened the evil package for her inspection. Alinor had never feared trouble. Simon had said sourly more than once that she ran with eager feet to meet it. That was because she had never found a trouble for which she or Simon or both of them together could not discover a solution. Trouble had been a challenge to be met head on, trampled over, or slyly circumvented— until Simon died. Now, all at once, there were too many troubles. Alinor could not, for the moment, muster the courage to ask for another.

The afternoon light flooded the antechamber with brightness, but the inner wall chamber was dim. Ian hesitated, and Alinor tugged at his hand, leading him safely around the large wooden tub that sat before the hearth. To the side was a low stool. Alinor pushed Ian toward it, grasping the tails of his hauberk as he passed her and lifting them so he would not sit on them. She unbelted his sword before he had even reached toward it, slipped off his surcoat, and laid it carefully on a chest at the side of the room. Ian gave up trying to be helpful and abandoned himself to Alinor's practiced ministrations, docilely doing as he was told and no more.

In a single skillful motion, Alinor pulled the hauberk over his head, turned it this way and that to see whether it needed the attention of the castle armorer, and laid it on the chest with the sword. Then she came around in front of him and unlaced his tunic and shirt. These were stiff with sweat and dirt, and she threw them on the floor. Next, she knelt to unfasten his shoes and cross garters, drew them off, untied his chausses, and bid him stand. Again Ian hesitated. Alinor thought how tired he was and was about to assure him he would feel better after he had bathed, but he stood before she could speak. Still kneeling, she pulled the chausses down and slipped them off his feet. When she raised her eyes to tell him to step into the tub, she saw the reason for his hesitation.