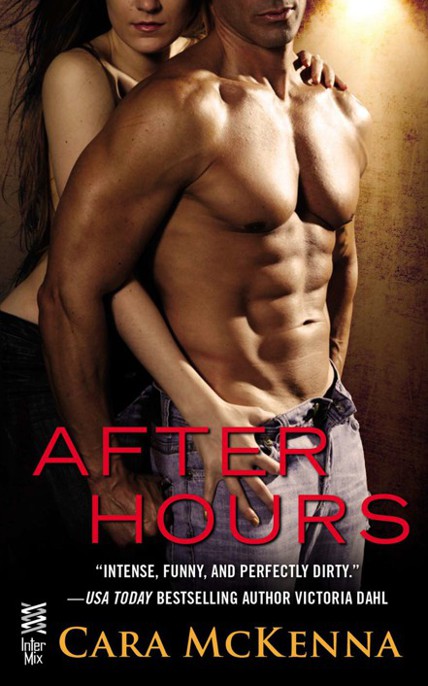

After Hours

INTERMIX BOOKS

Published by the Penguin Group

Penguin Group (USA) Inc.

375 Hudson Street, New York, New York 10014, USA

USA | Canada | UK | Ireland | Australia | New Zealand | India | South Africa | China

Penguin Books Ltd., Registered Offices: 80 Strand, London WC2R 0RL, England

For more information about the Penguin Group visit penguin.com

This is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places, and incidents either are the

product of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously, and any resemblance

to actual persons, living or dead, business establishments, events, or locales is

entirely coincidental. The publisher does not have control over and does not have

any responsibility for author or third-party websites or their content.

AFTER HOURS

An InterMix Book / published by arrangement with the author

PUBLISHING HISTORY

InterMix eBook edition / April 2013

Copyright © 2013 by Cara McKenna.

Excerpt from

Unbound

copyright © 2013 by Cara McKenna.

All rights reserved.

No part of this book may be reproduced, scanned, or distributed in any printed or

electronic form without permission. Please do not participate in or encourage piracy

of copyrighted materials in violation of the author’s rights. Purchase only authorized

editions.

For information, address: The Berkley Publishing Group,

a division of Penguin Group (USA) Inc.,

375 Hudson Street, New York, New York 10014.

ISBN: 978-1-101-62198-1

INTERMIX

InterMix Books are published by The Berkley Publishing Group

and New American Library, divisions of Penguin Group (USA) Inc.,

375 Hudson Street, New York, New York 10014.

INTERMIX and the “IM” design are trademarks of Penguin Group (USA) Inc.

Chapter One

I heard the sign before I saw it, bent metal rattling in the breeze as my car rounded

a curve.

DO NOT PICK UP HITCHHIKERS!

The directive was bisected by a ribbon of red rust, as though the sign were bleeding

out from its bolt.

Duh-duh-dunnn . . .

Cue the requisite horror-movie music.

But ominous sign notwithstanding, the road was quiet and pretty. Elms and oaks and

firs rose up on either side, watery dawn sunshine winking between green leaves to

the east. There were no pop bottles or old fast-food bags littering the roadside,

those scraps of urban apathy I’d grown so used to, living in southeast Michigan my

entire life.

Too quiet and pretty,

my paranoid inner narrator whispered.

My eyes narrowed at an elderly man shuffling along the shoulder with a walking stick.

Though he looked harmless, I knew better than to trust such a thought. But he didn’t

acknowledge my approach let alone try to thumb a lift, so I decided he probably

was

just an old man, out for an early stroll on a June morning.

Then again, I was heading in the wrong direction. If he’d just escaped from a mental

institution, hitching a ride from me would land him right back where he’d come from.

My heart slowed when a bend in the road took him out of my rearview.

I spotted the gate first—a tall, stately gate, its wrought iron glossy with a fresh

coat of black paint, and the name

Larkhaven

glowering from fifteen feet up, flanked by security cameras. I could feel them blinking

at me, curious as crows. I edged my cranky sedan forward to a brick pedestal, and

leaned out to press a button below a panel labeled

Intercom

. A vision of a hand grasping my wrist flashed across my brain and I yanked my arm

back inside, bonking my elbow.

“Mother—”

A speaker crackled, followed by a bored female voice.

“Good morning. What brings you to Larkhaven today?” This was the guest entrance, I

knew, and employees, deliveries, drop-offs, and pick-ups usually came the back way.

But I didn’t have security clearance yet.

“I’m Erin Coffey,” I told the panel, rubbing my elbow. “I’m starting today, with Dennis

Frank?” Was I? It came out as a question, like I didn’t really believe it myself.

“Hang on.” Silence, then another crackle. “Okay, come on in. Employee lot is all the

way around to the left. Follow the signs to the Starling building and the staff entrance,

and hit zero on the intercom.”

The gates glided in, divorcing the

Lark

and

haven

. I cranked up my window on the sweet spring air and punched down the door lock.

I drove slowly, taking in the grounds as I passed a stand of pines. If it weren’t

for the imposing black fence, it would’ve passed for a small private college—five

or six three-story yellow brick buildings connected by paved walking paths, green

lawns dotted with benches. Nicely maintained, if a bit worn around the edges. A bit

eerie as well, with no one to be seen save for a tall woman in blue scrubs, speed-walking

across the grass.

The main hospital that governed Larkhaven was a quarter mile away, this campus dedicated

to outpatient programs serving those with developmental issues, mental illness, substance

abuse problems and the like, along with several short-term residences, plus an eldercare

facility with a focus on Alzheimer’s and dementia.

Skylark,

one building’s prominent placard proclaimed.

Warbler

,

said another, and

Waxwing.

The employee lot was just behind the building labeled

Starling

,

Limited Access

. My building. Made sense, that the locked ward would be closest to the drop-off zone.

I eyed the windows as I pulled into a free space, searching for signs of violence

and chaos, confirmation that I’d made a Big Mistake, but I saw only slim metal bars.

They were a grim comfort, at least while I was outside. They kept the scary people

in. But once I was inside, I might not find them so reassuring.

And I didn’t mean it, about them being scary people. The mentally ill had enough stigmas

to bear without a psych professional casting aspersions.

But I

was

scared. It felt like someone had drawn my ribs together with corset laces, tugging

them tight, tight, tight until I couldn’t get a deep breath, lungs and heart bound.

I’d been immersed in my slow-motion nursing education for four years, now certified

as an LPN, and had spent six years as my grandmother’s live-in caregiver. She’d passed

in the winter, peacefully. A mercy, by the end. But she’d been the center of my life,

and losing her had left me adrift. My certification felt like the only anchor I had,

the only arrow pointing me toward anything.

My grandma’s dementia may have disturbed its fair share of people, but she’d been

a gentle soul, generally. She’d only ever shouted out of fear and confusion, never

anger, whereas this was a high-security ward designed specifically for men who suffered

from persistent, disruptive psychotic episodes. A dozen unpredictable, occasionally

violent men. And little old me, the LPN who’d had exactly one real patient in her

entire so-called nursing career.

And I

was

little. An inch or two shorter than average, plus after a few years on what I called

the Social Security Diet—a lot of beans and toast and soup to stretch the pathetic

amount of money the government deemed adequate to keep me and my grandma warm and

fed and clothed—I didn’t cut a very authoritative figure. I had a baby face and round

blue eyes to match, too-soft light brown hair that defied all promises made by thickening

shampoos. Once on the ward, the most intimidating thing about me would surely be the

syringe in my hand.

All my worries gathered in a scrum and elbowed for attention.

You’ll get stabbed with a plastic fork. You’ll fuck up some poor man’s medication

and give him a seizure. Your coworkers will treat the patients cruelly and you’ll

be too chickenshit to report them. Amber’s stupid redneck boyfriend will pick today

to show up and cause drama, and you won’t be there to rescue her.

Fucking Amber. My fucking sister whom I fucking loved.

I’d loved her from the moment I first held her as a baby, when I was five, but I wouldn’t

be here—taking a job that frightened me in this nowhere corner of the state—if it

weren’t for her. Her and my nephew Jack in that grubby little house on that grubby

little block, thirty minutes’ drive from Larkhaven. If I wasn’t around to check in

on them, nobody else would be doing the job. Nobody except Amber’s awful boyfriend

or ex-boyfriend or ex-fiancé or whatever she was calling him this week. Jack’s father,

she was seventy percent sure. When she was mad at him it dropped to ten percent, soared

to ninety-nine whenever they reconciled. She’d turned into our mom. Same temper, same

lousy taste in men; a too-young mother prone to impulsive, dramatic mistakes. Our

mom had worked two jobs and treated dating like the night shift. Treated dating like

playing the lottery, always imagining,

This guy will be the one to lift me out of this shithole.

She’d never been a lucky one, but you couldn’t fault her determination, putting in

the hours at the singles’ bars, upping her odds.

I’d basically raised Amber from when I was ten or so, been the one who got her up

for school, fed her, cracked the whip on homework. Not that I did such a great job,

considering she’d dropped out at sixteen. I only prayed she wouldn’t take yet another

leaf out of our mom’s book and ask me to raise her kid . . . Though mainly because

I knew, given how much I adored Jack, there was no question I’d choose to turn my

life inside out and accept.

After I shut off the engine, I held the steering wheel and counted my breaths, waiting

for my heart to slow, for those corset laces to go slack. They never did. I pocketed

my keys and stepped into the cool, damp morning air. There was birdsong all around

and the grounds smelled of spring, like the final weeks of school before the freedom

of summer. I sucked it in, knowing my first day would be busy, and that I might not

get outside again until the end of my twelve-hour shift.

My flats crunched across the gravel lot, to the door labeled

Staff Entrance

. I pushed the zero key on a bank of buttons.

“Yes?”

“This is Erin Coffey, for Dennis Frank.”

“Hang on.”

I waited in silence for a full minute or more, then the metal door swung in, and a

man was smiling at me.

“Come on in,” he said. “Welcome to Larkhaven.”

I stood aside in the little windowless foyer, and the man I assumed was Dennis let

the heavy door hiss shut before swiping another open with a keycard. He led me down

a short hall and into a cramped break room with a kitchenette, tidy but cast in a

sickly glow by the fluorescent bulbs.

Dennis looked about fifty, with gold-rimmed glasses and a professorial goatee, and

overgrown salt-and-pepper hair. He wore scrubs, pale blue, and boat shoes. He seemed

at once kind and exhausted, defeated and determined, with one of those expressive,

guileless faces that told you everything he was feeling.

“Coffey?” he asked.

“Yes,” I said. “Erin Coffey.”

“Oh, sorry, I meant, would you like some coffee?” To demonstrate, he filled a paper

cup from a carafe on the counter. When I waved it away he added a packet of sugar

and took a sip. He smiled. “Six thirty in the morning on your first day and no caffeine?

We’d been hoping to find somebody superhuman for the day shift.”

“I had a cup on the drive over.” Plus, being here had me so jittery, more coffee would

surely plunge me headlong into my own psychotic break, landing me in Larkhaven as

a patient.

“Well, Erin Coffey, I’m Dennis Frank.” We shook. He paused to check a roster of names

listed on a large whiteboard beside the door. “I’ll be showing you the ropes this

morning, before I hand you off to one of the senior nursing staff. The nurses run

this ward. You’ll see doctors around, of course, for groups and one-on-ones. But their

offices are all here on Starling One. S1. Up on the secure floors, S2 and 3, where

you’ll spend most of your time, it’s the nurses’ show.” He said it with a little air

of false haughtiness.

Dennis and I had spoken a few times already. I’d gone through the interview process

at an affiliated hospital back home, recruited via a job fair. Dennis had been present,

if only as a kind voice coming through a conference line. He was a veteran nurse himself,

turned shift manager and administrator, and he’d been working at Larkhaven for fifteen

years, most of them on the locked ward, the unit reserved for the most dangerous patients.

What shocking things had he seen in all that time? What shocks were in store for me?

My invisible corset gave a mean squeeze.

“So we’re standing in the most important room in the building,” Dennis said, swiveling,

gesturing with outstretched arms. “The coffee room. Some argue the smoking patio is

more important, but to be fair, it’s not technically a room. Do you smoke?”

I shook my head.

“Give it a week,” he teased, but the joke was playful, not cynical. “Actually where

we are now is called the sign-in room. Everyone comes in, writes their name in the

appropriate slot so we know what their duty is for the day. You’ll be signing in as

a general LPN, so easy-peasy, everyone will know to find you in the usual places throughout

your shift. But our orderlies, for example, might sign in for general duties or be

assigned for close obs on a difficult patient, so everyone will see they’re busy with

a specific resident.”

He grabbed a dry-erase marker for me, and tapped the whiteboard. I printed my first

name carefully in a free slot in the nurses’ section, and my in and out times, the

same number for both columns—seven to seven. Dennis told me to write

nurse shadow

in the duties column, so I did, picturing myself as a mysterious Batman-like figure

in a dark gray catsuit, black cape, stethoscope glinting in the moonlight.

Nurse Shadow.

A useful vision, lending me the illusion of unflagging competence until the day I’d

feel it for real.

Dennis led me next to a storage room, eyeballed me and said, “Definitely a small.”

He slid a bin from a shelf and handed me a set of butter yellow scrubs.

“The women’s lockers are through there,” he said, pointing to a door. “There’s a hamper

for the dirties, and you can grab a fresh set from in here each morning. Yellow for

the nurses and techs, green for the orderlies, blue for senior staff and managerial

scum like me. Plus the classic white coats for the doctors and therapists. The residents

in this ward wear gray. The residents in other programs are allowed to wear their

own clothes, but at Starling we keep a dress code. Some say it’s depressing, makes

it feel like a prison. But our patients do best when things are predictable—egalitarian,

if you will—and we’ve found the uniforms help.”

“Right.”

“Bring your own lock if you’ve got valuables, but don’t worry if you don’t have one

today. We’re all too tired to steal much of anything.”

I didn’t own anything of value. My cell phone was six years old, practically a brick,

and I hadn’t worn any jewelry. If anyone swiped my car keys, they’d wind up driving

off in a ’93 Ford Tempo, more orange than teal these days from the rust. The thing

had been cranky since I’d inherited it from my uncle in my junior year of high school,

and the only force holding it together now was a kind of willful, joyless, made-in-Michigan

pride. The thief was welcome to it.

I changed quickly and met Dennis back in the hall.

“Every morning at ten to seven we have a hand-off meeting in the lounge,” Dennis said

as he led me into a stairwell with another swipe of his keycard. We hiked up two flights,

then banged a left down an echoing corridor. “The overnight staff catch the day crew

up with anything that’s gone on. Ditto in the evenings. Bit old-school, but that’s

kind of the Larkhaven way, you’ll find. Usually takes five minutes or less. Then at

seven we start waking the residents.”