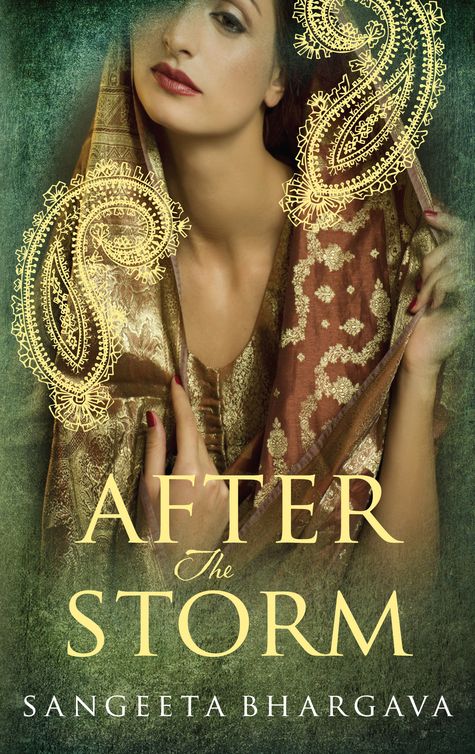

After the Storm

Authors: Sangeeta Bhargava

SANGEETA BHARGAVA

To Chotu

Title Page

Dedication

Chapter One

Chapter Two

Chapter Three

Chapter Four

Chapter Five

Chapter Six

Chapter Seven

Chapter Eight

Chapter Nine

Chapter Ten

Chapter Eleven

Chapter Twelve

Chapter Thirteen

Chapter Fourteen

Chapter Fifteen

Chapter Sixteen

Chapter Seventeen

Chapter Eighteen

Chapter Nineteen

Chapter Twenty

Chapter Twenty-One

Chapter Twenty-Two

Chapter Twenty-Three

Chapter Twenty-Four

Chapter Twenty-Five

Author’s Note

Glossary

Acknowledgements

About the Author

By Sangeeta Bhargava

Copyright

March. 1947. The year that would go down in history as the year India won its independence from colonial rule. But the speech Mili had just delivered had nothing to do with India’s freedom or the British.

Mili joined her hands and said, ‘Namaste,’ as the hall burst into applause. She stepped off the podium and went outside. Taking a deep breath of the pine-scented air, she tightened her shawl about her. She had forgotten how crisp and cool Kishangarh was at this time of the year. She looked at the greenery and the unspoilt beauty all around, from her vantage point at the top of the hill. The pine, deodar and chinar trees, the still waters of the lake below, the Himalayas in the distance. She watched half a dozen mountain goats bleating their way down the hill, led by a couple of Kumaoni girls with peachy skin and cheeks as red as strawberries.

A young Bhutia lad was trudging up the hill. He was

bent double under the weight of the three pitaras he was carrying on his back. He reminded Mili of Badshah Dilawar Ali Khan Bahadur. She smiled. It had been a similar day in March, in the same town, when she first met him, oh so long ago. How long ago was it? Six years? Just six? It seemed more like twenty.

Mili stared at the chain of snow-covered mountains, the mighty Himalayas. They always reminded her of Ma’s string of Hyderabadi pearls – sparkling, clear and smooth. If only life was like that.

She stood upright. Who was that talking to the gatekeeper? Raven? She shielded her eyes from the glare of the sun with her hand and looked more intently. Yes, it was him. A faint smile flickered across her face. Was that a hint of a pot belly, she wondered, her smile broadening into a grin. He had put up the lapels of his jacket to keep out the cold. It added to his charm – making him look casual and yet smart.

She started running down the gravel path. But by the time she reached the gate, he was gone. She looked down the hill in dismay, then turned to the gatekeeper. ‘The English gentleman you were speaking to a moment ago?’

‘Nothing important, memsahib. He only telling me give this note to Malvika Singh …’

Mili snatched the piece of paper from him. ‘That’s me. The note’s for me.’ Clutching it in her hand, she walked over to a deodar tree near the gate. Leaning against the tree, she began to read it. It didn’t say much. Just that he was surprised to see her after all these years and would she care to join him for tea at his house that evening.

She stared at the note. A chiselled, lean face with hazel eyes stared back at her. Raven. He was laughing at her … now he was scolding her and Vicky … and now that his back was turned, Vicky was sticking out her tongue at him …

1941. Mohanagar. A lazy February afternoon. The palace slumbered while a wintry sun kept its vigil. Mili, however, was wide awake and stood looking out of her window. She watched with an amused smile as Vicky pulled herself up the low wall that surrounded the inner courtyard of the palace. Jumping to the ground with a thud, Vicky dusted her palms on her frock. Mili stood still. The sound had woken up one of the doorkeepers. She shook her head as he mumbled, ‘Oh, Vicky baba,’ and went back to sleep. Nice cushy job he had. All he had to do to earn his salary was to sleep at his post.

She turned her attention back to Vicky. She was looking around carefully. Then she scampered onto the veranda and threw a tiny pebble at Mili’s window. Mili hid behind the golden drapes and urgently held her finger to her lip as Bhoomi began to giggle. As soon as Vicky leant against the windowpane and peered in, Mili swung it open.

‘What th—’ Vicky cried as she fell into the room. Mili burst out laughing. Bhoomi stood in a corner with the edge of her sari over her mouth to suppress her giggle.

‘What the devil …’ Vicky mumbled as she came towards Mili, hands on her hips. Mili tried to back off but Vicky had grabbed her shoulders. ‘Mili,’ she shouted as she shook her.

‘Y-yes?’ replied Mili, pretending to be frightened, a frown creasing her forehead.

‘I’ve got admission in STH.’

‘I know,’ replied Mili, as Vicky loosened her grip.

‘How’d you know?’

‘Because …’ Mili’s bright eyes twinkled as she waved an envelope at her, ‘I just got my admission letter as well.’

The two friends hugged each other excitedly, like fledglings that had just discovered they could fly.

‘Such fun,’ squealed Vicky, as she pushed back her thick-rimmed glasses from the tip of her nose. ‘No more of this boring city. Where nothing ever happens …’

‘And just think,’ added Mili, fiddling with her hair that Bhoomi had plaited and tied neatly into rolls with blue ribbons, ‘no more having to take Ma’s permission for every little thing or Bauji’s ifs and buts. Oh Vicky, I’m so thrilled.’

Vicky lifted her chin and looked down her nose at Mili. ‘Princess Malvika Singh. Say thank you to Miss Victoria Nunes. If it wasn’t for my illness, you—’ She stopped speaking and gestured to Mili to look behind her. Mili turned around with a start and almost bumped into Ma.

Ma did not speak, merely nodded her head as Vicky and Bhoomi joined their hands and bowed. Mili shifted uncomfortably and began chewing her thumbnail as Ma turned to look at her. Nobody spoke. The only sound that could be heard was that of the tennis racquet hitting the ball, from the court adjoining the veranda. Must be Uday playing with that new friend of his.

‘Is it true you’ve got admission to that school in Kishangarh?’ Ma finally asked.

‘Yes, Ma,’ Mili replied, looking down.

‘I’d better go,’ muttered Vicky and started to climb out of the window.

‘We do have doors, you know,’ Ma said, a bemused look on her face. She had never been able to fathom Vicky’s ways.

Vicky scratched her head and grinned foolishly before replying, ‘Yes, of course. I forgot.’

Ma raised her hand. ‘Stay and hear us out,’ she said. She cleared her throat. ‘Mili, we know we let you apply for admission to that school on Mrs Nunes’ insistence and you have our permission to go. But your Bauji will need some convincing.’

‘Please talk to him, Ma,’ Mili said as she clutched her hand. ‘You can do it.’

‘Yes, Your Highness. He listens to you,’ added Vicky.

‘We’ll see what we can do. But it won’t be easy,’ replied Ma, thinking hard.

‘Can Mili come? With me? To see my mother?’ Vicky asked. ‘She’ll be thrilled.’

Ma looked at Vicky and then at Mili, slightly perplexed. Mili grinned. Vicky’s mind was like a racehorse, galloping from one thought to the next.

‘Please, Ma? Can we go break the news to Mrs Nunes?’ begged Mili.

‘You know we don’t like to send you to town these days because of the freedom movement. Not to mention the war …’

Mili looked at Ma with pleading, watery eyes. Ma hesitated for a moment, then shrugged her shoulders. ‘All right, then,’ she replied and turned to Bhoomi, who

had been standing quietly near the door all this while.

‘Bhoomi, tell Tulsidas to take Princess Malvika and her friend to Mrs Nunes’ clinic and to bring her back in two hours.’

‘Yes, Your Highness,’ answered Bhoomi as she joined her hands, bowed and backed out of the room to look for the chauffeur.

Mili grinned at Vicky, then hugged Ma. She always smelt of sandalwood – so pious and righteous that Mili found herself examining her conscience whenever she was in her presence. ‘You’re the best mother in all the land,’ she whispered.

‘Save those words for your father,’ Ma replied as she left the room, her fragrance still lingering.

Mili walked over to her dressing table. She adjusted her blue silk dupatta and straightened the sapphire on her necklace, caressing its smooth surface as she did so.

‘Isn’t it tiresome? All this jewellery?’ Vicky asked.

‘Not at all,’ Mili replied. ‘I love it.’

Vicky stood behind her and grinned at their reflection in the gilt-edged mirror. ‘Mummum will be pleased.’

Mili looked at her and smiled. Vicky had a plain, flat face and her huge glasses gave her an unnaturally solemn look. But the moment she grinned, her entire face lit up, her eyes laughing with such merriment that one couldn’t help but smile back at her.

‘Let’s go. Ma will worry if we don’t get back before dark,’ said Mili, as she pulled Vicky towards the door.

Vicky looked at the clock that hung on the wall behind Mummum’s desk. It had taken them twenty minutes

to reach her clinic from the palace. She yawned as Mummum continued to talk into the telephone. She pulled a face at Mili, who sat primly and patiently beside her. How was it possible for someone to be so well behaved all the time? she wondered. She looked around at the bare walls. Why were hospitals and clinics always so boring? Wouldn’t the patients get better faster if they had something cheerful to look at?

That’s it. She couldn’t sit still a minute longer. Her chair scraped noisily against the concrete floor as she got up. She walked over to the table that stood against the wall at the right-hand corner of the room. After scrutinising the bottles for a moment, she picked up one. Unscrewing the lid, she sniffed at it, screwed up her nose at the pungent smell and hastily slammed the lid. She opened another. ‘Yuck, this smells like phenyl,’ she muttered as she picked up a third. Umm, this didn’t smell bad at all. And the syrup looked thick, like malt. She wondered if she could taste it. She looked at Mummum. She was still on the phone but was watching her from the corner of her eye and glared at her. Vicky pulled a face again, put the bottle back on the table, pushed back her glasses and went and sat down.

‘Mummum, I’ve got admission!’ Vicky had sprung to Mummum’s side even before she had replaced the receiver on its cradle.

‘Good heavens,’ exclaimed Mummum. ‘Is it true? Is it really true?’ She hugged Vicky and kissed her hard, then embraced Mili. ‘I always knew you’d be the one to do me proud. Those sisters of yours are useless.’ She paused to look at her daughter’s face and pat her hair. ‘Mrs

Gomes,’ she trumpeted to her secretary, ‘my Victoria here has secured a place at the School for Tender Hearts in Kishangarh.’

Mrs Gomes looked up from her typing and hurried over to congratulate her. She shook Mummum’s hand, then patted Vicky’s head. ‘Well done, Vicky,’ she said.

‘Victoria, Mrs Gomes, Victoria. You wouldn’t call Queen Victoria “Vicky”, now would you?’

Mrs Gomes licked her lips. Before she could reply, the other nurses and doctors had started filing into Mummum’s cabin, having heard the news.

Vicky noticed the smug look on Mummum’s plump face and smiled. Moments like this had been rare in her mother’s life. Her family had severed all ties with her when she married Papa, as he was an Englishman. Relatives are cruel. They even regarded Papa’s untimely death as divine justice and refused to accept her back into the fold. But Mummum was a proud woman. She faced life head-on. She worked hard to reach where she was now and Vicky was proud of her.

‘Thank you, thank you,’ Mummum’s loud voice boomed for everyone to hear. ‘And did you know STH Kishangarh is amongst the most acclaimed schools in this country? Until recently, ninety-five per cent of the students there were English.’

Vicky grinned as everyone exclaimed and congratulated her once again.

‘Madam, this calls for a celebration, a par—’ said Pankaj.

‘Yes, why not?’ Mummum cut in. ‘And Pankaj, don’t forget to invite Mr Chaddha. Let’s see if I can persuade

him to change the second clause of the contract during the party.’

‘Yes, ma’am.’ With those words the staff dispersed and Mummum turned her attention to Mili. Taking her in her arms she exclaimed, ‘I’m so happy, my child, that you’re going to be there with my Victoria.’

Just then Tulsidas came into the room. He joined his hands and said, ‘Beg pardon, ma’am, but I fear there be rumours of trouble brewing in town. Because of the arrest of them revolutionaries.’

‘Good heavens, in that case … come on, girls,’ Mummum said impatiently, shoving the two girls towards the door. ‘You had better hurry. Oh, dear Lord, don’t let my girls come to any harm.’

Vicky walked towards the car with Mili, then went back to give Mummum another hug. She grinned as Mummum frowned at her with feigned anger, lightly smacked her on the head and said, ‘Off with you now.’

Vicky and Mili got into the Rolls-Royce. What trouble was that Tulsidas talking about? As far as Vicky could see, there was nothing unusual. It was evening. The bazaar through which they were now passing was as busy as it normally was at this time of the day. He had got Mummum all worked up for nothing.

Vicky looked out of the window. The sweet smell of jalebis wafted into the car and made her realise it was nearly time for supper. She looked longingly at the orange, syrupy sweets. The roadside vendor had piled the intricately curled jalebis one on top of the other to make a mini mountain. They beckoned to Vicky and she

was tempted to ask Tulsidas to stop the car. But no, Mili was not allowed to eat anything off the streets.

‘Do you think we’ll get jalebis? In Kishangarh?’ she asked Mili, imagining herself biting into one and the orange syrup spilling over her tongue and gushing down her throat.

‘You know, I was looking at some pictures of Kishangarh. And the winding road that ran down the mountain to the valley below looked just like a jalebi.’

Vicky rolled her eyes. Mili grinned and stuck out her tongue at her.

‘Are you taking Bhoomi along? To Kishangarh?’ Vicky asked, pushing back her glasses.

‘Heavens, no. That would defeat the very purpose of my going there, wouldn’t it? I want to stay there, with you, in the boarding school. See what life is like outside the palace.’

‘But what if—’ Vicky stopped abruptly as she realised the car had slowed down considerably, owing to a large crowd that had emerged out of nowhere. There were hordes of men clad in khadi kurtas, white pyjamas and white caps. Some of them were carrying banners and shouting slogans. Others waved the Congress tricoloured flag. Every so often they would raise their hands in the air and shout, ‘Bharat Mata ki Jai. Down with imperialism. Release our comrades from prison. They’re innocent.’ There were even some women in the mob, dressed in starched cotton saris and shouting alongside the men.