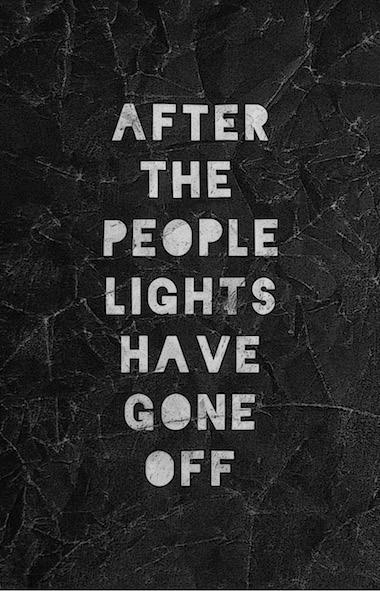

After the People Lights Have Gone Off (23 page)

Read After the People Lights Have Gone Off Online

Authors: Stephen Graham Jones

Tags: #Fiction, #Ghost, #Short Stories (Single Author), #Horror

•

That afternoon, Maddy used the ten-inch forceps to help a butterfly unfold from its cocoon.

The light in the terrarium was meant to simulate sunlight, and, while it cycled at the proper times—not an off-switch, but gradually fading, then slowly warming again hours later—Maddy was increasingly certain there was some vital element not reproducible with light bulbs. Thus the forceps, the help.

“There you go, there you go,” she cooed to the butterfly.

The butterfly was twenty-eighth generation.

Sixteen generations ago—twelve generations in, so Maddy could record what was baseline, chart what was to be expected—Drs. Romin and Chang next door in Commercial had introduced an amino acid to the brood of caterpillars.

Maddy’s task now was what it had been for the past year and a half: monitor, record, and report at prescribed intervals, so Romin and Chang could write their reports for Commercial’s director to approve, forward on to the make-up company.

While some of the science that went on in this wing was maverick and revolutionary and potentially paradigm-toppling, a bigger portion was corporate lipstick jobs—a term in play well before Maddy had hired on.

Zenomarque Laboratories had been contracted to push the caterpillars through forty generations, for what the eventual packaging would probably call “quality control.”

The amino acid now cycling through this cultivated variant of

Hemiargus isola

was nothing new, either; she was pretty sure it already had cousins on the shelf in cosmetics. But butterflies of course don’t stop by the beauty counter. They don’t need anti-aging creams.

However, to keep her vision properly tunneled—let others interpret, hypothesize—she didn’t research or otherwise prejudice herself. Otherwise the results would always be suspect, at least to her.

In the artificial sunlight, now, specimen G44H3a was drying its wing luxuriantly.

Maddy stepped over to check the patterning on the wings, see if it was still symmetrical, and gasped a bit.

Eyes.

And then she laughed at herself.

Eyes like a peacock’s tail feathers, eyes like some moths’ wings, eyes like the

Mycalesis patnia

were faithfully expressing in the other terrarium generation after generation,

“eyes”

like the

Bicyclus anynana

Maddy had read about: mimicry-as-survival strategy. All this

Hemiargus

wanted to do was fend off its eventual predators. It was designing itself well.

Except—these

“eyes”

were distinctly hazel, and seemed to be striated concentrically, even.

An almost familiar pattern. One only a mother would know.

Maddy slapped herself on the wrist, shook her head no.

She

had

had long enough to grieve, she told the Dr. Corinth in her head.

She had.

Still, it was her assignment to record every last minutiae, so she did, even lightly sketching in the suggestion of pupils, and noting how they seemed to track the viewer.

You never know what’s going to matter.

•

Sixteen days later, at what should have been the end of G44H3a’s life—the lab had ordered this particular strain for its advertised brevity, allowing them to reach forty generations quicker—instead of fluttering around with senility, its stimulus-response little brain winking out cell by cell as nature intended, a grand torpor settling in across its light frame, G443H3a instead began to form a cocoon.

Maddy tapped her pencil against her lower teeth and puzzled over this.

This

is why she’d gotten into science, she finally told herself, allowing herself a grin.

To artificially extend a butterfly’s life, discover that the world had never known the butterfly at all. At least not in its true form. Either it was programmed to cocoon at regular intervals, some undiscovered alarm clock in its metabolism telling it

now

,

now

, never knowing that this cocoon was to be a mausoleum, or else it was escaping death by transforming again and again—into

what?

Meaning all along it had had multiple instars coded into its DNA, just waiting for this particular combination of amino acid and artificial light to express them.

But to what end, finally?

Maddy started a new log, a private log, and, though it was policy to leave the terrarium key on the hook by the specimen drawer, that night she left them in the back of the file cabinet. As if she’d forgetten them there while looking for some paperwork.

Completely understandable.

•

Eight painful days later, G443Ha’s cocoon trembled with life.

Maddy helped with her probe and forceps as much as she could. The videocamera hummed on the counter beside the terrarium, recording these momentous events.

What the camera caught on its grainy screen was—it was a

lizard

. Of sorts.

Before Maddy could catch it, it scampered into the foliage.

Maddy blinked, swallowed, tried to breathe.

Had it gotten into the terrarium on its own, burrowed into the cocoon and slurped up the newborn?

Maddy hoped not.

•

The next morning was carnage. Maddy walked into the lab to find Drs. Romin and Chang at her desk, flipping through the log.

Her heart spiked, but then it was just the public log, not the diary she’d been keeping.

“Doctors?” she said, her hand still to the doorknob.

Dr. Corinth stood from the other side of the terrarium.

“Looks like you’ve had a fox in the henhouse,” he said, and directed Maddy over.

The rubber seal in the rear corner of the terrarium had been leaking—the misters ran at regular intervals—was cracked now, very finely.

“Here’s where it got in,” Dr. Corinth said.

“Twenty-eight generations,” Romin said, pooling his fingers out to show where those twenty-eight generations had gone.

“Not her fault,” Chang said.

He had been at the memorial, Maddy was pretty sure. Not because he knew her—he didn’t—but way in the back, as if fulfilling a personal debt. As if keeping a secret promise.

“Faulty equipment,” Dr. Corinth finally agreed, though something about his tone suggested that this conclusion was a one-time compromise.

“You can manage the maintenance form?” Romin asked.

Maddy nodded, dazed.

“And order more of the . . . the—”

“

Hemiargus isola

,” Maddy filled in, her face flushing.

“I am sorry,” Chang said, squeezing her upper arm on his way past, for the door.

“We all are,” Romin added, and then they were gone.

On the gravel bed of the terrarium were the savaged remains of the whole twenty-eighth generation.

Maddy closed her eyes.

When she opened them, the lizard was looking back at her through the glass.

Its eyes were hazel, the irises striated, the pupils a deep well.

•

Protocol was to sterilize the terrarium in preparation for the next brood. To gas the lizard out. To defoliate, to run the gravel through the scrubber. To dip the glass walls, completely remove the contaminant.

The new order of

Hemiargus isola

was still six weeks out, though.

Maddy opted to monitor the lizard, the one with the heart of a butterfly.

It was the twenty-

ninth

generation.

•

The next day, its belly full, the lizard burrowed into the decay, pulled the covers around itself again and again, tighter and tighter.

It trusted Maddy.

She casually locked the door, threaded the private log from the file cabinet. Cued up the videocassette she’d since replaced.

The artificial sun went down, came up, and went down again.

Four days later, a mouse pup nosed through the soil.

Maddy cried.

In the private log she wagered that every planet produces one animal that contains every form of life. A genetic chimera. For purposes of repopulation following some global calamity.

This had probably happened before.

Just, never in a lab.

And, though Maddy knew what the calamity in this case had been—Chang could have guessed as well, she would wager—she didn’t write her son’s name in the log even once.

•

Three accelerated generations later—they ate the cocoon now, and whatever else she could smuggle into the lab—Maddy recorded the birth of what she strongly suspected would grow into a star-nosed mole, if given the chance. Something burrowing, anyway. Something born pregnant. With itself.

Maddy’d taken to sleeping less, in order to document. And Dr. Corinth didn’t bother her about grieving anymore. She was the busiest body in the lab, helping out in each experiment, always checking the day’s mail for her shipment of

Hemiargus isola

.

Soon enough, after gnawing down a pigeon Maddy had trapped under a cardboard box on the balcony of her apartment, the mole developed enough to gecko up the glass wall of the terrarium, spit a cocoon around itself in the high rear corner.

Maddy camoflouged it as well as she could, all the while recording temperature and sound, and humming to it in case it needed to know her voice. Even on the bus, she noted, she was humming.

It wasn’t a bad thing.

Two mornings later, she found Dr. Corinth probing the flaky shell of the cocoon with a probe.

Maddy’s coffee dropped, and she didn’t even register the splash on her shins.

“Dr. Greenwald?” Dr. Corinth said to her, his pants legs spattered as well.

“It’s, it’s—” Maddy said.

“Amazing,” Dr. Corinth said.

Drs. Romin and Chang agreed.

Thermal readings were taken, and taken again. Evidently the reason the cocoon was flaky was due to the exothermic process happening within, that Maddy’s delicate thermometer hadn’t pushed deep enough to feel.

The flakes from the cocoon were preserved, frozen, wondered at.

Other lab personnel toured through. The way they held their eyes was the way photographers hold their cameras at important but fleeting social events. Because they knew this area was soon to be cordoned off, Maddy knew, and didn’t want to know.

In an effort for her access not to be revoked, she produced the private log, the secret videorecordings.

“I call him Gabe,” she said.

Chang’s eyes flashed up to her about this, but he didn’t say anything.

Nobody was thinking about the lipstick job anymore. Instead they were all composing their speeches, for the awards that had to be coming.

Drs. Corinth and Romin and Chang and the other lab-coated rubberneckers retired to the break room at mid-afternoon. The big television was there. They wired Maddy’s camera to it, watched birth after birth, freezing the frame to argue. Each instar confirmed a suspicion. Each new life was the first of its kind, a new entry into the fossil record.

The tree of life was branching into finer and finer filaments.

For them, anyway.

Maddy stood alone in what had been her lab.

Meaning she was the only one there when the cocoon trembled again.

Calmly, watching her hand more than controlling it, she disconnected the leads that would have drawn everyone in from the breakroom.

The cocoon shuddered, cracked, and dripped, finally exhaled a moist breath of steam.

Maddy helped it down to the floor of the terrarium.

The cocoon weighed 1905.1 grams. Dr. Corinth had written it down already.

X-rays were scheduled for this evening.

Now they wouldn’t be necessary.

Maddy dialed the light down, used forceps and a probe to separate the fibrous tissue.

Two eyes looked through to her from another world.

Two eyes with dark pupils swimming in hazel, striated irises.

Then a hand pushed through, reaching for her.

Maddy touched her own throat with her fingertips, realized she’d been humming again.

Five fingers, she noted.

Human.

Maddy shook her head no, no, and parted the cocoon more, more, enough to see that this wasn’t Gabe at all, like she’d been insisting.

This was Taylor.

Again.

Each letter of his name had cost seventy-five dollars, in granite.

It was a price she hadn’t anticipated.

Gabe was better, more economical.

Or, no: Ty. Ty would be perfect.

Maddy nodded to herself, her eyes crinkling in amusement at her folly, and then, just like last time—in science, you learn about repetition, about achieving the same results—she held her hand over Taylor’s small wet mouth, and counted him back to sleep.