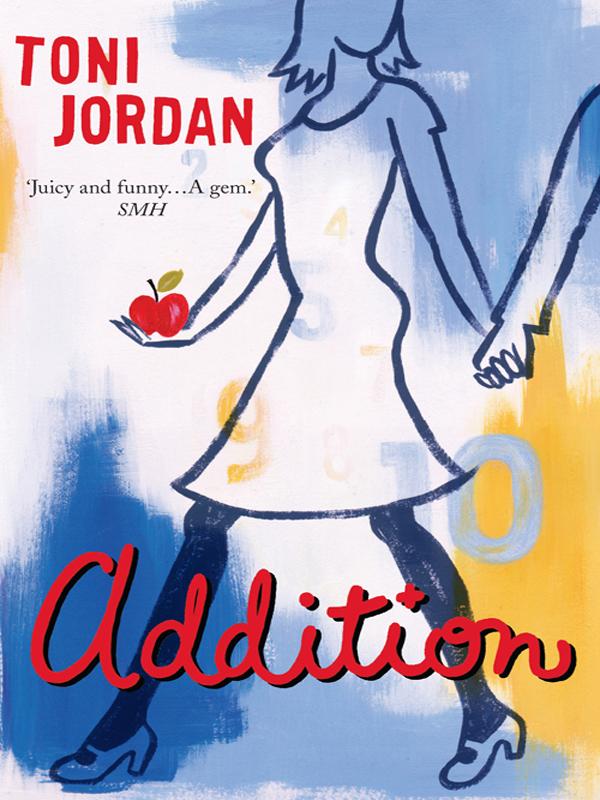

Addition

P

RAISE FOR

T

ONI

J

ORDAN AND

Addition

W

INNER,

B

EST DEBUT FICTION,

I

NDIE

A

WARD, 2008

W

INNER,

B

EST THEMED FICTION,

UK M

EDICAL

J

OURNALISTS

A

SSOCIATION 2008

S

HORTLISTED,

B

EST

G

ENERAL

F

ICTION

B

OOK OF THE

Y

EAR, 2008

A

USTRALIAN

B

OOK

I

NDUSTRY

A

WARDS

S

HORTLISTED,

N

EWCOMER OF THE

Y

EAR (DEBUT WRITER), 2008

A

USTRALIAN

B

OOK

I

NDUSTRY

A

WARDS

‘Toni Jordan has created such a real character in Grace that you are cheering her on…Jordan’s voice is distinctive, refreshing and very Australian. Her debut novel is juicy and funny, just like its protagonist…this is a gem.’

Sydney Morning Herald

‘Snappy, sassy, superior chick-lit with a twist… Jordan portrays Grace’s quirks with poignancy, pathos and, most importantly, humour.’

Canberra Times

‘Tremendously enjoyable…a romantic comedy with a light touch and a quirky and unforgettable central character.’

Adelaide Advertiser

‘Excellent…a light and lovely story that champions being different in a world where being different is treated with suspicion…Jordan strikes a fabulous blow for resolute individuality.’

Sunday Telegraph

‘This novel is energised by Grace’s grumpy, funny, obsessive, fearful and insightful voice. Her strangeness is beautifully crafted…A winning love story, a sorbet for tired souls.’ Michael McGirr,

Age

‘Smart and sassy, cool and seductive…An explosive new novel from a writer destined to make her mark on the Australian literary scene.’

Brisbane Affair

‘Lashings of spot-on satire.’

Australian Book Review

‘Brimming with sarcastic humour.’

Guardian

‘Curiously compulsive and often highly amusing…an interesting, funny and engaging debut novel.’

Harper’s Bazaar

‘An empathetic journey, both heartbreaking and hilarious.’

Good Reading

‘Fizzes and sparkles…It is, of course, also a love story with a happy ending, which is one of the most satisfying narrative trajectories there is.’ Kerryn Goldsworthy,

Australian Literary Review

‘Sensuously written, fabulously entertaining and a love story that cuts into the soul, this is a first novel that takes your breath away.’

West Australian

‘Delightful…full of charm and humour. ’

The Press

NZ

‘Bringing a quirky humour and a sympathetic view of diversity to her story, the author sustains the momentum to the end of this engaging romantic comedy.’

The Times

‘An unusual and intriguing novel, written with a very light touch.’

Daily Mail

‘Mature, witty and entertaining.’

Irish Times

‘Gemlike…think

The Curious Incident of the Dog in the

Night-Time

thrown into the world of chick-lit…A smartly written comedy that cheekily suggests recovery may not be for everyone.’

Kirkus Reviews

TONI JORDAN was born in Brisbane in 1966. She has a BSc. in physiology from the University of Queensland and qualifications in marketing and professional writing. She has worked as a sales assistant, molecular biologist, quality control chemist and marketing manager. Toni’s published work includes numerous magazine articles, a short story and a chapter in a medical textbook. She

lives in Melbourne and works as a copywriter.

TONI JORDAN

TEXT PUBLISHING

MELBOURNE AUSTRALIA

The paper used in this book is manufactured only from wood grown in sustainable regrowth forests.

The Text Publishing Company

Swann House

22 William St

Melbourne Victoria 3000

Australia

www.textpublishing.com.au

Copyright © Toni Jordan 2008

All rights reserved. Without limiting the rights under copyright above, no part of this publication shall be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise), without the prior permission of both the copyright owner and the publisher of this book

First published by The Text Publishing Company 2008

This edition 2009

Design by Chong

Typeset in Bembo Book by J & M Typesetting

Printed in Australia by Griffin Press

National Library of Australia

Cataloguing-in-Publication data:

Jordan, Toni.

Addition / author, Toni Jordan.

Melbourne : The Text Publishing Company, 2009.

978 1 921520 27 3 (pbk.)

A823.4

This project has been assisted by the Commonwealth Government through the Australia Council, its arts funding and advisory body.

To Robert Luke Stanley-Turner

Sanx

Contents

It all counts.

Not long after the accident, I turned at the gate on my way to school one morning and looked back at the front stairs. There were only ten—normal-looking grey concrete, not like the twenty-two treacherous wooden steps at the back. The front stairs had a small set of lines and some grey sand set in the middle so you wouldn’t slip in bad weather. Somehow it seemed wrong to have walked down them unawares. I felt bad about it. Ungrateful to those stairs that had borne my weight uncomplaining for all of my eight years. I walked back to the stairs and climbed to the top. Then I started down again but this time I counted each one. There. 10.

The day went on but I couldn’t stop thinking about those 10 stairs. Not obsessing. Nothing that kept me from schoolwork or skipping or talking, but a gentle teasing like the way your tongue is drawn to a loose front tooth. On the way home it seemed natural to count my steps from the school gate, down the path, over the footpath, across the road, along the street at the bottom of the hill, across another road, up the hill and then into our yard: 2827.

A lot of steps for so short a distance, but I was smaller then. I’d like to do that walk again now that I’m 172 centimetres instead of 120, and I might one day. I can only remember lying in bed at the end of that first day, triumphant. I had measured the dimensions of my world, and I knew them, and now no one could change them.

Unlike the weather, in Melbourne. 36 degrees and sunny; 38 the same; 36 the same; 12 and raining so hard I risk concussion getting the mail. This January has been like that, so far. When I was a kid I could hardly stand it. From the age of eight I graphed each day’s max and min from the newspapers, desperate for a pattern.

In time, counting became the scaffolding of my life. What’s the best way to stop nonchalantly, so as not to arouse suspicion should someone interrupt? It’s okay to stop, it doesn’t break the rules—the numbers are patient and will wait, provided you don’t forget where you are up to or take an extra pace. But whatever you do, don’t lose count or you’ll have to start again. It’s hard to stop the involuntary twitching, though.

‘Grace, why are your fingers moving like that?’

‘Like what?’

Funny how I sensed this wasn’t something to be discussed with other people, even when I was eight.

The numbers were a secret that belonged only to me. Some kids didn’t even know the length of the school or their house, much less the number of letters in their own name. I am a 19: Grace Lisa Vandenburg. Jill is a 20: Jill Stella Vandenburg, one more than me despite being three years younger. My mother is a 22: Marjorie Anne Vandenburg. My father was a 19 too: James Clay Vandenburg.

Tens began to resonate. Why do things almost always end in zeros? Crossing a road was 30. From the front fence to the shop was 870. Was I subconsciously decimalising my count? Did I stop at the shop’s doormat, rather than the door, so it would end in a zero?

Zeros. Tens. Fingers, toes. The way we name the numbers, in blocks. One day in maths we learnt rounding, changing a number to the nearest one divisible by 10. I asked Mrs Doyle the word for moving a number to the nearest divisible by 7. She didn’t know what I meant.

Why are clocks so obviously wrong? Counting on a base of 60 is a pagan tendency. Why do people tolerate it?

By the time I finished high school I knew about the digital system and its Hindu-Arabic history and the role of the Fibonacci in gaining support for base 10 in 1202. There’s still anger out there in cyberspace—flat-earthers upset that base 10 was chosen over base 12, which they consider purer: easy to halve and quarter, the number of the months and of the apostles. But to me it’s about the fingers—it’s the way the body’s been designed. No debate.

Realising the world was driven by tens was a beautiful turning point, like someone had given me the key. When tidying my room, I started picking up 10 things. 10 things an hour, 10 things a day. 10 brushes of my hair. 10 grapes from the bunch for little lunch. 10 pages of my book to read before sleep. 10 peas to eat. 10 socks to fold. 10 minutes to shower. 10. Now I could see, not just the dimensions of my world, but the size and shape of everything in it. Defined, clear and in its place.

My Barbie Country Camper was out; my Cuisenaire rods were in. On the outside they don’t look like much. Green plastic box; inside, bits of wood, cut and smoothed, in various sizes and colours. Invented by Georges Cuisenaire, my second favourite inventor, while he was looking for a way to make maths easier for children. I love them, especially the colours. Each rod is a number that corresponds to its length, and each number is a different colour. For years into my adult life, numbers were also colours. White was 1. Red was 2. Light green was 3. Pink (a hot, sticky pink) was 4. Yellow was 5. Dark green was 6. Black was 7. Brown was 8. Blue was 9. Orange (although I’d always thought of it as tan, a small vowel shift) was 10.

I spent hours lying on my bed, holding my rods, listening to the

tink

as they knocked together. When I hear that sound I am eight years old again: the bed on a diagonal poking from a corner of the room; easier for my mother to tuck in from both sides. The sheets, flannelette with 34 pastel pink and blue stripes that I counted at night instead of sheep. Along the east wall were 4 dormer windows to catch the morning sun, the 31 slats of the aluminium Venetians pulled high. The bed head had a built-in light behind a translucent plastic screen, and a shelf that held a small transistor radio, untarnished silver in a mock-leather case, a birthday present from my grandfather. There were more shelves on the west wall that held 2 china figurines, a shepherdess and a mermaid, and 3 stuffed Pekinese dogs with long caramel hair that I brushed each night: father, mother and baby. There was a bride doll in a satin gown garnished with 40 pearls. On the floor in the corner were 7 tin cars the size of a child’s fist, left behind after playing.