A Young Man's Passage (17 page)

Read A Young Man's Passage Online

Authors: Julian Clary

My mind wandered and I started to think about finding homes for the little darlings. After all, they couldn’t stay at home with Fanny and me for ever. They had their own lives to lead. There was a big, exciting world out there, and the sooner they went off to explore it, the better. It was a bit like having unsavoury relatives to stay: we’d be polite and ensure they had enough to eat and somewhere to sleep, but whenever they were ready for the off, just let us know . . .

I put the word out and stuck a card on the noticeboard at Tesco’s at Westcombe Park. A charming family responded to the ad, came for a viewing and earmarked Harriet. I said she’d cost £5. The set designer from the Covent Garden Community Centre came and chose Molly. The ticket collector at Westcombe Park said his friend at the next station down the line, Maze Hill, wanted a male puppy, so he was promised Wesley. As for Margaret, I can’t remember. Anyway, I knew they all had good homes waiting for them.

At four weeks the puppies couldn’t be contained in my bedroom any longer. I called my parents and probably exaggerated the story a bit. I remember my father came to pick us up within hours, bless him, appearing on my doorstep with a worried expression, half-expecting canine Triffids to be entwined around my every limb.

In Swindon we made the garage into the nursery, or Detention Centre, as it came to be known. They were allowed into the garden each afternoon for several hours’ association. By now they were a formidable pack. Fanny looked on with distaste as they ripped up the lawn, gnawed at shrubs and showed scant regard for the dignity of the rotary washing line.

Wesley once attacked my 18-month-old niece, Sandy, who was wandering about innocently. He ripped her pink frilly dress and made her cry.

I decided they had to go. Some would say six weeks is too early, but not for Fanny and me.

Off they all went one afternoon within a couple of hours. Fanny didn’t so much as glance after them. She gave me look of relief, as if a bad smell attributed to her had finally dissipated and normal service could be resumed. We never heard a word about any of them again. Eventually I stopped scanning the local paper, fearful that Wesley or his sisters had eaten a baby, attacked a pensioner or ripped the face off a postman.

Although still less than a year old, Fanny had a worldly wise air about her now. She hadn’t informed me yet, but she had set her sights on a showbiz life.

UNEMPLOYED AGAIN, I

went along to see Andy Cunningham do his ventriloquist act, ‘Magritte, the Mind-reading Rat’, at a vegetarian restaurant in Highgate called the Earth Exchange. They had cabaret there every Monday night. There was no stage. You just stood in the fireplace and did your turn. You only got paid about £5, but a dinner of brown rice and lentils was yours for the asking. Andy suggested I revive Gillian Pie-Face from the

Winter Draws On!

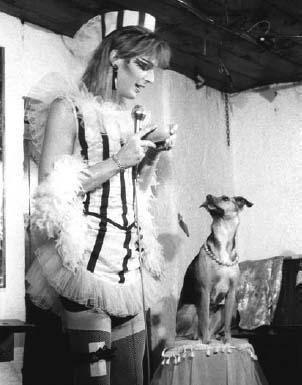

show. He had a word with Kim, who ran the night, and the next week I did the ‘try-out’ spot. Ms Pie-Face, as the name suggests, wasn’t a serious attempt at female impersonation. She wore a black kaftan, plimsolls, a string of wooden beads and a messy blonde wig. Gillian was an agony aunt, here, she explained, ‘to comfort the sick of spirit, the broken-hearted and the world weary.’ I had written most of it with a talented young writer called Chris Stagg.

Stave off that nervous breakdown,

Wipe away that tear,

Shun that emotional crisis

Gillian Pie-Face is here!

I’ve leapt off the page to deal with my public on a one-to-one basis, to get to grips with your problems as no agony aunt has done before, to bathe your wounds with my very own sponge of sympathy . . . and to plug my new book,

Look Before You Leap

, Methuen Press, £7.50 hardback only. Now, before I start the serious business of the evening, namely solving the many and varied little upsets many of you may be harbouring, I’d like to, if I may, read a specimen from my book,

The Milk of Human Kindness

, Faber and Faber Press, £11.99, hardback only. [Opens book.] Ah, yes, here we are . . . it’s from Head-in-the-Oven, of Thornton Heath.

Dear Gillian,

I am beside myself. Six months ago my wife and six children were killed in a plane crash. I cannot tell you how guilty I feel as it was my first time piloting a plane. How we were all looking forward to it, Margery, I and the little ones. I have even turned to God in my despair and often I ask him: ‘Why oh why, God, was there only the one parachute? Will I ever overcome my grief?

Head-in-the-Oven, of Thornton Heath.

And my advice to him was:

Dear Head-in-the-Oven,

Some people need something to be depressed about, and go out of their way to find it. Try to get out more and don’t wait for people to come to you. They won’t. Not if they’ve got any sense.

The conclusion of the act was the laying-on of hands. ‘An uncanny gift I’ve only recently discovered in my possession.’ After a few moments attempting to cure a man in the audience, she said, ‘It’s no good. I’m going to have to plunge you into darkness.’ The kaftan was then thrown over the seated punter, his head at groin level. The effect was of the hapless punter performing oral sex on me behind a curtain. ‘Ah, that’s better!’ said Gillian. ‘I can feel the goodness flowing from my tips . . .’

I was familiar with the material and it didn’t go too badly. Kim booked me for the next week and told me of other possible gigs, at the Crown and Castle in Dalston, the Hemingford Arms in Islington and the Pindar of Wakefield in Kings Cross. The alternative cabaret circuit was in its infancy, mostly small rooms above pubs. Three or four acts and a compère performed in front of their friends and a few supply-teacher types, then split the proceedings among themselves. I phoned round and got a few more try-out spots.

Meanwhile, I had some modelling shots done for an agency, and continued to apply unsuccessfully for acting jobs.

THE FARNDALE AVENUE

Housing Estate Townswomen’s Guild’s Amateur Dramatic Society was in reality a company called Entertainment Machine run by a worried-looking man called David McGillivray. Their particular niche was the excruciating but hilarious world of amateur dramatics, where sets fell down, incompetent actors forgot their lines and the raffle was more important than the plot. Janet Sate, an actress I’d worked and bonded with at Covent Garden, was on tour in 1982 with their French farce,

Chase Me Up Farndale Avenue, S’il Vous Plaît!

The actress playing Mrs Reece was so dire I was smuggled in to rehearse in secret for a couple of days before she was given the boot and I took over.

Mrs Phoebe Reece was the chairperson of the dramatic society and took her role very seriously, interrupting the play to recall past productions: ‘More senior members amongst you will recall with pleasure I expect such extravaganzas as

A Woman’s Mission

,

Cave Girls, It’s Miss Wimbush!

and, of course, our big success,

Brown Owl Pulls It Off

.’ She also announced, ‘After a very heated committee meeting, we’ve decided to mount our first bisexual production. It’s high time we gave one or two of our younger actresses the chance to play with a male member. And I’m certainly looking forward to trying my hand at it as well.’

There were a lot of lines to learn and I was far from ready on my first night at the Prince Regent Theatre on the Isle of Wight. Instead of saying, ‘That was a narrow squeak,’ I came up with, ‘That was a short quack.’ I also had a large explanatory speech to reel off in act two which was vital to the plot. My cue came from David, who was playing the part of Gordon. The time came and he said, ‘But what shall we do when we get to the bistro and Mr Barratt isn’t there?’

‘That’s your problem,’ I said, and promptly left the stage.

Despite all this, the theatre manager Brian McDermot was full of praise: ‘Come to the bar and be lionised!’ he said after the show. Over drinks I told him about my Gillian Pie-Face act and he booked me. I accepted his offer to do a full evening’s entertainment despite the fact I still only had 20 minutes’ worth of material. I’d worry about that nearer the time.

David McGillivray, our author and director, seemed to thrive on drama. The tour took us all over the country. The day after my first night on the Isle of Wight we were booked in Irvine in Scotland. Our means of transport – a sad little van for set and actors – broke down in Portsmouth and the AA and British Rail had to pull out all the stops to deliver us in the nick of time. Our performance in Harlech had no business taking place either, when following some hold-up on the Severn Bridge we didn’t arrive there until 7.45 p.m. Wild-eyed and breathless, David explained to the audience that there would be a delay until 9 p.m. if they could possibly bear with us. This being Wales, where there was nothing else to do, they waited. Travel-weary and hungry, we began hauling the set into the theatre past bemused punters. Fortunately I had one of my opportune nosebleeds and could only watch and encourage.

Our accommodation was always cheap and cheerful: nylon sheets and candlewick bedspreads. After a show in Cumbernauld, we sat in the lounge admiring the knick-knacks and making small talk with the landlord. When I offered him a cigarette, he said, ‘No thanks, I’m a pipe.’ Before we retired to our rooms, he asked if we’d like a cooked breakfast in the morning. ‘No thanks,’ I said, ‘I’m a corn flake.’

When the tour finished, I returned to the Isle of Wight to do the one-man show as promised. I cobbled together Gillian, May and Mrs Reece and hoped for the best. It was a disaster, the bemused punters shuffling out in silence after 40 sweaty minutes.

I returned home, back to the dole, the occasional gig at the Earth Exchange my only prospect.

But if work was thin on the ground, men certainly weren’t. They were coming thick and fast.

SIX

‘Say, boys, whatever do you mean, When you wink the other eye?’

‘WINK THE OTHER EYE’ BY GEORGE LE BRUNN AND W.T. LYTTON

I MET A

Boy called Mark one evening on the train home from Charing Cross. He lived just down the road. He had a rugby player’s face and pale, freckled skin. I didn’t fancy him, but he had other attractions. He knew how to enjoy life, and we became sisters, cruising companions and friends. We seemed to go out most nights, but as he was a student and I was on the dole, money was tight.

Here’s how it worked. We’d meet about 9 p.m. at the bus stop on Blackheath, each with a £5 note and no more. The bus stop was just before some traffic lights, and Mark would tap on the passenger window of a waiting car and ask the single male occupant if he was driving into town and could we cadge a lift? Once in town we’d skim through the Soho bars, have a drink if anyone offered to buy us one . . . ‘And this is my friend Julian, he’d like a pint of Grolsch too,’ kind of business. We’d enter Heaven nightclub, our fiver still intact, either with a free entrance voucher from one of the trashy gay mags or because Mark had somehow wangled us onto the guest list. Inside there’d be more shameless cruising for beverages.

As the evening wore on we might be reduced to collecting the dregs of other revellers’ discarded drinks. That’s the horrible truth, pain me though it does to reveal it. I think I even stole the odd glass from those frisky enough to take to the dance floor and leave their refreshments unattended. Cheap, I know, and I’m full of retrospective horror and can only apologise. Then it was Pick-up, especially if he had a car, and one could say goodnight to one’s sister and leave, flourishing the fiver in triumph for good measure.

Far-from-tantric sex inevitably followed. The earth may not have moved very far, but it would round an evening off nicely. Occasionally there would be an encore. A half-hearted attempt at ‘going out’ even, but it would always end in stony silences or unanswered calls.

I was obsessed for a while with a man I’d slept with called Henry. He was posh and whisked me back to his Cadogan Square flat in Chelsea to be ravished. The flat was full of antique furniture, but the sheets were dirty – there was a grey mark on the antique linen pillow where he lay his beautiful head. But Henry wasn’t interested in an encore and didn’t answer my calls. Not good with rejection, even then, I wrote the obligatory poem.

Like the cock on a windless day