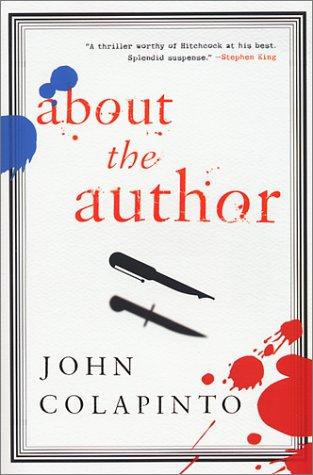

About the Author

Authors: John Colapinto

Tags: #Literature publishing, #Psychological fiction, #Manhattan (New York; N.Y.), #Impostors and Imposture, #General, #Psychological, #Suspense, #Bookstores, #Fiction - Authorship, #Roommates, #Fiction, #Bookstores - Employees, #Murderers

Synopsis:

One of the hottest books of 2001 — A thriller of plagarism and murder as well as a wickedly funny satire on New York

literary world. Cal Cunningham dreams of writing an autobiographical novel that will help him escape from his life as a

penniless bookstore stockboy in upper Manhattan. Yet, after two years of living together, it is Stewart, Cal’s studious

flatmate who has finished writing a page-turning novel — based on Cal’s life. When a timely, fatal bicycle

accident removes Stewart from the scene, Cal appropriates the manuscript as his own and places it in the hands of the

legendarily ferocious literary agent Blackie Yeager. Soon Cal realises his most outlandish fantasies of literary success. That

is, until he discovers that someone knows his secret. For Cal, this means plotting not just his second novel, but also his

first murder.

John Colapinto

and in memory of Jim Cormier

I thought it was time for me to write a novel. I was—what?—twenty-five, twenty-six. Getting to be an old man, as writers go in America

.

—JOHN UPDIKE, in an interview

editor- and agent-extraordinaire, respectively

.

For reasons that will become obvious, I find it difficult to write about Stewart. Well, I find it difficult to write about anything, God knows. But Stewart presents special problems. Do I speak of him as I later came to know him, or as he appeared to me before I learned the truth, before I stripped away the mask of normalcy he hid behind? For so long he seemed nothing but a footnote to my life, a passing reference in what I had imagined would be the story of my swift rise to literary stardom. Today he not only haunts every line of this statement but is, in a sense, its animating spirit, its reason for being.

We were roommates. I moved into Stewart Church’s New York apartment in the fall after my graduation from the University of Minnesota. In his Roommate Wanted ad in the

Village Voice

, he had described himself as a “First-year law student at Columbia University,” and he looked every inch of it: tall and thin, with a doleful, high-cheek-boned face, carroty hair cropped close against the sides of his narrow skull, and greenish eyes that seemed rubbed to dullness from the hours spent scouring the microscopic print of his casebooks. Not that any of this was exactly a bad thing. It was just that Stewart did not fit my initial idea of the kind of person I would end up living with in Manhattan. I was an aspiring author and thus viewed my every action and utterance with an eye to how they would appear when fixed in imperishable print. As such, I considered myself to inhabit a higher plane of existence than people like Stewart. He so clearly belonged to the trudging armies of nonartists, of mere human beings: the workaday drones who live out their unobjectionable lives, then pass, unremembered by all but their immediate families, into oblivion. But then, in a way, Stewart seemed to be

exactly

what I needed in a roommate: a cipher unlikely to distract me from what I thought would be my almost monastic absorption in the pursuit of literature.

Our apartment, a dark one-bedroom on the first floor of a prewar walk-up on West 173rd Street in Washington Heights, was obviously meant for a single occupant, or a childless couple. Both of us were broke at the time—Stewart subsisting on a small scholarship, I toiling for minimum wage as a stockboy at Stodard’s Books in Midtown. And so, with the resourcefulness common to twenty-three-year-olds in our era of diminished expectations, we devised a way to ensure each other a measure of privacy. I slept on a sofabed in the apartment’s front room, an oblong chamber with a dirt-ingrained hardwood floor and chipped wall moldings; Stewart occupied the adjacent bedroom, a space almost identical to mine, with the same view out its windows of the back alley and the fire escapes of the neighboring tenement. The rest of the apartment—a kitchen with small café table, a bathroom crammed with a claw-foot tub and a trickling toilet—was communal.

There are only two conditions under which a pair of straight men can share such quarters: as buddies willing to overlook each other’s peccadilloes, or as respectful strangers willing to stay out of each other’s way. Stewart and I were the latter. Digging his way out from under what seemed an endless avalanche of essays and briefs, Stewart spent his time either shuttered in his room or squirreled away in the stacks of the law library. I, meanwhile, devoted myself to gathering the “material” that I hoped would one day comprise my autobiographical novel.

A word here about the womanizing that became my chief occupation during the two and half years that I lived with Stewart. I was not, in the accepted sense of the term, a sexual predator. For one thing, I was too poor for that. Unlike the double-breasted smoothies who used their gold cards and Rolexes to lure their quarry into cabs, I had nothing but my charm and what I can describe only as my

sincerity

to offer. My looks helped: an inch over six feet tall, panther-thin, with a strongly boned face softened by a tangled mass of black, Byronic locks, I had the kind of appearance that attracted all manner of females, from the lacquered gold diggers who bustled through the aisles of Stodard’s Books to the porcelain-skinned, Amazon-limbed fashion models who slummed in East Village bars. Such women, who are the target of the true pickup artist, were never my first choice. No, it was the funky and bohemian artist girls who made my heart pound, the Cooper Union students with gesso-splattered shoes and Conté-rimmed fingernails who set me dreaming of a soul connection in lonesome New York. That these fierce, independent, talented girls would—after an evening’s talk about books, movies, paintings, music—actually go to

bed

with me seemed, at first, too good to be true. Sure enough, it was. Although they would sleep with me once or twice, such women, I soon learned, had plans and dreams of their own, which emphatically did not include tying themselves down to one man. Again and again my efforts to convert one of these one-night stands into something long-term was met with rebuff. I continued to trawl the bars, but I could no longer kid myself that I was on a quest for permanent love.

I had worried, at first, that Stewart might take exception to the way I was conducting my romantic life. In this, he surprised me. He soon revealed a fascination with my adventures in New York nighttown. He first asked me about them one Sunday morning early in our roommatehood, after he had returned, flushed and sweating, from his weekly bike ride. Initially hesitant to offer up details, in case I might offend what I took to be Stewart’s virginal nature, I simply muttered a few oblique evasions. I soon realized, though, from the direction of his attorneylike questioning, that he wanted the true lowdown. My reclusive roommate was probing for a vicarious taste of

life

. I proceeded to give him a detailed account of my last night’s conquest. Stewart absorbed it all with a tense, hypnotic stare, and when I was through, he quickly excused himself, disappearing into his room to, as he put it, “hit the books”—which I, at the time, assumed was a euphemism for a quite different solitary practice.

So began our sole regular routine as roommates, our one point of social contact: the weekly debriefing sessions. Like Stewart, I came to relish those Sunday-morning performances. I was convinced that my monologues were like “rough drafts” of my New York novel; I fondly imagined that these oral flights were keeping my muse limber and toned against the day when I would repair to the makeshift office I had set up in one corner of the living room and pour my masterpiece onto the page. As for Stewart on those Sunday mornings—when he would throw himself into the chair opposite me across the kitchen table and ask, with an abashed rumble, “Any new Dispatches from Downtown?”—I never once detected anything in him other than a sad and slightly squalid need.

It was on a day several months after our second anniversary as roommates, that the first note of discord entered our relationship. The incident involved a young woman whom I brought home one Saturday evening in the middle of May, shortly after my twenty-fifth birthday.

Some weeks previously, I had resolved to curtail my night crawling (by now I had amassed enough material to fill at least two novels), so that when I visited the Holiday Cocktail Lounge on St. Mark’s Place that Saturday, it was with a mind simply to enjoy a single postwork beer before hurrying home to get cracking, finally, on my novel. That was before a girl, seated just down the bar from me, began to proclaim loudly her talents as a fortune teller. Pale, lank-haired, with a round, dimpled face and a sly, sidelong smile, Les was not one of those girls about whom I could even pretend to have illusions. She seemed friendly and fun, though, with her raucous voice and flirtatious manner—and when, leaning closer and closer to me along the bar, she finally seized my hand and slurred that she wanted to “read my future,” I surrendered my palm and allowed her to peer into it.

“Look,” she cried, bouncing her compact body onto the stool next to me, “you’re gonna be rich, dude!” With an index finger adorned with chipped purple nail polish (and a death’s-head ring), she traced the creases on my palm, a pattern that formed a large M extending from the meaty outside edge of my hand to the web between my thumb and index finger. I’d never noticed it before. “That M stands for money, dude. You’re gonna get a lot. And

soon

!” Perhaps unwisely, I did not grill her on how I would realize this fortune. Instead I inquired, pointedly, about my romantic prospects. She narrowed her eyes. “You know,” she said, “I kinda think I might see something coming up, like, right away.” That more or less did it, and soon I was standing her a series of drinks that she didn’t need and I couldn’t afford—and then it was out onto First Avenue, arm in arm. She had nixed her place, two blocks away (“on account of my roommate’s boyfriend is visiting”), so I offered to foot the cab fare to the Heights.

As usual when I entertained at home, I invited my guest to make herself comfortable on the the living-room sofa bed. I then excused myself and went to the bathroom, pausing in the hall to give a light knuckle-rap on Stewart’s closed bedroom door, a signal we’d long ago devised to indicate that he should confine himself to quarters.

I will refrain from describing, in detail, my couplings with Les, which in most respects were similar, anyway, to the hundred or so other one-night stands that I had conducted over the previous two years. True, I had never before had my erection seized and stroked between the soles of my partner’s bare feet; and I was a little startled when, after I extracted myself from a more conventional erogenous zone, she immediately tumbled me onto my back, stripped off the snakeskin, and sucked up my still-spasming root into her mouth. I mention those acts not to relive them, but rather to convey a sense of historical accuracy, since I’m now convinced that Les’s sexual adventurism pointed to other extremes in her character that I was shortly to learn about. She kept me up, in every sense of the term, until three A.M., whereupon I did not fall asleep so much as drop into a comalike unconsciousness. As usual, the last thing I heard before slipping under was the ever-present, muffled

tippy-tap-tap

of Stewart’s computer through the wall.

Around noon the next day, when Stewart arrived home from his bike ride, I regaled him with my latest Dispatch from Downtown. He listened with his usual absorption, silently chewing at the edge of a fingernail. That is, until the end of the story, when I happened to mention that I had not had the opportunity to speak to the girl in the morning.

He removed the finger from his mouth. “How do you mean?” he asked, frowning.

I replied that I had not seen her leave.

Which was perfectly true. Swimming up into consciousness around eleven o’clock that morning, I had opened my eyes to discover that the space in bed beside me was empty, the covers thrown back to reveal only the faint wrinkle pattern of a body. I had called out for her, then made a quick search of the apartment. Finding it empty, I had concluded that she had simply slipped away without waking me. I wasn’t particularly surprised. No stranger to morning-after misgivings, I had over the years been guilty of a few such sneaky departures myself. Stewart, however, seemed to greet the news with a touch of disapproval.

“You mean she wasn’t even there when you woke up?” he asked, clearly incredulous.

“What of it?” I said, bridling a little at what I took to be the hypocrisy that would allow him to greedily gobble up my tales of debauchery while at the same time looking down his nose at them. “You get used to these things.”

“I guess,” Stewart said, dubiously. Then he glanced at his watch, his usual prelude to announcing that he’d better “hit the books.” I made no attempt to delay him in his dash for the seclusion of his room. He went. But within seconds he was back, standing tensed in the kitchen doorway, an odd look on his face.