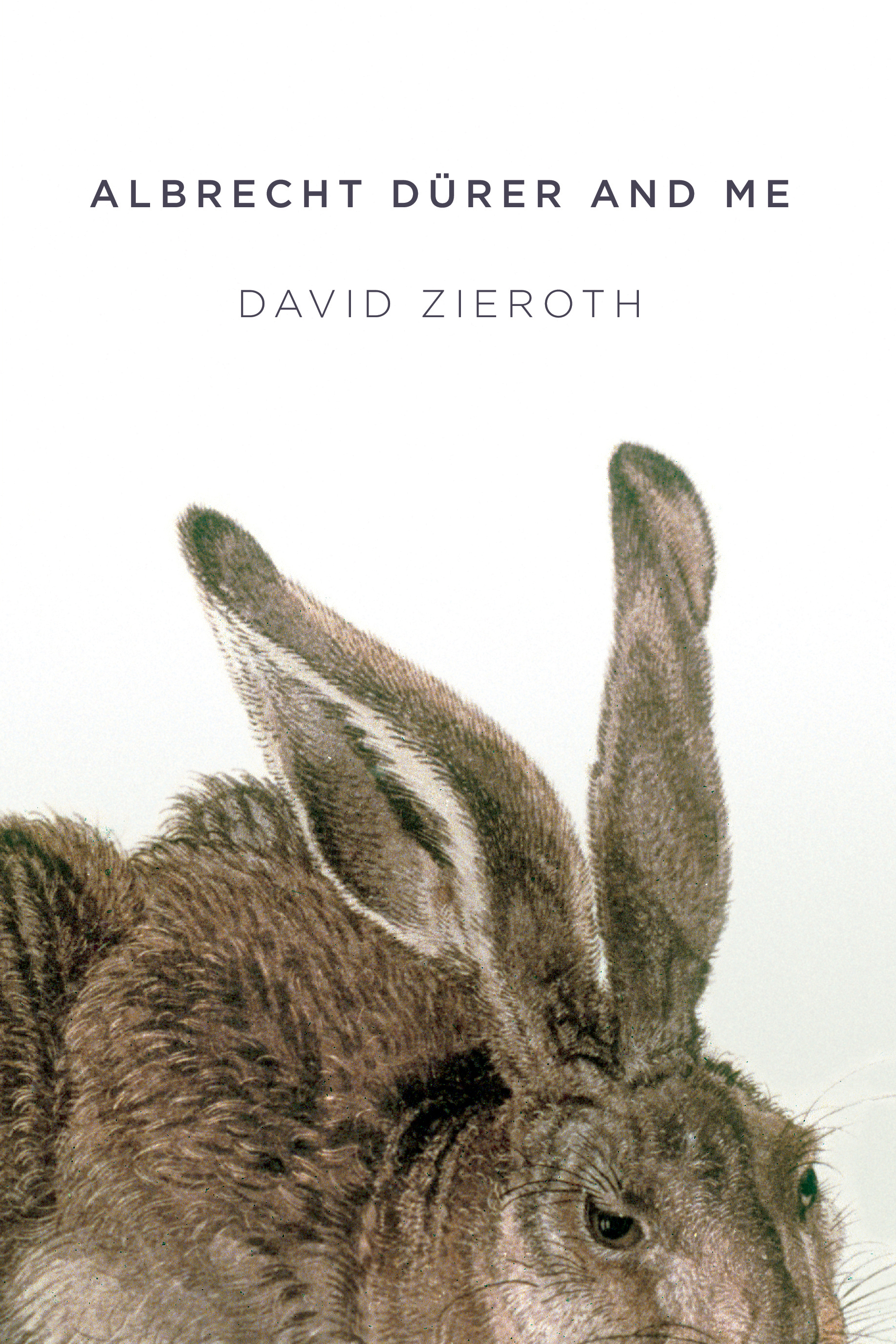

Albrecht Dürer and me

Albrecht Dürer and me

Albrecht Dürer and me

David Zieroth

Copyright © 2014 David Zieroth

1 2 3 4 5 â 18 17 16 15 14

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without prior permission of the publisher or, in the case of photocopying or other reprographic copying, a licence from Access Copyright, www.accesscopy right.ca, 1-800-893-5777, [email protected].

Harbour Publishing Co. Ltd.

P.O. Box 219, Madeira Park, BC, V0N 2H0

www.harbourpublishing.com

Edited by Silas White

Cover design by Shed Simas

Text design by Carleton Wilson

Printed and bound in Canada

Harbour Publishing acknowledges financial support from the Government of Canada through the Canada Book Fund and the Canada Council for the Arts, and from the Province of British Columbia through the BC Arts Council and the Book Publishing Tax Credit.

Cataloguing data available from Library and Archives Canada

isbn

978-1-55017-674-2 (paper)

isbn

978-1-55017-675-9 (ebook)

For those who called me away, and for those who called me back

Nothing, above all, is comparable to the new life that a reflective person experiences when he observes a new country. Though I am still always myself, I believe I have changed to the very marrow of my bones.

â from

Italian Journey

by Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, translated by W. H. Auden and Elizabeth Mayer

dislocation

Viennese shoes

in Wien, even the homeless wear good shoes

or at least one bedraggled, bearded, filthy-

coated giant managed uncommonly decent leather

brogues that toe-curl a bit, an Italian smile

intimating heat and lust and care for craft

yes, any change of place forces up generalizations

rife and ready, and even knowing how quickly

scenes arise in the mind: lithe men, short hair

long strides, briefcases, or young artists debating

over Styrian beer and new wine spritzers the edge

of mathematical, abstract space â I know really

very little: glittering steel lines of the tram

on Ungargasse, straight under my feet

and along some sections, short grass snuggles

green against silver â earth and engineering

power-sharing â what could either say to the other

about times when heels of famous men

clacked these cobblestones: Freud's boots, how he

slipped into leather smoothly pleased with strength,

and Hitler's shoes, paint bespattered, then further back

and further back again until an Ottoman stands

outside the ringed wall of the city, 300 cannon strong

the story goes, Grand Vizier Pasha tapping

his magnificent Asian slippers on these stones

passport . . .

inspected and stamped, leads to

towers and gargoyles â and cafés

the ruined faces of fathers

wide, haughty mouths of mothers

their children oblivious

except to couples

kissing on stone bridges

an old man crossing himself

as he bicycles past a cathedral

document made to bend

though not in the eyes of the law

a young woman looks at me

frankly, then waves me on

to empty my pockets, remove

my belt and pass beep-free

through their ultra-machine

these open-faced beings

the way they gaze

the pale madonnas awaiting me

lean to the left, ear touching

the baby's head, he so finely

detailed, as if Florentine artists

wanted to paint more of their power

into him than into her:

his divine versus her blessed

how her near-blandness recalls

the manner of those calm guards!

upright in blue shirts

watching at entryways

a touch of knowledge

dusting their cheeks

train ride

passing through Linz I notice trains

preternaturally, not the cylinders

for carrying acid chemicals

graffiti on their bulging sides

but older blocky types

of faded wood now silenced

on a weedy siding, while I sit in the upper

section, aware of speed and efficiency

across from me two young men gaze

into a camera steadied by the über-clean

hands of the blond one, occasionally

speaking quiet German phrases

while the old man cross-aisle snorts

as he sleeps though his jaw remains firm

and never once does his mouth fall slack

to reveal a vacuity no one has to see

while

I

see how I've travelled beyond

the two paragons but haven't yet arrived

at the one who catches his escaping breath

though I also note he's mastered not

sliding on his seat into a heap of age

I turn away from humans close at hand

to look again at boxcars and wonder

what they were filled with, carried

and left behind: routine stuff of light

bulbs and oddments from elsewhere

tractor parts and toiletries, nothing worse

can be imagined today as our train passes

through Linz, bearing me, grateful for

considerate and sleeping companions, easy

to say now we're going somewhere safe

travelling without earplugs

spotted cows on pasture slopes

moo where upper alpine snow

leaks into June-fed creeks constrained

in narrow rock walls, each unmoved

by burgeoning white

when evening arrives, all noises

cease here in my

pension

except for one: someone's

far-off singing, perceptible

only when other sounds

subside, its pitch insisting

my tired mind identify

and end its

e-e-e

at once

and failing to do so

I resort to pillow-wrapping

my head, to await any dream

wherein I escape that timbre

not unlike the one (I begin to think)

we hear just before dying: such

thoughts entangle the traveller

unwisely travelling earplug-less

and who is vexed to discover

next morning the mosquito buzz

arises from the radio at his bedside

an opera-broadcasting station

not turned completely off

as if the previous person here

had been malignly planning ahead

to effect another's discomfort

and thus he suffers because he assumes

he can never correct creation

believing glumly the arrow

of the irreparable always aims for him

yet in the cool of the next dawn

he's enchanted to encounter birds

new to him singing in Italian

on the occasion of visiting Auden's grave

somehow I don't expect sighing evergreens

or cruel April's birds tuning up their notes

or the autobahn's whine beyond the church's

sweet-cream-pastry-coloured plaster walls

though I recognize the iron cross and plaque

labelling the deceased as poet and man of letters

and somehow the ivy's dense entanglement

surprises me as do wilting winter pansies

on top of the small rectangle of the plot itself

(how can it hold such long, grand bones?)

and a two-pence copper coin lying atop moss

that says he is loved by someone from home

and those admirers from other lands (like me)

know better than to swipe this little token

even as I feel its melancholic foreignness

enter my thumb and vibrate with an eagerness

to claim the wrinkled poet as my own

yes, I know how men slide daily under earth

and what remains of them upside stays briefly

before it too leaves like wind or highway noise

while calamity clots nearby, one hamlet away

even as that woman in her red coat crosses

a green field, happy black terrier leaping up

to her hand, as a crow settles his wings on pale

winter stubble, and an old man in a crushed hat

posts a letter at a yellow box â and may a reply

come sooner than he expects from a grandson

he loves to praise as only a free man can praise

but likely it's a bill, what must be paid

in a certain period before penalties apply

and debts accrue and demands mount

and a day passes in which he fails to relish

this heaven-side of grass, neglects the glory

in birdsong! â and in men whose songs rise

so smoothly from their natures we forget

how both ease and fine form came to pass

out of a morning's work in the low house

with green decorative siding not far from

his grave, a domicile easy to pass by without

a murmur of wonder â though the German words

under his photo leave me squinting, envious

of those who know more than I, who knew him

as a neighbour, summer visitor to Kirchstetten

on a back road bordered by willows ready to bud

from soggy forest floor with leaves faint for now

in Duino

narrow roads off the autobahn

offer tour buses no place to park

should passengers want

to see where Rilke slept

Princess della Torre e Tasso's gilded

family portraits of past aristocrats

staring down, uncomprehending

I step onto a balcony overlooking

the Gulf of Trieste, notice no angels

though commercial oyster beds

at the mouth of the Isonzo River

provide a symmetry the poet

may have admired from his cliff path

I am thinking a trace of gravitas

might remain on this stone

balustrade he may have touched

(or pounded) and where

in three languages is written

on its limestone lip the command

not to lean over, which I heed

Apollo beams down to warm

my thoughts again, so once more

I wonder how the poet saw from here

âwind full of cosmic space'

what remains for me white cliffs

and blue sea, curve of the gulf

and sunlight calling one wave

to appear just as another dips and

disappears without any âendlessly

anxious hands' framing

what cannot so easily pass away