Abberline: The Man Who Hunted Jack the Ripper (34 page)

Read Abberline: The Man Who Hunted Jack the Ripper Online

Authors: Peter Thurgood

On Saturday 8 May 1892, the following article was published in

Cassell’s Saturday Journal

:

There had lately retired from New Scotland Yard on a liberal pension, and much to the regret of his Chief, Dr. Anderson and his colleagues, a Chief Inspector of the Criminal Investigations Department, Mr. F.G. Abberline. No man in the Police Service now alive – except, perhaps Mr. Shore has a greater claim to speak of the changes, which have come about in the force of all departments. During the past thirty years Mr. Abberline has in his career had much experience in uniform and out of it, and his name has been prominently before the public with cases of more than ordinary interest. His all round success is certainly an instance of experience on the beat and at the station desk as a preliminary training to the detective who discharges his duties in civilian, or as the police call them ‘plain clothes’. A man of such intimate acquaintance with the East End as Mr. Abberline naturally found himself recalled to the scene of his former labours when the series of Whitechapel Murders horrified all the world. His knowledge of crime and the people who commit it, is extensive and peculiar. There is no exaggeration in the statement that whenever a robbery or offence against the law has been committed in the district the detective knew where to find his man and, the missing property too. His friendly relations with the shady folk who crowd into the common lodging houses enable him to pursue his investigations connected with the murders with the greatest of certainty, and the facilities afforded him make it clear to his mind that the miscreant was not to be found lurking in a ‘dossers’ kitchen.

On 8 June 1892 Abberline was once again recalled by Scotland Yard. This time it was not to undertake more excruciating detective work, but to invite him to a retirement dinner and presentation on his behalf. The dinner was held at the Three Nuns Hotel on Aldgate High Street. This ceremony was so popular that a large public crowd stood outside the hotel during the ceremony, hoping, perhaps, to get a glimpse of the great detective. The Three Nuns Hotel is also significant because it featured in several incidents related to the Whitechapel murders. The ceremony created so much interest that the

East London Observer

carried an article entitled, ‘Presentation To A Well-Known Detective’. The subheading read: ‘Chief Inspector Abberline Retires from the Service and is the Recipient of a Presentation.’

Sitting at home and pruning the roses in his garden didn’t exactly appeal to Abberline’s temperament, and within a few months he was eagerly looking for fresh employment. He didn’t have to wait too long, for none other than John George Littlechild, who Abberline knew from the Ripper case and now represented the Pinkerton Detective Agency in London, offered Abberline a job in Monte Carlo on behalf of Pinkerton’s/Littlechild.

The casinos in Monte Carlo were experiencing something of a bad patch, with cheating and stealing on a huge scale. There was pressure from outside interests to close the casinos down, but Monte Carlo had some very rich and powerful friends, including Pope Leo XIII, who called for outside help in cleaning up the casinos’ images.

The Pinkerton Agency was brought in with Abberline at the helm, who in turn hired a group of plain-clothed men to infiltrate the customers at the casinos. These men were experts in their field, and could spot card cheats and frauds a mile off. They also watched the staff and made arrests where necessary. Within the first year of Abberline arriving there, the casinos saved enormous amounts of money, which in today’s terms would probably equal between £10 and £20 million a year.

The casinos’ image was also suffering from over 2,000 suicides and murders during a three-year period. Abberline couldn’t personally come up with a remedy to prevent this, but he did suggest an idea which the casinos took up. This was for them to hire a team of men who would be paid to help dispose of the bodies of the dead losers. The casinos took to this idea and corpses were taken to a secret morgue, where they were stored until a sufficient number were in place, and then a steamer would slip into a small harbour nearby and spirit them away to a secret location, where they would be weighted down and dumped at sea. It was estimated that more than 50 per cent of the deaths in Monte Carlo were never heard about by the general public, and that only the staff at the casinos knew the truth.

Although neither Abberline or Littlechild were personally involved in this operation, they did very well for themselves from cleaning up the casinos in general during their three seasons in Monte Carlo; and probably enjoyed vastly enhanced and comfortable retirements from their efforts there.

Abberline only enjoyed three terms in Monte Carlo, but he continued to work for Pinkerton’s for twelve years, taking on various tasks, mostly in England, which earned him an even more considerable reputation than he already had from his years in the police force.

Frederick George Abberline retired again for the final time in 1904 at the age of 61, and bought a house with his wife at 195 Holdenhurst Road in the seaside town of Bournemouth, where he actually did tend the roses and the lawn. Retirement had finally caught up with the ex-chief inspector.

Frederick George Abberline died in his Bournemouth house on 10 December 1929, at the age of 86. He was buried in an unmarked grave at Wimbourne cemetery, which was the same cemetery where the Ripper suspect Montague Druitt was buried. Abberline’s wife survived him by one year.

Abberline is today commemorated by a blue plaque, which was unveiled on Saturday 29 September 2001, by John Grieve, the Deputy Assistant Commissioner of the Metropolitan Police. The plaque is on the house in Bournemouth where Abberline spent his final years. The plaque was unveiled in the presence of His Worship, the Mayor of Bournemouth.

Inspector Frederick George Abberline, taken from a group photograph of H Division at Leman Street police station in London

c

. 1886. (Wikimedia Commons)

Caricature of Lord Arthur Somerset, taken from

Vanity Fair

, 19 November 1887. (Wikimedia Commons)

Prince Albert Victor. (Wikimedia Commons)

A sketch of Charles Hammond. (Author’s collection)

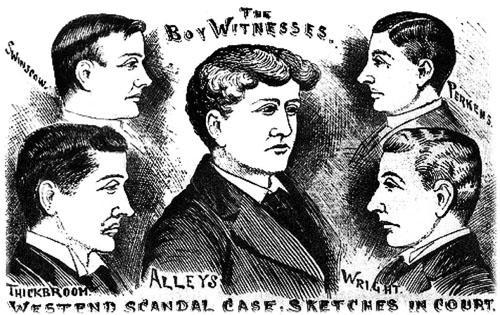

A sketch of the boy witnesses appearing in court to testify against Hammond. (Author’s collection)

Chief Inspector Donald Swanson, the man in charge of the Whitechapel murders investigation,

c.

1920. (The Swanson family)