Acts and Omissions (18 page)

Read Acts and Omissions Online

Authors: Catherine Fox

SEPTEMBER

Chapter 34

In the palace garden the wind wanders down the forbidden laburnum walk. All the gold has fallen. The dry pods whisper:

ssh, ah ssh

!

âWhoa. Wild! That I was not expecting. Seriously, Paul? Whoa.'

Up there on the ceiling a strand of cobweb lifts, falls, lifts. Suze must've missed it. Bible commentaries. Theology. Shelves of it. He can see it all looming there, way up above, over where they ended up.

Here on the carpet.

He hears Paul's breath. There's a catch in it, like a sob.

Ah, shi-i-it. Why does he

have

to be such a whore? When's he gonna learn to say, âNo way, nothing doing,' to the closet cases? Every time he forgets what a big deal it is for them. He's like, âOops, sorr-ee, knocked that vase over there!' And they're all, âOmigod! No! That's priceless Ming dynasty!' Which kind of leaves him thinking, yeah? So another time maybe don't play ball indoors, dude? I mean, c'

mon

.

Freddie shuts his eyes. Gah. Here comes the whole âI'm not gay, I can't believe I let you do that!' thing. Can't we like fast-forward over this part? To the bit where we go, âYeah, we shouldn't've â but know what? Actually, we did.' Followed by the bit where we do it again, and again, because, hey, the Ming's trashed now?

âSo, yeah. That was intense there. Mmm,

mmm

. I'm guessing it's been a while?'

âFreddie, I'm not going to discuss my marriage with you.'

âNaw! Du-

ude

! I mean, since you've been with a guy?'

Nothing.

Outside in the dark he hears a fox wail.

Then it's like he's spilt an icy drink on himself. Oh Jesus.

Please

don't say I'm the first?

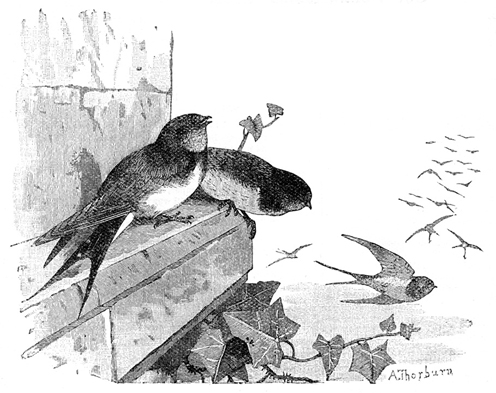

All over the diocese of Lindchester life goes on. The sun sets, it rises. Lives begin, lives end in Lindford General Hospital. Lawns are mown. New school uniform is bought. People put the bins out. Up above, planes slide across the blue. Food banks feed the desperate families who are counting the days till school breakfast club starts again. Clouds still billow from the Cardingforth cloud factory. Swallows congregate on wires, apples ripen and fall ungathered along railway embankments.

Yes, life goes on as though nothing has happened in the palace. Can we pretend nothing has? Can we pick up the pieces, glue them together again? Put the vase back on the shelf and say nothing? Hope nobody notices?

The following morning, the archdeacon â all unaware of his bishop's plight â showers, shaves carefully, then dresses in baggy shorts and a polo shirt, sticks his porkpie hat on and drives out to the pub where he has agreed to meet his . . . date? Is that the word for Dr R? What is the right vocabulary for this, when you're middle-aged? Middle-aged! He feels like a fourteen-year-old! Nudging his friend and daring him to go and say, âMy mate says to tell your mate he fancies her.'

Nobody looking at the big sunshiny man in his little car would guess at the freak adolescent storms tearing across his inner landscape.

Likewise, Jane is in a bit of a stew. What price your feminism now, Dr Rossiter? The bed is heaped with every garment she owns â tried on, then flung aside for the crime of making her feel fat. Now she regrets her snooty resolve not to grace the . . . date? occasion? date (was it a date?) with a new outfit. Fa-a-ark. Now what? Get the legs out, maybe? Black T-shirt dress? Denim skirt? But that will involve some urgent shin topiary. Time for the (yikes!) ancient epilator? No, shaving's less painful. Does she have any razors, though? And what about her moustache?

Shut up, you silly mare. How come you're even having this conversation with yourself? Where will this madness end? With a Brazilian? Oh lordy, lordy, do blokes expect that nowadays? Not the middle-aged ones, surely? No, middle-aged blokes are probably still perfectly happy with your basic traditional lady-sporran. Unless they watch a lot of porn. Which archdeacons don't, presumably.

Or do they?

Will you shut up? We're talking about a walk and a pub lunch, not a dirty weekend, for God's sake.

Anyway, forget the skirt: lardy pallid legs, and no skirt-appropriate summer footwear. Still too sunny for boots, more's the pity. If only it were autumn! Fall, leaves, fall! Die, flowers, away! True, the youngsters all seem to wear trainers with frocks, but Jane knows she'll feel like a mad woman if she tries. She could go the whole hog, get a plaid shopping trolley, a fleece with cats on, and about two hundred badges on her lapels to pull the look together. Not an ensemble famed for its sex appeal, however. So maybeâ

Shit!

The time!

Khaki linen trousers, black top, big silver jewellery, film-star sunnies. It'll have to do. She bangs the door shut and leaps into her car and drives to the canal-side pub where the archdeacon is already parked and waiting under a fig tree, like an Israelite in whom there is no guile.

Shall we tag along?

Matt was the veteran of too many sharings of the Peace to be fazed by Jane's greeting. She'd decided in the car: a peck on the cheek. No, both cheeks. Suavely, insouciantly, in the French manner.

She negotiated the first side successfully, but then bumped jaws, noses. How hard, how indescribably hard it is to be English! Simply

garstly

. Jane's mood veered towards hysterical as she finally landed a peck on his other cheek.

âYou've shaved! I haven't. That's why I'm in me kecks.' She plucked at her trouser thighs as if she was about to curtsey to him. âI was thinking about shaving, but I've run out of razors, and I couldn't bring myself to use the mother-plucker. Sorry, too much information?'

âMother-plucker?'

âEpilator. It's what Danny calls it.'

âAh! And Danny is?'

âMy son. Currently in New Zealand with his dad. But don't ask me about him, or I'll cry.'

Not surprisingly, a silence followed this embargo.

âSo,' said Jane. âWhat's your view on Brazilians?'

Equally unsurprisingly, there was another silence. I've gone completely mad, she thought.

âWell,' said Matt, âI'm an admirer of their free-flowing fast-paced style of football.'

âOf course you are. OK, I'm shutting up now.'

He smiled, and began ambling along the towpath, hands in pockets. After a couple of paces he crooked an elbow at her. She slid her arm through his. They walked in silence. A narrow boat puttered by trailing a cloud of blue smoke.

We're stepping out! I'm stepping out with an archdeacon! Arm-in-arm!

Cabbage whites lolloped round a purple buddleia. She could smell the dank water, a whiff straight from childhood. Long nature walks with Mum. Their version of a summer holiday, because there was no money to go away anywhere. Mum dinning the names of plants into Jane's head, Jane mulishly refusing to respond.

Still knew all the names, though. Dock. Deadly nightshade. Rowan. And that there was a hazelnut tree. She bit her tongue to stop herself bombarding him with botanical erudition. Why wasn't he saying anything? Argh. She glanced up at him and he smiled again.

Relax! It's called companionable silence. He hasn't throttled you and shoved you in the canal yet, so let's assume he likes you.

The opposite bank was a haze of pink, where puffs of willowherb seed crowded a field edge. A half-built house stood among nettles. They passed back gardens with neat lawns. A hammock slung between apple trees. Idyllic. Jane remembered how she'd almost bought a tiny canal-side cottage back when Danny was on the way. But someone had pointed out that she'd never relax: toddler, deep water. So she'd bought the house on Sunningdale Drive instead.

She could move now, though, couldn't she? Start over anywhere she liked. Her world no longer bristled with sharp edges and sudden drops. Blind cords! Toppling wardrobes! Plastic bags! It was time to decommission the klaxon of maternal alarm. Ah, but even so, it was still a death-trap, this planet of ours.

They passed under a brick bridge. The archdeacon had to duck his head. They emerged into the sun again.

âWe're never more than a phone call away from heartbreak,' she said.

He squeezed her hand with his arm. âNo, we're not.'

She remembered: his wife died. Isn't that what Dominic had said?

âHow's young tarty-pants doing?' he asked.

âA bit pouty. Probably because he couldn't go running. Or dogging, or whatever he gets up to. But anyway, he's mobile again, so I dumped him back on the Hendersons yesterday. Then he's off to Argentina next week for a fortnight. I bullied him into it.'

âGood work, that woman.'

âYep. I should perhaps mention that I'm extremely bossy. What do you say to that, Mr Archdeacon?'

âWhatever you tell me to say, ma'am.'

âIs the correct answer!' She felt him squeeze her hand with his arm again. âSo what does archdeaconing entail?'

âBasically, I'm the bishop's leg-breaker.'

âHa! I'd say Paul's quite capable of doing his own leg-breaking. In his quiet steely way.'

âYou know Paul?'

So Jane ended up confessing her shady religious past.

âShame the Church couldn't keep hold of you,' said Matt.

âGod no! I'd've made a terrible priest! I'd be drunk on

vino sacro

by eleven in the morning, and punching the old ladies. Does this pub do real ale, by the way?'

âYou're a real ale kind of gal?'

âCertainly am.'

He stopped. Laid a hand on his heart. âDr Rossiter, will you marry me and have my children?'

âWell, I've had my tubes tied and I don't believe in marriage, but with those caveats in mind, broadly speaking, yes.'

âPeachy,' said the archdeacon. And kissed her.

Father Dominic is sitting among cardboard boxes in his study. Spragg's Haulage of Lindford are moving him. Of course they are. Clergy who are moving in the diocese of Lindchester are required to get three quotes, one of which must be Spragg's Haulage of Lindford. The diocese will then choose the cheapest. Which will be Spragg's Haulage of Lindford. Old Mr Spragg, young Mr Spragg, and the boy. Dominic is terrified that old Mr Spragg will have a coronary while attempting to lift something. He will be found crushed and lifeless under Dominic's pastel green Smeg fridge. Yet if this is what it will take before the diocese allows its clergy to use Pickfords, then old Mr Spragg will not have died in vain.

He is packing his books himself, because he doesn't trust the Spraggs to do it properly. Young Mr Spragg had looked at all the shelves for a long time, ruminating. In the end he said, âYou've got a lot of books, your reverence.'

Lord, have mercy. How many vicars have you moved in your career? Yes, we do tend to have a lot of books.

His phone rings.

âI'm phoning to let you know how it went.'

âNot listening. La la laâ What?!'

âI said, he asked me to marry him.'

â

No!

Tell me everything!'

So she does.

It's Wednesday morning. The bishop watches in the driver's mirror as Freddie walks away towards the station. Train to Heathrow, plane to Argentina. He will be back briefly in a fortnight to collect his stuff, but Paul has made it clear that he will be out when that happens. Miss Blatherwick will drive him to Barchester. And that will be it.

The vase is back on the shelf. The cellar door is shut.

Paul watches till the shaggy blond head has vanished through the station entrance. There. All done. He pulls away from the drop-off zone and drives home. He's only gone half a mile when he has to stop in a layby.

Thistledown breaks from the clumps and drifts off. The blackberries are ripe. Blond grass heads, blond, blond, bend in the wind. A lorry roars past, rocking the car.

Paul knows he's not having a heart attack. Only last month he underwent a whole barrage of tests in Harley Street at the Church Commissioners' expense. Routine for all senior appointments. So he knows he is in rude good health for a man of fifty-eight.

There is nothing wrong with the bishop's heart.

It's just that it is breaking.

Chapter 35

âSo, who's your new boss going to be, deanissima?' Gene asks Marion. âWho will be the next bishop of Lindchester, when our right-trusty and well-beloved Mary Poppins is translated?'

Marion sighs from behind the

Guardian

. âI've told you, I don't know. The process won't even start until his move's announced. And then it'll take ages because of all the baby-boomers retiring. There's a backlog.'

âA backlog of bishops! Is that the proper collective noun? Sounds rather rude. Backlog. Or is that just me?'

âIt's just you, Gene.'

âBut will you have the power to veto any mad homophobic Evanjellybabies they try to appoint?'

âI'll almost certainly be on the Crown Nominations Commission. I can make my feelings known.'

âAnd if we translate that out of cathedral circumbendibus into English, does it mean “You bet your ass! I'm gonna veto the shit out of them!”?' The dean makes no reply. âIt still grieves me that you can't be the next bishop. I quite fancy playing bishop's wife. My first act of hospitality would be a cleansing ritual; an exorcism, if you will. I'd give the entire palace over to an epic three-day homosexual orgy.'

âYou do womble on sometimes, darling. I'm actually trying to read the paper here.'

âThere will be no more triple choc chip muffins in my glorious reign! I piss upon lemon drizzle cake! Ooh. Unfortunate visual. I will never regard lemon drizzle cake in the same light again. Well, never mind: when I preside in the palace, it will be all foie gras and fat juicy ortolans, served by naked altar boys. And filthy innuendo will be our lingua franca. Touch wood. Fnurr fnurr.'

The dean lowers her paper and gives him a headmistressy stare. âIncredible. I never thought this possible, but you've just succeeded in making me glad that the women bishops measure failed to get through Synod.'

Gene bows. âI am but your motley fool, my lady.'

Even as Gene is speaking, the smell of triple choc chip muffins fills the palace. Susanna is back home from her grandmothering duties. She is not a stupid woman. She noticed at once that there was something different about her husband. He looked . . . not quite himself. Younger, somehow. Had something happened to him? What could have happened to him?

Suddenly, she freezes, measuring jug in hand. The truth bursts upon her.

He's trimmed his eyebrows! Susanna smiles and heats the cream to make the chocolate ganache icing. Finally! Aren't men funny? It must be ten years since she ventured a little hint that his eyebrows were getting a bit bushy. And she'd got the distinct message to back off. As far as Paul was concerned, she could fill the palace with her cushions and rose-petal potpourri, but his eyebrows were his own. A last bastion of undomesticated masculinity. Like a shed. Bless him!

I invite my readers to say âAmen' here, even if so far they have not warmed to Paul Henderson. Bless him now, in all his anguish. Despite his new metrosexual eyebrows the poor bishop is wrestling to subdue himself to the world of afternoon tea, with its bone china and petits fours. He must remember to sip and crook his little finger again and use the silver sugar tongs. Not easy, after those nights of mindless gluttony in the Freddie May eat-all-you-can carvery.

Outwardly he seems calm, but Paul is wandering in the smoking ruins of his soul's city. He's numb with disbelief at the Total. Sudden. Breakdown in law and order. His head still roars with the avenging mob. Roiling through his streets, sacking treasuries, torching libraries, profaning every altar.

How could he be so

stupid

?

At least he has some perspective: he's nobody special. He knows he is not the first middle-aged man to make a fool of himself over a pretty blond. He will not be the last. It happens all the time.

But ah, dear God, this is the first time it has happened to

him

!

And it must be the last. Get the army in. Curfews. Crackdowns. Go and sin no more.

You may be wondering, reader, what on earth he is playing at. Really, bishop? You are seriously proposing to sweep this under the vestry carpet? You think you can say a quick sorry to God, then proceed, without further reflection, to the archiepiscopacy of York?

You may be sure he doesn't think this. I don't believe there is a man in the Church of England today who keeps shorter accounts with God. Yes, he is currently shielding Susanna, but Paul is by no means trying to pretend nothing's happened. I would say he's temporarily paralysed. He cannot see what the godly course of action is, how to get out of this mess he has brought upon himself â and potentially on his family, his friends, the whole Church.

Can he trust Freddie's promise of silence? (âDude, I so wouldn't do that to you! And hello? â you think I want the tabloids all over my past?') Oh, but maybe it would be a relief to be exposed, a severe mercy? Or must he bear this alone until his dying day? Hypocrisy! Martyrdom? If not silence, then who ought he to confess to? And what â dear God! â what

is

he now? What does it all mean? Well, whatever else he is, he's an adulterer. And betrayer of a vulnerable young man in his care. He has violated every pastoral trust. He's just the latest in a line of predatory older men in Freddie's life, isn't he?

Only one thing is clear at present: he must not panic and do what can't be undone afterwards, just in order to assuage this terrible guilt.

So never fear, reader. A lifelong habit of inward scrutiny will not permit the bishop to shrug this one off. As it happens, he had already planned a retreat to prepare for the next stage of his ministry. It has been in his diary for months. He will use those ten days in self-examination. He will hold that magnifying glass unflinchingly, focus the rays of truth on himself till sin and pride and self-deception are all burnt out.

And he will

not

indulge in thoughts of him. Ever. Will not linger over peeled-down garments, snagged breath â âOh yeah, Paul, that's it, oh yeah, ohh yeah' â nor consult ever again the compendium of acts committed; nor trail his finger down the inventory of sinews, of clefts, parted lips, limbs, each scar and freckle, pierced flesh and tongue, tattoos, he'll never retrace those serpent coilsâ

Eden

â

Oh God, help me, help me, I can'tâ Because who's he in bed with now?

Whose hands, mouthâ?

Ever again.

Old Mr Spragg, young Mr Spragg and the boy stand on Father Dominic's drive and scratch their heads. How are they going to fit it all in? It's a puzzle, all right.

Dominic (in his Marigolds) watches them through the kitchen window. He despairs. He honestly despairs. How many times did he say, âThis is the kettle. Don't pack it, or you won't be getting any more tea. Kettle. Not to be packed. OK?'

âOoh, right you are, your reverence.'

And where is the kettle?

âOoh, I don't rightly know, your reverence. Maybe we've packed it.'

Take me now, Lord. I'm ready to die.

Jane is stripping the spare bed ready for Dominic. Tomorrow she's going to help him move into his new vicarage. They'll make a good team. She'll just crack on and unpack his boxes, get stuff on shelves and into cupboards, and leave him to stress over where to put his Philippe Starck lemon squeezer.

Jane is hardly the most scrupulous of hostesses, but even she can see that fresh sheets would be polite. She flings the window wide so that poor Dominic will not be tormented by any lingering pheromones, bundles the bed linen under an arm, then scoops up the wastepaper basket with her free hand. Pair of knackered flip-flops on top, but she is not about to investigate further. She hopes to God Freddie remembered to check under the bed for any stray underpants. Et cetera.

Outside in the alley Jane up-ends the basket into the wheelie bin. The rowan berries are red, red, red. Autumn! Boots and jumpers! Huzzah! She's spent almost all her life locked into the rhythms of academe. September always feels like New Year, the season of fresh hopes, when her fancy turns lightly to the thought of love. And now she smiles at the thought of her big bald archdeacon, who is taking her to the pictures on Sunday evening. She's paying her own way, of course, but he has promised to buy the popcorn.

She goes back indoors and stuffs the sheets into the washing machine. A twinge of anxiety: they smell of Freddie. Silly mare. But in all fairness, the boy is fatally easy to love. Like a radioactive bush baby. Well, he's off her hands now. Let his real mum do a shift in the boiler room of maternal angst.

Jane goes upstairs and makes the bed, then squirts a spot of polish into the air to create the impression that dusting has occurred. She wipes her sleeve over the bedside cabinet to protect the impressionable Dominic from the stray skin cells of Freddie May, who by now must be halfway across Patagonia on horseback, or whatever. Well, let's hope he finds that smoking hot retired polo player to look after him from this time forth and for evermore.

But is anything ever going to be that simple for Freddie May? Just stay safe, you bad boy. And my own bad boy, down under, you stay safe too. Keep wearing that crash helmet. And your bad boy dad, he needs to stay safe as well. Oh, in fact, stay safe, you bad boys everywhere.

Would you look at that? It's almost as though she's praying again after all these years. She rolls her eyes, and goes downstairs to stick a bottle of prosecco in the fridge for when Dom arrives.

I'm not coping. I'm just not coping, thinks poor Becky Rogers. She has just screamed at Leah â in public, in the middle of Clark's shoe shop in Lindford.

âRight! That's

it

! You're going to school barefoot!' And yanked her out of the shop by her arm. Past all the people staring. Smirking. Looking sympathetic.

She's sitting in the car in the multi-storey car park weeping. Howling.

Leah kicks the dashboard. Sighs. Can we go now? Kick. Kick. Stop crying, you baby. Kick. Kick. But Mummy carries on crying. She's got snot and everything.

Then Leah has a horrible thought, icy cold. What if she never stops? What if she is having mental health issues? What if she gets out of the car and runs off and leaves Leah on her own?

Like those nightmares she gets. The grown-ups leave her and Jess alone in the car and the car drives off by itself, and Leah doesn't know how to make it stop because she doesn't know how to drive. She's only a child! How can she possibly control the car when she doesn't know how to drive? But she has to, she has to climb into the front and steer it, or the car will crash and she and Jessie will get killed. Jessie starts screaming, âStop the car, stop the car, Leah! Mummy's gone, Daddy's gone!' But it speeds up and speeds up!

This is like the dream, only she can't make herself wake up, because it's real.

âI can't cope, oh, I can't cope, I can't cope!'

Stop saying that! You're the grown-up, you

have

to cope!

âI just can't cope!'

âI'll have the stupid shoes, OK?' she shouts. â

I don't care,I'll have the shoes!

'

âOh, I just can't cope any more!'

Leah opens the glove compartment and grabs the tissues they keep for when Jess is car sick. She shoves them at Mum. âHere.' Nudges her arm. Bangs her arm. â

Here!

'

âThanks, darling.' Mummy wipes the snot off, then blows her nose and wipes her eyes. âOh God, I'm so rubbish. It doesn't matter. We can buy the shoes on line. I'm sorry I'm such a rubbish Mum.'

âYou're not rubbish.'

Is it OK again? Is it? She tries to think of something to add. Probably she should say sorry. But she hates saying it. Teachers and Brown Owl are forever trying to make her say it. âSay it properly, young lady. Like you mean it.'

Mummy starts the car up and they drive home. Leah whispers it in her head all the way. Over and over.

Sorry. Sorry. Sorry.

Each time they pass a street light she says it inside her head.

There's a broken feeling in her throat, like she's fractured her voice-box. That can actually happen. It's been scientifically proved that you can fracture your throat, she might have read it on Wiki; so you have to be really careful and conserve your voice energy. Or she'd say it out loud, probably.