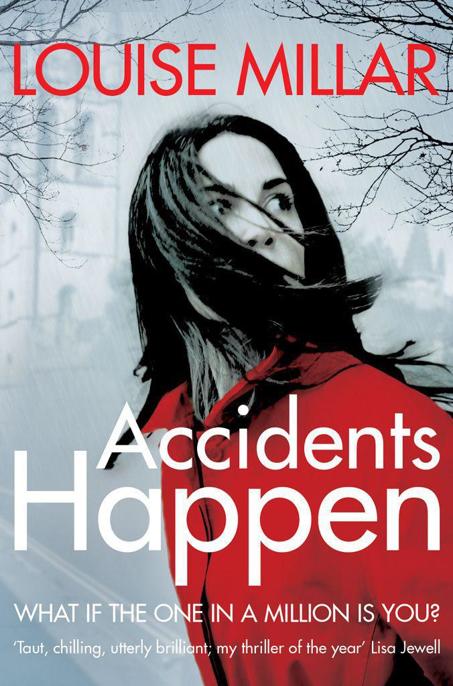

Accidents Happen

Authors: Louise Millar

Tags: #Fiction, #General, #Thrillers, #Psychological

To my husband, with all my love

Contents

In 1962 music teacher Frano Selak from Croatia was a passenger aboard a train that derailed and crashed into a river.

In 1963 he was blown out of the door of the first plane he’d ever flown on, and landed on a haystack.

In 1966 a bus he was travelling on crashed into a river.

In 1970 Frano Selak’s car caught fire as he was driving on a motorway. He escaped just before it exploded.

In 1973 his car caught fire again in a freak accident, burning away most of his hair.

In 1995 Frano Selak was hit by a bus.

In 1996 he met a truck head-on on a mountain road, and his car crashed down a 300-foot precipice.

Frano Selak survived it all.

Then won the lottery.

When the child woke that Sunday morning, the thing was simply there, beside the window, as if it had always been. It had arrived during the night without sound, without fanfare. It had crept quietly between the rocking horse with its red saddle that Granddad had carved from hickory, and yesterday’s clothes, discarded in a pile, the wet clay from the wooded hills outside the house now caked hard along the seams.

It slithered, jagged and full of threat, past the small shelf unit with the rows of books and the snowdome of a mountain, past the cuckoo clock Aunt Nelly brought back from Austria.

The child blinked hard.

Perhaps it was just a shadow, thrown by the flat morning light seeping under the drawn bedroom curtains?

A piece of jumper or a trouser leg, twisted freakishly?

Two blinks, three blinks – and open . . .

No. It was real. Bigger than last time. Angrier, even, with a gaping mouth. A slice of light across the eiderdown from a gap in the curtains pointed straight at it like a dagger. The air in the bedroom felt chill.

Gripping the eiderdown, the child looked around. The clock said 6.34 a.m. Nobody would be up yet. There was time, at least, to think.

The child emerged slowly from the warm sheets, slipped onto the ground and stayed low, as if the thing were about to attack.

It seemed to grow as the child edged nearer. Until it was right there, face to face, spitting out its cool poison.

The child inhaled heavily. It was so much bigger than last time. It jaws gaped, revealing a tiny white spot within its depths. Where the poison came from.

That was new. The tiny white spot.

Without planning to, the child simply didn’t exhale again. It seemed to help for a moment, to hold the breath inside, as if controlling time. If there was no breath, no seconds counted away, time would stop, wouldn’t it?

Nothing would happen.

Mother would not see it.

The clock ticked into the silence of the room. Out here on the hill, a mile from the nearest road, there was nothing else to hear.

Ten, eleven, twelve, thirt—

It was no use. The child’s lungs protested.

Releasing the breath in a panic, the child ran to the half-open bedroom door and peeked one eye around the door frame.

The hall was still. The light along it receded until the kitchen door at the far end was just a blurred shadow. Three doors down, Mother’s door was firmly shut. A gentle snoring from the small room next door to it confirmed Father was not in there with her.

The child desperately looked ahead out of the feature window that ran the breadth of the long, one-storey chalet. Father had said the window was there because people thought the view of the peaks beyond was pretty. That people would envy their family this incredible position.

They didn’t have to live here.

The urge to run out of the front door to hide in the woods was tempered only by the fear of the woods themselves. The dark hollows and weaves of branches that liked to suck you in and spin you around until you didn’t know where you were any more.

Moving back into the bedroom, the child shut the door gently.

There had to be something. Anything.

On the floor lay yesterday’s dressing gown.

On an impulse, the child bent down and flung it, as if it were burning hot, over the rocking horse. By tweaking the corners, you could cover most of it. You could trap its chilly poison behind a curtain of flannel.

What choice was there?

Otherwise, today would be like yesterday, but much worse.

CHAPTER ONE

It was one of those days when you didn’t know what was going on. Just that something unexpected had happened. You could tell by the maverick puff of dark grey smoke that hung above the M40 motorway, the kaleidoscope jam of cars glinting under an otherwise blue sky, by the way that the adults craned their necks out of windows to see what was up ahead.

Jack kicked his football boots together in the back seat, feeling carsick.

‘Where are we?’

‘Nearly there. Oh, will you get out of the bloody way! What is wrong with these . . .?’

He glanced up to see his mother glaring in the rear-view mirror. Behind them in the slow lane, a lorry jutted up the back of their car, its engine growling.

‘Him?’

Kate shook her head crossly. ‘He’s right up my back,’ she spat, clicking on her indicator and looking for an empty space in the adjacent lane.

Jack rubbed his face, which was still rubbery and red from running around the football field. The warm May afternoon air that blew in through the window was mucky with exhaust fumes as three thick rows of traffic tried in vain to force their way slowly towards Oxford.

‘I can’t even see his lights now . . .’

A spasm gripped Jack’s stomach. It made the nausea worse. He turned his eyes back to his computer game. ‘Mum, chill out. They probably have sensors or something to tell them when they’re going to hit something.’

‘Do they?’ She waved to a tiny hatchback in the middle lane that was flashing her to move in. ‘What, even the older ones?’

‘Hmm?’ he replied, pressing a button.

‘Jack? Even old lorries, like that?’

He shrugged. ‘I don’t know. I mean, they don’t

want

to hit you, Mum. They don’t

want

to go to jail.’

Without looking up, he knew she was shaking her head again.

‘Yeah, well, it’s the one who’s

not

thinking that you’ve got to worry about, Jack. Last year, a British couple got killed by a French lorry doing the same thing – he was texting someone in a traffic jam and ran right over them. He didn’t even know he’d done it, they were so squashed.’

‘You told me,’ Jack muttered. He flicked the little man back and forwards, trying to get to the next level, trying to take his mind off his stomach.

‘Oh God – I’m going to be late,’ his mother said, looking at the car clock.

‘What for?’

She hesitated. ‘Just this thing at six.’

‘What, the doctor’s?’

‘No. A work thing.’

He glanced at her in the mirror. Her voice did that thing again, like when she told him the reason she went to London last week on the train. It went flat and calm, as if she were forcing it to stay still. There were no ups and downs in it. And her eyes slid a tiny bit off to the side, as if she were looking at him but not.

A flicker of white caught Jack’s attention in the side mirror. The offending lorry was indicating to move in behind their car again.

He watched his mother, waiting for her to see it. His stomach cramped even worse.

Perhaps it was the cramp that pushed the words out of his mouth.

‘Mum . . .’

‘What?’

He saw her note the lorry’s flashing indicator in the mirror, and her mouth dropped open angrily.

‘Oh Jesus – not again . . . What the . . .?’

Jack banged his football boots together again. Dried mud sprinkled onto the newspaper she’d put down in the back.

‘Mum?’

‘WHAT?’

When his voice came out it was so quiet, he could barely hear it himself over all the straining car engines.

‘I could have come back in the minibus. You could have picked me up at school like everyone else.’

He saw her shoulders jar.

‘It’s fine. I wanted to see you play; it’s the tournament final!’ she said, the shrillness entering her voice again. ‘What, am I an embarrassing mum?’

‘I didn’t say that,’ he said into his computer game.

‘Maybe next time I’ll come wearing my pants on my head.’

She made a silly face at him in the mirror. He smiled, even though he knew that the silly face wasn’t hers. It was stolen property. He’d seen her studying Gabe’s mum when she did it. Gabe’s mum did it a lot, and it made them laugh. When Jack’s mum did it, it was as if the corners of her lips were pulled up by clothes pegs. Then, two minutes later, they’d slip out of the clothes pegs, back to their normal position, where half of her bottom lip was permanently tucked under the top one, kept firmly in place by her teeth; her face set in a grimace that suggested she was concentrating hard on something private.

‘It was nice to see Gabe today,’ she said. ‘Why don’t you ask him round soon?’

Jack kept his eyes on his game. After what she’d done to their house this week, he’d never be able to ask anyone around again.

‘Maybe.’

‘Oh . . . there it is . . . Can you see?’

He leaned over and looked out of the passenger side of the car. There was a flashing blue light around the bend to the left.

‘Police,’ he said, straining forward. ‘And . . . a fire engine.’

‘Really?’

Her voice sounded like splintering glass. He sighed quietly and put down his game.

‘Oh, Mum . . . I’ve got something really good to tell you.’

‘Uhuh?’

‘Next term, Mr Dixon wants me to play reserve for this junior team he runs after school.’

‘Does he?’ She glanced at him. ‘That’s brilliant, Jack . . .’

‘But I’ll have to train on Wednesdays after school, as well, so perhaps I can go to . . .’

In the mirror, he saw her eyes dart wildly back and forward between the blue light and the lorry now crossing lanes to sit behind them again.

His stomach was starting to feel as if it were strung tightly across the middle, like when he tuned the electric guitar Aunt Sass had bought him for Christmas too high to see what would happen.

‘MUM?’

Her eyes darted to him, bewildered.

‘WHAT?’

‘Why don’t you move into the fast lane? Lorries aren’t allowed in there.’

And she’d be further away from the burned-out car that was currently coming into view around the bend on the hard shoulder.

His mother stared at him for a second. Finally, she focused back. Then the clothes-peg smile returned.

‘Good idea, Captain,’ she said brightly. ‘But we’re fine here. Don’t worry about it, Jack.’

He saw her force her eyes to crinkle at the sides, just like Gabe’s mum’s did. Except Gabe’s mum’s eyes were warm and blue, set in furrows of laughter lines and friendly freckles. Jack’s mum’s eyes were still, like amber-coloured glass; they sat in skin as white and smooth as Nana’s china, smudged underneath by dark shadows.

He knew his mum’s extra-crinkly smile was supposed to reassure him that there was nothing to worry about. He was only ten and three-quarter years old, it said. She was the grown-up. She was in charge, and everything was fine.

Jack rubbed his stomach, and watched the lorry in the side mirror.

Oh God. She was so late. She couldn’t miss this appointment. The motorway traffic had concertinaed onto the A40 and now into the city and jammed that up too.