Al-Qaeda (52 page)

Authors: Jason Burke

27. A small number of experienced Moroccan militants – part of the post-Afghanistan al- Qaeda diaspora – were able to recruit at least twenty suicide bombers with ease in the slums of Casablanca. They killed fourteen people with an amateurish attack in the city in May 2003.

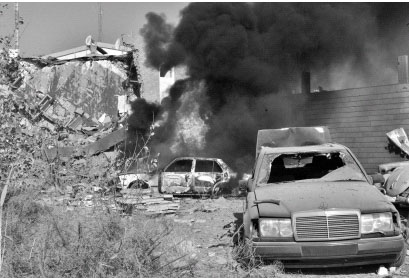

28. An unprecedented alliance between former Ba’athists, who supplied safehouses and matériel, and jihadis, who supplied willing suicide bombers, led to an extremely effective bombing campaign designed to cripple coalition attempts to stabilize Iraq. This attack in Baghdad in 2003 forced the United Nations to pull out.

29. Attacks on synagogues, the British consulate and a British-owned bank in Istanbul were the work of a local cell recruited by Turkish graduates of the Afghan training camps.

30. The bombings of trains in Madrid in March 2004 showed the future of Islamic militancy – fragmented, autonomous cells executing independent attacks, sometimes for propaganda purposes in the Islamic world, sometimes merely to cause fear and destruction.

31. Bin Laden’s greatest achievement has been spreading the ‘al-Qaeda’ ideology. Islamic militants are now heroes to millions of Palestinians, such as this crowd at a funeral for a dead activist in Gaza, and to many Muslims worldwide.

32. The hunt for Islamic militants often relies on allies who may in fact be part of the problem. Pakistan has been a breeding ground for militancy for decades, as much because of profound social inequality and overseas interference as any government policy. Here a suspected militant is being arrested by a Pakistani soldier in Waziristan, March 2004.

Conclusion

The sun came up as we drove across the open grasslands north of Kandahar. Trains of camels threw their long shadows across the dessicated earth. Thin strands of smoke rose from the domed mud roofs above the tightly clustered villages. An occasional water course, though now dry, was marked nonetheless by trees, a patch of incongruously green grass, a stand of tough little bushes. The mountains on the eastern horizon were a monumental barrier of dusty brown jagged peaks sharp beneath the pale early morning sky.

You could drive from Kandahar to Kabul in four hours in the summer of 2006 and, on the slick restored tarmac, it was a far more comfortable journey than it had been eight years earlier, when I had driven the road in the opposite direction on the eve of ‘Operation Infinite Reach’, the American missile strikes against the training camps around Khost after the bombings in east Africa. But then, though the trip took between sixteen and twenty hours of driving, there was little personal risk to a Western journalist. Now burned wrecks of vehicles, victims of Taliban ambushes, lined the roadside. In places, the surface had been scarred by improvized bombs, made with techniques honed in Iraq. The contrast was marked.

Having left the south and east of Afghanistan without serious development funds, a real government or even much in the way of a military presence for over four years, the Western coalition was now in trouble. The Taliban, offering a rough justice, a degree of security, sometimes a meagre salary, had flowed back into the areas they had been forced out of in 2001. From their rear bases over the Pakistani border, a rough alliance of tribal and religious leaders, drug traffickers and jihadi

militants, boosted by large numbers of disillusioned and desperately poor villagers, had taken control of vast parts of the eastern and southern provinces. It was, by the summer of 2006, impossible even to travel to Sangesar, the village less than an hour outside Kandahar where the Taliban had been formed in 1994 and where I had interviewed locals a year or so before. Back then the window of opportunity opened up by the war of 2001 had been closing. Now it had shut.

There were many reasons for the failure in the south of Afghanistan. Too much political will and attention had been focused on Kabul, the north and the west, most of which remained relatively stable and prosperous. The money spent in Afghanistan, always inadequate, had too often been wasted on American subcontractors, on badly conceived projects in the wrong place, or on the wrong people. Internal battles had not helped either. Opium production was prodigious, partly as a result of the bitter row over eradication strategy between the Europeans, who favoured long-term development, and the Americans, who favoured short-term coercion. As I watched the Kabul nouveau riche promenading around a lake on the outskirts of the city, where cans of beer were openly on sale, or listened to the braying Western experts in the newly constructed five-star Serena Hotel in the centre of Kabul or marvelled at the soldiers and diplomats behind their treble walls of blast blocks, steel and barbed wire, it was difficult to be too optimistic about the country’s future, at least in the short term. And then of course there was the fruitless hunt for bin Laden.

1

At first glance, and at the time of writing, bin Laden’s position looked weak. Though his exact location was unknown he was likely to be hiding among the Pashtun tribes along the mountainous Afghan–Pakistani frontier south of Khost and north of the Pakistani city of Quetta in the tribal agency of Waziristan. He was last seen in Jalalabad on 14 November 2001, a day or so before the Taliban evacuated the city. He has not made a public appearance since.

2

But, in fact, the war is not going badly from bin Laden’s point of view. On 27 December 2001, even as everything he had built over the preceding five and a half years appeared to be collapsing around him, bin Laden issued a confident call to arms. ‘Regardless if Osama is killed or survives,’ he

said, ‘the awakening has started, praise be to God’.

3

Sadly, as events in London and elsewhere have shown, he was right.

Bin Laden has always aimed to radicalize and mobilize those Muslims who have shunned his summons to action. This has been the main objective and the critical problem for radical Islamic activists for three decades and more. Bin Laden’s sponsorship of terrorist attacks has always been a means to an end, with the destruction of life and property merely a useful bonus. The main consideration has always been proving that there is a cosmic battle between good and evil underway and that Islam, and thus all that is good and righteous and just, is in desperate peril. Once the umma are convinced of this, bin Laden thinks, the world’s Muslims will rise up, return to the true path and, having thus earned the blessing of God, cast off the shackles that have been laid upon them over centuries of ‘humiliation and contempt’. Their struggle, which will be a violent one, will be rewarded with victory.

That agitation is the primary task of the activist is recognized by most senior militants. Abu Musab al-Zarqawi, writing six months before he was killed in an American air strike, wrote that ‘in this jihad we have to feed the media so as to reveal the truth, inspire the will to act, to develop the collective consciousness… the sword and the plume complement one another’. In a document called ‘Mending the Hearts of the Believers’, published on the internet in late 2002, ‘Salem al-Makki’ applauds ‘the success of the call by the Sheikh Osama bin Laden and the al-Qaeda organization to ignite the contact-line throughout the world between the… heroes of the Muslim nation and the blessed vanguard force… and the Jewish-Christian coalition that controls Muslim holy sites and their natural resources.’ Al-Makki says that bin Laden and his aides have ‘accentuated the level of consciousness of the [Islamic] nation’s youth’ and that, as a result, the ‘annihilation of al-Qaeda has become an impossible task’. The strength of al-Qaeda, al-Makki says, lies in its success ‘in exporting its deep-rooted worldview… so that it has become like a currency used everywhere within the nation’.

4

If bin Laden’s aim – and that of other militants – is to radicalize

and mobilize then one would imagine that the aim of those running the War on Terror would be to counter those efforts. A swift survey of popular newspapers in the Islamic world (and beyond) or of Friday sermons in the Middle East’s mosques or a few hours spent in a bazaar or a souk or a coffee shop or kebab restaurant in Damascus, Kabul, Karachi, Cairo, Casablanca or indeed in London or New York, shows clearly whose efforts are meeting with greater success. Bin Laden is winning.

5

The sad truth is that the world is a far more radicalized place now than it was prior to 11 September. Helped by a powerful surge of anti-Americanism, Washington’s incredible failure to stem the haemorrhaging of support and sympathy, and by modern communications, the language of bin Laden and his concept of the cosmic struggle has now spread among tens of millions of people, particularly the young and angry, around the world. It informs their views and, increasingly, their actions. In Indonesia in November 2002, days after the Bali bombing, I saw young Islamic activists wearing bin Laden T-shirts. There were pro-Palestinian slogans on many walls in Jakarta. Hundreds of thousands of young men log onto to jihadi websites across the world each day. Once the anger and resentment of young men and women throughout the Islamic world was voiced in the language of relatively moderate political Islamists. Now the slogans are very often those of bin Laden, al-Zawahiri, al-Zarqawi and the other public ideologues of the most radical extreme of modern militancy. On a visit to Kashmir in November 2003 I was surprised and concerned to hear a Muslim doctor in a town in one of the most violent areas talking about the Crusader–Zionist–Hindu alliance. This particular local bastardization of the standard jihadi worldview, predicated on a Western/Christian/Jewish conspiracy to dominate Islam, struck me as a particularly tragic example of how the radicals’ debased discourse is now so prevalent. For centuries Kashmir was known for its tolerant, pluralist, moderate, mystic and syncretic form of Islamic observance. In these harsh times, it seems, ‘soft’ Islam is easily pushed aside by newer, ‘harder’ strands. The brand of activism, articulated in Islamic terms and justified by reference to the Islamic tradition, that is personified by bin Laden, is fast becoming a global discourse of dissent. Al-Makki, with his talk of

al-Qaeda-style radicalism as the ‘common currency’ of the Islamic world, was barely exaggerating.