Algren (26 page)

Authors: Mary Wisniewski

Algren at a party at the home of Andy Austin, in about 1975. A

NDY

A

USTIN

C

OHEN, USED WITH HER PERMISSION

Algren's house in the old whaling community of Sag Harbor, New York, where he spent his last, happy months. M

ARY

W

ISNIEWSKI

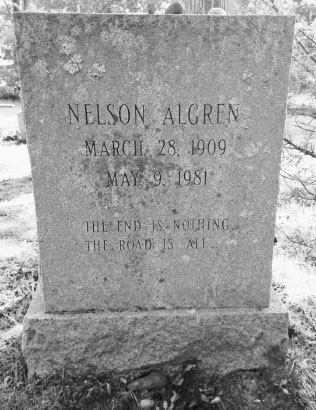

Algren's grave in the Oakland Cemetery in Sag Harbor, New York. On the grave is a quotation from Willa Cather: “The end is nothing / The road is all.” M

ARY

W

ISNIEWSKI

THE WALLS BEGIN TO CLOSE

Before long, you will see this curious thing: the speakers stoned from the platform and free speech strangled by hordes of furious men who in their secret hearts are still at one with these stoned speakersâbut who dare not say so.

âM

ARK

T

WAIN,

T

HE

M

YSTERIOUS

S

TRANGER AND

O

THER

S

TORIES

“Hooray for Hollywood”

âT

ITLE OF A SONG BY

R

ICHARD

W

HITING

If Nelson Algren's life were a roller coaster, the years 1949â1951 would be at the top of the Bobs at the old Riverview amusement park, with a grand view of the fairground. He had written one of the greatest novels in American literature, and was being recognized and celebrated for it in his own lifetime. He had a lovingâif long-distanceârelationship with one of the most remarkable women of the age. And he had enough money to buy what he had long been seekingâa home of his own. The years after 1951 saw a falloff personally and creativelyâcaused by things sometimes in his control, sometimes not. His troubles were brought on by a

fearful government that had forgotten its own principles, Hollywood greed, and critics so dazzled by their own theories that they forgot to value what Joseph Conrad called “the things of the earth.” Nelson was also hurt by large measures of his own arrogance, insecurity, and foolishness, along with the fatigue that comes from a long struggle and plain bad luck. That doesn't mean he did not write brilliant, prophetic social and literary criticism, or that he did not have romances and friendships in his next thirty years. He also wrote another good and influential novel,

A Walk on the Wild Side

. But by 1952 his best work was behind him.

Fortunately, nobody knows his own future, and Nelson started the 1950s with optimismâhe wanted to try his luck in Hollywood, and he wanted to buy his own place in the Indiana Dunes in Miller Beach, near his old neighbors from Bronzeville, Neal and Chris Rowland, and Dave Peltz from the WPA. The two quests were relatedâdespite the strong sales for

The Man with the Golden Arm

and $1,500 from the Book Find Club, Nelson was not making much money because he had already been paid two years of advances from Doubleday, and he hoped the Hollywood money could buy him his house.

Miller is a neighborhood of Gary, Indiana, and was a magnet for bohemian types and Chicago Jews looking for a lakeside escape from the city's hot, humid summers. It was not a fancy lakeside suburbâChicago's wealthy had homes north of the city in Kenilworth and Winnetka, and went to lakefront resorts in the “Harbor Country” of southwestern Michigan. Miller was mostly middle class, with humble ranch houses set in widely spaced lots and a compromised view that combined blue lake with gray steel mills, their smokestacks shooting orange plumes of fire into the night sky. But it was affordable and convenient to the city by means of the South Shore electric train. Nelson's plan was to keep the Wabansia flat for weekends in the city, but live in Miller during the week. Bernice's

lake house had been in the area, but had been given up during her illness and later destroyed when the steel mills expanded. Now Nelson hoped to re-create the peace he had found as a visitor at both Bernice's cottage and as a guest of the Rowlands'âa quiet place where he could swim in the lake and take walks in the dunes when he was not reading and writing. He had motherly Chris Rowland look out for a place for him while he worked on a movie deal.

In the fall of 1949, film noir producer Bob Roberts, who had formed an independent production company with actor John Garfield, reached out to Nelson about a movie version of

Golden Arm

. Like Algren, Garfield was an urban Jew who had spent time riding the rails and picking fruit during the early 1930s. Known for playing tough, working-class heroes, Garfield had been nominated for a best actor Oscar for the great 1947 boxing movie

Body and Soul

, which Roberts had produced. Roberts and Garfield also had worked together on

Force of Evil

in 1948, about a numbers racket. The unconventionally handsome realist actor seemed perfect for Frankie Machine, but Nelson wondered to Ken McCormick if he had enough money to buy him. There were some red flags about the Garfield-Roberts companyâGarfield had backed out of a deal in late 1946 to base a movie on the life story of Chicago boxer Barney Ross once it came out that Ross had suffered from morphine addiction. The 1947 classic

Body and Soul

contained some of the features of Ross's life, but without the drug problem. Ross sued, and the lawsuit eventually settled for $60,000. Simone supported putting Frankie on the big screen, but questioned Nelson's business sense, and warned him to have a contract in hand

before

he went out to Los Angeles. Madeleine Brennan had found Nelson a West Coast agent named Irving Lazar, and wanted to get a deal that would give Nelson a cut of the box office receipts. By mid-November nothing was set, and Brennan and a lawyer had to disabuse Roberts of his mistaken notion that a sale had been made. So Nelson had no

formal contract when he and a former drug user named Ken Acker, who was riding along as a technical assistant, escaped part of the bleak Chicago winter on the luxurious Super Chief train, riding through deserts and mountains. Nelson was told that no one else was bidding for the book at the timeâthe narcotics angle made it a tough sell. The Motion Picture Association of America's production code specified that neither illegal drug traffic nor drug addiction could be shown on the screen.

Out in Hollywood Nelson got to see Amanda again, and found her looking fine, stylish and saucy enough to heckle Roberts during a meeting in Garfield's suite at the Chateau Marmont, a white, faux Gothic castle overlooking Sunset Boulevard. She had been working on herselfâtaking dance classes to learn the tango and the rumba, having her nails done, making her own stylish clothes and spending her savings on a therapist. She had never married that photographer. Amanda cheered up Nelson, who was not feeling too sure of himself in Los Angeles, which he later described as a “flying saucer” and the “Land of Hollow Laughter” to which no one could really belong. The sun-drenched city with its palm trees and slim, suntanned people seemed unreal compared to Chicagoâlike a shiny oasis that vanished when you got too close. “Everybody here is a millionaire and everything is love. Everything is a ball, nobody works, nobody talks about anything but money,” he wrote Jack on Chateau Marmont stationery. Nelson was getting the “Ten-Day-Hollywood-Hospitality Treatment,” which he decided later was designed to get writers from the hinterland to be so grateful they would sign anything. Garfield's place had been stocked with cases of liquor of diminishing qualityâgood scotch, fair rye, and cheap bourbon, but no gin, which was Algren's favorite. Nelson joked that Bob Roberts even dangled the prospect of meeting his old favorite actress Sylvia Sidney, and Nelson bowed in her direction, though it turned out she was in Brussels. Garfield eventually showed up

from his trip out east. Between tennis matches, he praised Frankie Machine. Roberts took Algren to dinner at the elegant Romanoff's, a favorite spot for movie stars that was run by a phony Russian noble. Nelson worried that the hospitality was phony, too, and that he would eventually be asked to pick up part of the bill for his stay himself. This turned out to be trueâRoberts knew no one else was after the book and drove a hard bargain. Nelson hired a new agent, George Willner, and demanded 5 percent. During a separate trip out west later in the spring, they hammered out an agreement that would pay Nelson $5,000 for the option, another $10,000 if Bob picked it up, and $4,000 for Nelson to write the script, 5 percent if the movie was made or 50 percent of the sale price if the rights were sold. The deal was not going to make him a millionaire right away, but it was better than the pay from writing book reviews and royalties on the upcoming French and Italian editions of

Never Come Morning

. And it would let him buy his house.

In between his trips to the West Coast Babylon, Nelson got to fly to New York City to be awarded the first ever National Book Award for fiction at the Waldorf-Astoria. He had to wear a tuxedo for the first and only time at the March 16 ceremonyâhe did not wear one for any of his weddings. David Dempsey of the

New York Times

claimed that a correspondent for the defunct

Hobo News

was in attendance, complaining of Nelson's betrayal of his proletarian principles: “Just for a handful of silver he left us / Just for a riband to stick on his coat.” Giggling over newspaper photographs of the ceremony back in Paris, Simone, Jacques Bost, and Jean-Paul Sartre all thought that Nelson's outfit made him look like the silent screen comedian Harold Lloyd. Also winning that night were William Carlos Williams for poetry and Ralph Rusk for his biography of Ralph Waldo Emerson. The great Eleanor Roosevelt was there, with her warm, toothy smile, to give Nelson his award and embrace him. He joked in his acceptance speech that he might have to pawn the

award somedayâbut in the newspaper photos he is smiling boyishly and without cynicism. Ken McCormick at Doubleday was thrilled with the publicity the prestigious award would give

Golden Arm

. Doubleday was $5,000 over budget in spending on advertising for the book, but McCormick said this was done with their eyes open, because it was such a privilege to publish Algren's wonderful book.

Nelson also was working on a new projectâin late 1948 he had met the gifted photographer Art Shay, younger than Nelson by thirteen years, with sharp, dark eyes, a wide, round-cheeked face, and a build like a bulldog. Shay was a tough guy, a self-described “pushy Jew” who had been brought up in the Bronx and flown over fifty bomber missions in World War II. A reporter for

Life

who had decided to go freelance as a photographer, Shay had become a fan of Algren's stories and wanted to do a picture essay about him for a big, eight-page

Life

magazine spread. The story would showcase Nelson with some real-life models from his booksâthe denizens of Madison, Division, and Clark Streets. It would have been great publicity had it worked outâ“it was a pretty good pegâhe had just won the book award,” Shay remembered ruefully.

When Art arrived at Nelson's Wabansia apartment with his Leica, he found the great writer in a khaki-colored undershirt boiling water for tea on his oil stove. “You don't want me to get the dirty dishes out of the sink, do you?” Nelson wondered, wanting to be helpful. Art had a list of the streets he wanted to visit, and they went out to see Nelson's “night people.” Nelson almost never seemed to notice that he was being photographed, which made him a good model. He always appears in Shay's photographs as a mild-mannered, bespectacled observer, dressed in an old army medic's jacket, sometimes with a cigaretteâas unobtrusive as a ghost that only the camera can see. In one photo Nelson is taking coffee among the other bums at the Pacific Garden Mission south of the Loop, where a large painted legend on the wall affirms that Christ Died for Our Sins. In others

he studies the racing form at the Hawthorne track, picking a string of losers; or he watches the smiling waiters at an all-night restaurant on Clark Street hustle out a drunk who'd fallen asleep at his table. The only time Nelson looks tense and uncomfortable is when Art took a picture of him with an East St. Louis friend who was demonstrating how to shoot heroin. “Bad idea,” Nelson told Art afterward. “He's been off it a while. Posing got him too excited.” Fortunately, the man stayed clean. Sometimes, after a long Saturday night of taking in the scene, Art and Nelson would go to Goldie's cluttered Lawrence Avenue apartment for breakfast.