Aboard Cabrillo's Galleon (29 page)

Read Aboard Cabrillo's Galleon Online

Authors: Christine Echeverria Bender

Pilot San Remón now stood with Mateo, Manuel, and Cabrillo, his eyes shining brightly. “I never dreamed a pod could be so large, sir!” He gazed all around and laughed. “They encircle all three ships and could easily ring ten!”

The vast number of dolphins amazed even Cabrillo, momentarily easing years from his weathered face. “At times like this I wish I were a merman so I could see what lies under the waves. What it must look like down there, with the total now visible to us multiplied twenty times or more. Imagine swimming right along with this horde! Fetch me my quill and ink, Manuel. I must record this.” Manuel reappeared in moments, and Cabrillo wrote,

“The 16

th

of October has begun as a day of wonder.”

He allowed most of the duties of the morning to be postponed during the quarter of an hour that the dolphins captured the attention of all. His own joy was heightened by the delight of his men, who would undoubtedly weave tales of this moment many times in the years to come. It soon began to seem to him as if the playful creatures actually intended to provide entertainment for him and his crews. It must be that, he mused, or perhaps the dolphins are enthralled by the novelty of the ships, which they view as gigantic but harmless beasts. His quill was kept busy sketching the scene both pictorially and verbally, capturing it as finely and thoroughly as he was able.

Far too soon, and with many a glance following it windward, the pod slipped away to seek a destination known only to its contingent. But the great pleasure the dolphins had given to their human audience during this brief connection lightened both heart and mind for hours.

Not long after the two species had parted, Chumash canoes appeared and came to glide sociably along with the fleet. The sun had just passed its zenith when Cabrillo spied a thickly inhabited harbor where a considerable river emptied into the sea and he ordered the fleet toward it. Sailing nearer, he could see that the river separated two evidently distinct villages, where each settlement layout and home construction differed, some houses possessing gabled roofs rather than the more common domes. With his curiosity highly piqued, he was impatient to settle into a comfortable anchorage and find an explanation.

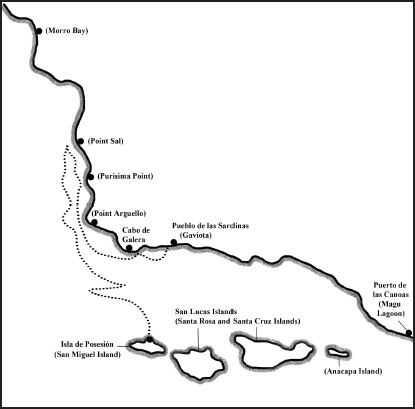

By the time the ships floated sedately at rest and before Cabrillo had a chance to take to his launch, visitors from both villages were arriving and being welcomed aboard. And they didn't come empty-handed. Within a quarter-hour so many loads of fine sardines had been offered in trade that Cabrillo decided to name the place Pueblo de las Sardinas.

After assisting with the initial flurry of goodwill trading and gift distribution Father Lezcano stepped closer to Cabrillo and voiced his surprising conclusion, “Sir, the people from each village have their own diverse language.”

“It seems so to me also, but I hear remnants of the Chumash dialect from each group.”

“Yes, sir, but the words of villagers on the southeastern bank of the river are more familiar to me. Thankfully, their clothing helps to keep them separated for communication.”

As the genial tumult continued on deck, Cabrillo gazed ashore and considered the distinction of habitat, dress, and language in fascination. This was certainly not the first time they'd come upon Indians speaking distinctive languages. On the contrary, they seemed to have discovered a different language, or at least a different dialect, in nearly every village between Pueblo de las Canoas and this place but never within such intimate proximity. How

could

each group cling to a cultural uniqueness while living within a stone's throw from one another? Then again, he considered, perhaps it was not so very unlike some ancient towns in Spain where divergent ethnicities coexisted tolerably well.

He remembered natives they'd met in southern locations telling him repeatedly about wars arising, not uncommonly, between subtribes. Could violent conflicts have contributed to the history of even these two villages? Carefully observing the posturing of both groups and detecting no tensions between them, he concluded that this was unlikely. However, with even the possibility of underlying discord being roused aboard his ships, he quickly organized boarding parties and headed them for the nearest shore. There, he and his delegation began exercising détente in a more structured manner, on one side of the river and then on the other.

Gifts and hospitality proved to be great equalizers. Chiefs of the same stature were honored in the same measure. Trade was divided equally and fairly. By evening, both villages seemed content to have three Spanish ships afloat in their bay.

Although human relations had been kept adequately balanced, to Cabrillo's growing disappointment he had learned little from either clan of new people beside the assertion that farther to the north the natives used much larger canoes. Sitting in his cabin with just his priest, he mused aloud, “Why would northern tribes need larger canoes, Father? To haul larger goods? Perhaps to transport some of those monstrous trees I have been hoping to come across? Or do they use them to travel longer distances out to sea? I hesitate to voice this hope, but perhaps they are needed to cross a stretch of water that reaches China?”

Father Lezcano said, “I sorely wish, sir, that I had been able to make your questions understandable to the Indians. I have provided you with nothing but speculation and hope.”

“The fault is not yours, dear priest. The natives may have no answers to offer even if they understood us well. But this damnable uncertainty of the distance to our goal fires the need to advance without any unnecessary delay.” He cleared his gloomy brow and asked with a lighter expression, “How about a stroll on the quarterdeck? I can listen for signs from nature while you speak with God.”

As he stared up at the twinkling night lights and then out at the endless sheen of ocean he heard only whispered warnings to push ahead.

The day that followed delivered such amiable weather that Cabrillo mentally chastised himself for brooding over imagined omens. The fleet was making good time before fair winds and the only clouds in the brilliant sky were high and widely scattered. His mood continued to lighten as he took closer note of the natives traveling along with the fleet, paddling tirelessly between the many coastal villages they passed. Those bold enough to come aboard were welcomed and rewarded.

To Cabrillo's fascination, one Indian accepted a handful of beads with great solemnity and then proceeded to unwind his waist-length hair and remove a small wooden dagger that had held it in place. He offered the dagger to Cabrillo in two outstretched hands. The captain-general received it with thanks and asked him to demonstrate how he had bound his hair. Seeming pleased by the request, the man gathered and twisted his thick hair into a large knot, wrapped it round and round with a long stretch of twine, and used the dagger to secure two sides of this bundle to his scalp just above the nape.

Cabrillo was so impressed by this feat that he presented the elated native with a pouch filled with beads of every color.

After the man had returned to his canoe, Cabrillo said to his pilot and his priest, “By heaven, some of our own men have hair long enough to be bound in such a manner. It might prove not only more convenient but safer under some conditions. And, in case of need, a dagger would always be at hand.”

Pilot San Remón raised a dubious brow but didnât vocally object to even so wild an idea when it came from his commander while on deck.

Father Lezcano, noting the pilot's hesitation, said, “Why, Captain-General, what a splendid idea. My vows allow me only short hair, of course, but the use of twine and daggers by our men with hair, say, something of the length of our good pilot, would be most advantageous.”

San Remón darted a firm stare at Father Lezcano but otherwise refused to acknowledge such taunting, which he felt the ship's priest dispensed too freely and too often in his direction.

Cabrillo successfully hid his amusement at this light dueling between the young men. Yet he didn't seem able to keep from pointing out every new variety of regional dagger he spotted throughout the day. “Look, pilot, this one is so cleverly made of ivory. How finely

this

dagger has been chipped from flint! Did you see the carved images on this wooden blade?” San Remón somehow managed to maintain his diplomatic silence on the subject.

That evening, however, he quietly drew the ship's physician aside and asked him to act as his barber. A short time later the pilot reappeared on deck to reveal that his locks had been shorn to a previously unseen shortness, and Father Lezcano's expression drooped as he muttered, “You have dashed my hopes of ever seeing a Chumash pilot.”

Such lighthearted diversions were unwillingly swept from the captain-general's mind by the coolness in the breeze that greeted him near the end of his night watch. This midnight held winter in its breath. He could not disregard its imminence.

At daybreak the ships pushed up the westward curving coast but the chilly wind discouraged any canoes from offering companionship. With Cabrillo pushing his men to exert considerable effort to gain each mile, the hour of ten found them approaching what he judged to be the westernmost point they must conquer. From their present viewpoint several men voiced the opinion that the cape took on the shape of a galleon, so it was named Galera.

With noon came a strengthening of the wind and frustratingly little forward progress, and Cabrillo started silently formulating many less flattering names for the cape that taunted them. The weather grew fouler still as they pushed on, and he finally gave the order to break out the heavy jackets. Bracing their stances against the whipping drafts, Cabrillo and Pilot San Remón took out an astrolabe to read the sun and attempted to calculate their present latitude. Though gauging the elevation of old Sol as it flitted from behind shifting clouds proved difficult, they concluded at last that their location was now 36° north of the equator. “From here,” said the captain-general, “some questions become more nagging. How much colder will it grow before we can drop southward again? And, how long will we have to endure whatever winter brings?”

For hours they inched along the cape toiling to clear the point that lay a few miles ahead, but the wind mercilessly blasted them back time and again, and the men were growing exhausted. Grudgingly, bitterly giving up every wave they had just conquered, Cabrillo finally accepted that they had no choice but to bow before nature's insistence and turn their ships in retreat. They must head back in the direction of the island they had named San Lucas. He took a strengthening breath before bellowing the order to alter their course into the face of the wind.

As the gale strengthened and the swells rose higher, the fleet turned and flew to the south. Resigned now, Cabrillo kept his eyes peering forward and altered their course to cut through the waves as smoothly as possible. Now, they must find shelter.

When the lookout from

La Victoria

cried out, “Land ahead, sir!” his young voice blew forward to Cabrillo as a shrill wail, and the captain-general's eyes swept the horizon. There, beneath the low swirling clouds in the distance, it waited. Drawing closer, he discovered that what lay before them were two separate islands rather than the one they had presumed from their earlier remoteness. The larger spread east to west, and he quickly estimated it to be twenty miles long; the lesser one, only half that length. He squinted to see the small island more clearly through the whipping air but could tell little.

“We will sail for the smaller island,” Cabrillo shouted to his pilot, shipmaster, and priest. “Pray that she has a snug anchorage.”

Whether in answer to their prayers or because of a turn of fortune, that late afternoon Cabrillo led his ships through a defiantly rocky reef, past a high-backed sentry rock large enough to consume several ships, and into a moderately sized but deeply cut harbor on the north side of the island.

Once the ships had drawn well inside and been tucked up close to the western arcing boundary of the port, the men of all three ships wiped their slickened brows, scanned their short-term home, and gave sincere thanks for the protectiveness offered by the 500-foot ridge-line that surrounded them. Their next immediate thoughts turned to whomever might own the many canoes that dotted the shore. For several moments, not a soul could be seen.

While he, too, was watchful of the beach, Cabrillo let himself take another moment to appreciate the qualities of the bay. Here, the bluster of the wind was cut to little more than a huff, and its cry was muffled to a moan. The harbor allowed the three ships to nestle safely enough but provided little room for wasteful maneuvering. With the tightness of their quarters in mind, and eyeing the sentry rock with wariness, Cabrillo issued the order to lower double anchors for the night.

As the ships were being tied down he saw things starting to move ashore. One native appeared from the protection of a sand dune, and then another, and another. The slowly gathering Indians walked to their canoes but didn't slide them into the water. Showing no eagerness to approach the ships, they stood absorbedly assessing their visitors.