AK-47: The Weapon that Changed the Face of War (32 page)

Read AK-47: The Weapon that Changed the Face of War Online

Authors: Larry Kahaner

BOOK: AK-47: The Weapon that Changed the Face of War

13.22Mb size Format: txt, pdf, ePub

The fact that AKs enjoyed an antiestablishment cachet would help sales of products aimed at youths and those who liked to think of themselves as outside the mainstream. Harley-Davidson had successfully fostered an outlaw biker patina even though most Harley riders were males over forty, who had wives and children and enjoyed high family incomes from straitlaced jobs. For masculine sports and camping gear, the Kalashnikov name probably could move products if the marketer was skillful. “The articles are very similar to my rifle,” Kalashnikov said. “Reliable, easy to use, and indestructible.”

The announcement was met with great fanfare and media attention, but nothing ever became of the scheme. The company simply disappeared, and once again Kalashnikov failed to make money on his invention.

Still, the AK mystique grew stronger.

Playboy

magazine in 2004 listed the AK-47 as number four in its feature “50 Products That Changed the World: A Countdown of the Most Innovative Consumer Products of the Past Half Century.” That the AK was considered a consumer item, behind the Apple Macintosh desktop computer (number one), the Pill (number two), and the Sony Betamax VCR (number three), was a true indication of the gun’s seminal and long-lasting effect on the modern world. Citing a July 1999 State Department report mentioning the weapon,

Playboy

’s editors noted, “In some countries it is easier and cheaper to buy an AK-47 than to attend a movie or provide a decent meal.” The magazine also cited a

Los Angeles Times

article calling the gun “history’s most widely distributed piece of killing machinery.”

Playboy

magazine in 2004 listed the AK-47 as number four in its feature “50 Products That Changed the World: A Countdown of the Most Innovative Consumer Products of the Past Half Century.” That the AK was considered a consumer item, behind the Apple Macintosh desktop computer (number one), the Pill (number two), and the Sony Betamax VCR (number three), was a true indication of the gun’s seminal and long-lasting effect on the modern world. Citing a July 1999 State Department report mentioning the weapon,

Playboy

’s editors noted, “In some countries it is easier and cheaper to buy an AK-47 than to attend a movie or provide a decent meal.” The magazine also cited a

Los Angeles Times

article calling the gun “history’s most widely distributed piece of killing machinery.”

Amid the AK hype, museums began looking at the rifle’s effect on civilization and culture in a more somber and thoughtful way. The Dutch Army Museum in 2003 and 2004 hosted an exhibit on the AK called

Kalashnikov: Rifle without Borders

that offered visitors a look at multimedia displays on wars in which the rifle had played a deciding role. It showed combat children holding AKs in Africa and elsewhere. One exhibit dramatically illustrated the weapon’s destructive ability by showing a bullet pattern in a porous block. However, even a serious museum could not ignore the Kalashnikov’s pop culture side: attendees saw AKs that had been chrome-plated; others were covered with hot pink fabric and glitter. Even a military-oriented museum could not escape the fact that AKs had become so ingrained in world culture that people adorned them with bright colors, perhaps to defuse some of their power. Kalashnikov himself opened the exhibit amid fanfare. Again, as he had done at every public opportunity in the past, he used the forum to blame politicians for misusing his invention and to absolve himself of the AK’s terrible legacy.

Kalashnikov: Rifle without Borders

that offered visitors a look at multimedia displays on wars in which the rifle had played a deciding role. It showed combat children holding AKs in Africa and elsewhere. One exhibit dramatically illustrated the weapon’s destructive ability by showing a bullet pattern in a porous block. However, even a serious museum could not ignore the Kalashnikov’s pop culture side: attendees saw AKs that had been chrome-plated; others were covered with hot pink fabric and glitter. Even a military-oriented museum could not escape the fact that AKs had become so ingrained in world culture that people adorned them with bright colors, perhaps to defuse some of their power. Kalashnikov himself opened the exhibit amid fanfare. Again, as he had done at every public opportunity in the past, he used the forum to blame politicians for misusing his invention and to absolve himself of the AK’s terrible legacy.

At home, his countrymen were preparing to honor their most famous inventor, too. In 1996, construction of a Kalashnikov museum in Izhevsk began but was suspended due to insufficient funding. With pleas for money throughout Russia and on the Internet, the $8 million Kalashnikov Weapons Museum and Exhibition Center opened on the arms maker’s eighty-fifth birthday in 2004. The museum was designed not only to honor Kalashnikov’s work, but also to jump-start the decaying city of Izhevsk, a boom-town during World War II and the cold war years, now fallen on hard times. Isolated and far from much of Russia’s commerce, the city existed for the production of arms, which it made at the rate of more than ten thousand a day during World War II. Later during the cold war it continued to produce weapons, mainly AKs in great numbers, providing employment and prosperity.

Since the fall of the Soviet Union, with no more AKs being made, Izhevsk officials hoped that the museum would attract tourists. In what was once a top-secret location, closed to outsiders and casual tourists alike, city officials were hoping for urban renewal and better times based on the AK’s star power. During speeches, the mayor conveyed that the museum embodied the strength of the city in that it produced a dependable product, one that worked reliably and was revered worldwide. Like commercial marketers hoping to make money off of Kalashnikov by selling consumer items with his name and endorsement, his adopted town was relying on his celebrity status, too, to help jump-start its economy.

So far, the results have been lukewarm.

PERHAPS THE INVENTOR’S GREATEST chance at financial success came in 2003, when British entrepreneur John Florey was looking for his next big thing. Florey reasoned that Russia was known for its vodka, the way France was known for wine, the Caribbean for rum, and Scotland for scotch whiskey. Russia was also known for producing the AK, and the Kalashnikov had already achieved global cult status. For Florey, the mix of Russia’s favorite spirit and favorite celebrity seemed the perfect concoction. Over dinner one evening, the idea of Kalashnikov’s AK and vodka seemed like a sure shot.

Florey had been a representative for chess champ Gary Kasparov and understood how to promote Russian culture. He had also helped to establish the Moscow Business School, so he was introduced to Kalashnikov in 2001 through the school.

Kalashnikov was interested albeit wary of the idea. He had been burned several times before. The failure of Kalashnikov’s first excursion into the world of vodka branding was not lost on Florey, who approached this project with a showman’s vision for big, bold promotions but without leaning too heavily on the gun angle. He believed that the previous vodka deal did not “extend” the Kalashnikov brand. He also brought a solid business plan. Kalashnikov was named honorary chairman of the “Kalashnikov Joint Stock Vodka Company (1947) plc.” and was to receive a small equity stake and 2.5 percent of net profits for using his name and likeness on the bottle. A 1947 picture of a young and vibrant Kalashnikov was etched into the bottles, and non-rolling shot glasses, invented by Kalashnikov himself for the Russian navy, were slated for use at bar promotions.

Florey assembled an all-star cast including David Bromige, the creator of Polstar Vodka, an Icelandic spirit that played on the motto “Strength Through Purity” along with a polar bear logo. Bromige also was a director of Reformed Spirits Company, owners of Martin Miller’s Gin, a product that had received a lot of attention for its citrus, pear, and clove flavors in Icelandic glacial water, all contained in a hip, angular bottle that bartenders liked to handle as they imitated Tom Cruise’s dexterous motions in the movie

Cocktail

. Although the brand had come into existence only in 1999, it boasted using “England’s oldest copper still.” With the opening of the former Soviet Union, vodka was growing more popular in Europe and North America as venerable vodka makers like Stolichnaya, Absolut, and Finlandia (the last two were not from Russia) were wooing younger drinkers with offbeat flavors, edgy bottles, even edgier advertisements, and higher prices that pushed prestige appeal. Florey hoped to catch the wave.

Cocktail

. Although the brand had come into existence only in 1999, it boasted using “England’s oldest copper still.” With the opening of the former Soviet Union, vodka was growing more popular in Europe and North America as venerable vodka makers like Stolichnaya, Absolut, and Finlandia (the last two were not from Russia) were wooing younger drinkers with offbeat flavors, edgy bottles, even edgier advertisements, and higher prices that pushed prestige appeal. Florey hoped to catch the wave.

The Kalashnikov 41-proof vodka was going to be produced by a distillery in St. Petersburg, with bottling done in England. Florey had to position the product just right for it all to work. Too much on the military angle would turn off drinkers. Too little and it was just another vodka. Florey pushed a well-honed message: “Kalashnikov stands for Russian design, integrity in so far as the product is true to itself, comradeship and strength of character, which epitomizes the General’s life and the role he has played in Russian culture.”

The company’s public offering went well with investors—it was oversubscribed—and listed on the United Kingdom’s JPJL market, a junior market to the OFEX, the country’s independent market focused on small and medium firms.

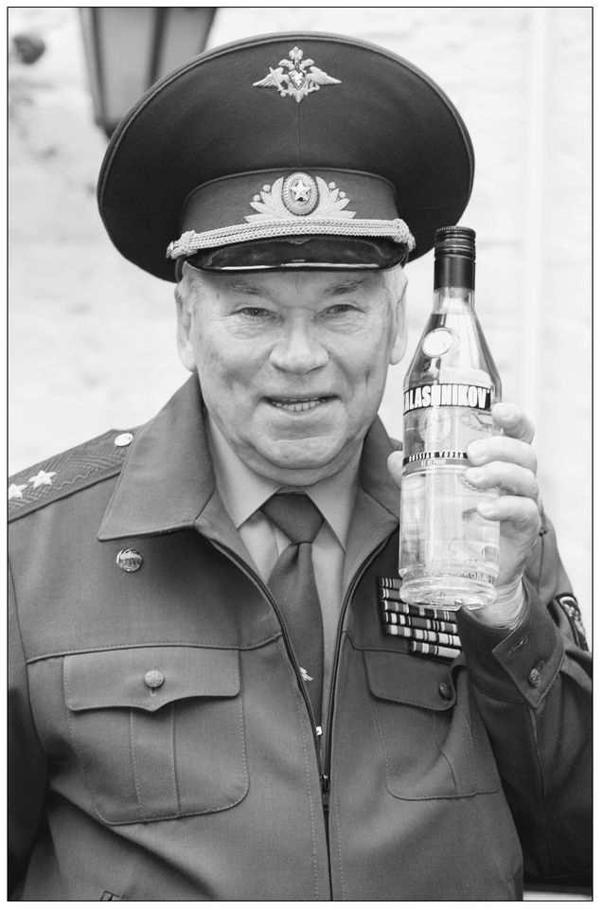

Florey’s approach was spot-on. Having Kalashnikov as your pitchman guaranteed that the story would be picked up by the world’s major media. By the summer of 2004, Kalashnikov, clad in his honorary general’s uniform complete with colorful ribbons, graced the pages of magazines and newspapers worldwide. Instead of holding an AK across his chest with his traditional two-handed grip, Kalashnikov delicately raised a martini glass up to the camera in a mock toast. This was a brilliant promotional trick; even though vodka was usually served in regular glasses, the martini glass’s unique triangular shape was instantly recognizable as a cocktail drink, whereas a normal cylindrical glass could have contained any ordinary liquid. There was no doubt that the AK-47’s inventor was enjoying a shot of liquor.

At the official launch at London’s Century Club, Kalashnikov stayed on message, too. In Russian, he said to the crowd, “I would like the product we are about to launch to be as reliable and easy to use as my gun.” It would be a message that he would repeat on many other occasions.

The reception included samples served to the crowd by Natasha, Anoushka, and Ivana, models clad in white, military-type uniforms and short skirts and known as the “Nikita Girls.” Their role was to visit bars during promotional efforts to push the Kalashnikov brand.

In an effort to cash in on his weapon’s newly established status as a cultural icon, Kalashnikov lent his name to a branded vodka. “I’m not interested in war anymore—only my military-strength vodka,” he said.

The Kalashnikov Joint Stock Vodka Co. (1947) plc.

The Kalashnikov Joint Stock Vodka Co. (1947) plc.

In interviews after the reception, Kalashnikov said, “I am to blame only for having designed a reliable weapon. . . . I am very sad when I see my weapon being used when they shouldn’t be used, but the designer is not to blame. It’s the politicians who are to blame.” Like a good soldier, he also stuck with his commercial message during public appearances touting the new brew. “I’ve always wanted to improve and expand on the good name of my weapon by doing good things,” he said. “So we decided to create a vodka under my name, and we wanted that vodka to be better than anything made up until now in both Russia and England.”

In less public moments, however, he expressed his resigned reluctance at becoming a shill, saying, “What can you do? These are our times now.” As he had been for most of his later life, Kalashnikov found himself torn between the capitalist reality of making money in the New Russia and holding firm to his lifelong Communist belief that what matters is doing your duty for the motherland without any thought of financial compensation.

Propelled by Florey’s skill and Kalashnikov’s notoriety, the vodka juggernaut was on a tear. Hip magazines like

FHM

placed it among the top ten best vodkas in their staff taste tests. Talk Loud PR, a public relations firm that had worked on the Polstar Vodka account, convinced bartenders to create trendy drinks using the vodka and submitted them to magazines. The London

Sunday Times Style

magazine displayed a picture of actress Julia Roberts with the caption reporting her interest in a drink called a Scorpino that contained Kalashnikov Vodka. The soft-porn men’s magazine

ICE

featured an irreverent Q&A with Kalashnikov along with a pictorial titled “Raise Your Glass the Ruskie Way,” on how to drink vodka in the traditional Russian style.

FHM

placed it among the top ten best vodkas in their staff taste tests. Talk Loud PR, a public relations firm that had worked on the Polstar Vodka account, convinced bartenders to create trendy drinks using the vodka and submitted them to magazines. The London

Sunday Times Style

magazine displayed a picture of actress Julia Roberts with the caption reporting her interest in a drink called a Scorpino that contained Kalashnikov Vodka. The soft-porn men’s magazine

ICE

featured an irreverent Q&A with Kalashnikov along with a pictorial titled “Raise Your Glass the Ruskie Way,” on how to drink vodka in the traditional Russian style.

The initial $90,000 public relations blitz was paying off. The company was on the way to its goal of selling forty-four thousand cases by 2006 to bars and restaurants before targeting the retail trade. Florey even hoped to place a new phrase into the English drinking lexicon: “I went out last night and got Kalashed.”

Then a problem arose.

Alcohol Focus Scotland, a group dedicated to “changing Scotland’s drinking culture,” complained to the Portman Group, a regulatory body funded by the drinks industry. It claimed that Kalashnikov Vodka “suggested an association with bravado, or with violent, aggressive, dangerous or anti-social behavior,” and therefore violated the group’s code of practice.

Complaints of this nature were fairly common as drink makers pushed the envelope as far as they could to create interest in their products, especially among younger consumers. For instance, during the time that the Portman Group was deliberating possible action against Kalashnikov Vodka, it was considering other breaches including whether a line of “tube drinks” named Blow Job, Orgasm, Foreplay, and Bit on the Side violated regulations because they implied a connection between alcohol use and sexual behavior, a group no-no. Another complaint at the time was that a pair of vodka drinks named Rocket Fuel Vodka and Rocket Fuel Ice, in concert with their prominent positioning of their very high alcohol content, 42.85 percent, were clearly using the intoxicating effect to sell themselves, another breach of the code. Both were found to be violations.

Other books

Breathing Underwater by Alex Flinn

The Indestructibles by Phillion, Matthew

La velocidad de la oscuridad by Elizabeth Moon

Trail of Blood by Lisa Black

Storms Over Africa by Beverley Harper

Smolder: Trojans MC by Kara Parker

Breath of Life (The Gaian Consortium Series) by Pope, Christine

Arizona Renegades by Jon Sharpe

Old Songs in a New Cafe by Robert James Waller