A World Lit Only by Fire (19 page)

Read A World Lit Only by Fire Online

Authors: William Manchester

M

EANTIME

, outside monastery walls, the reading public was surging, though not by design. No new literacy programs were introduced,

the educational process continued to be chaotic, and those who received any degree of systematic teaching had to be either

fortunate or unusually persistent. The number of people who were fortunate remained stable. It was persistence, and the number

of schools, which rose. As the presses disgorged new printed matter, the yearning for literacy spread like a fever; millions

of Europeans led their children to classrooms and remained to learn themselves. Typically, a class would be leavened with

women anxious to learn about literature and philosophy, and middle-class adolescents contemplating a career in trade.

Instruction was available in three forms: popular education, apprenticeship, and the courses of study at traditional schools

and universities. Only the first was available to the vast majority, and it is impossible to define because it varied so from

place to place. Two generalizations hold: popular education was confined to colloquial tongues, and it was unambitious. The

teachers themselves knew no Latin; many were barely literate in their native languages. Some gave their services free, beginning

with classes teaching little children their letters; others were poor women eager to make a few pennies. Pupils helped each

other. The curriculum was limited to reading, writing, simple arithmetic, and the catechism. “That a relatively large number

of people knew how to read, write and count,” conclude the authors of

The New Cambridge Modern History

, “was due to the casual and ill-organized efforts of thousands of humble individuals. Such were the uncertain foundations

not only of the popularity of vernacular literature but also of technical advance and the diffusion of general knowledge.”

Apprentices were fewer. The sons of master journeymen were given special consideration; property qualifications were imposed

on outsiders, and the children of peasants and laborers were excluded. In the cruder trades instruction was confined to skills

which were mechanically imitated. But the better crafts went beyond that, teaching accounting, mathematics, and the writing

of commercial letters. This was especially important to merchants—commerce was still regarded as a trade, though dealers

were quickly forming the nucleus of the new middle class—and the sons of merchants led the way in learning foreign languages.

They were already among the most attentive pupils. The growth of industry gave education a new urgency. Literacy had been

an expensive indulgence in an agrarian culture, but in an urban, mercantile world it was mandatory. Higher education, based

on Latin, was another world. Schools concentrated on preparing boys for it, using as fundamental texts Donatus’s grammar for

instruction in Latin and Latin translations of Aristotle.

In 1502 the Holy See had ordered the burning of all books questioning papal authority. It was a futile bull—the velocity

of new ideas continued to pick up momentum—and the Church decided to adopt stronger measures. In 1516, two years after Copernicus

conceived his heretical solution to the riddle of the skies, the Fifth Lateran Council approved

De impressione liborum

, an uncompromising decree which forbade the printing of

any

new volume without the Vatican’s imprimatur.

As a response, that was about as fruitful as the twentieth-century encyclicals of Popes Pius XI and Paul VI rejecting birth

control.

De impressione liborum

was, among other things, too late. The literary Renaissance, dating in England from William Caxton’s edition of Chaucer’s

Canterbury Tales

in 1477, had been under way for a full generation. As the old century merged with the new, the movement pushed forward, fueled

by a torrent of creative energy, by the growing cultivation of individuality among the learned, and by the development of

distinctive literary styles, emerging in force for the first time since the last works of Tacitus, Suetonius, and Marcus Aurelius

had appeared in the second century. The authors, poets, and playwrights of the new era never scaled the heights of Renaissance

artists, but they were starting from lower ground. With a few lonely exceptions—Petrarch’s

De viris illustribus

, Boccaccio’s

Decameron

—medieval Europe’s contributions to world literature had been negligible. Japan had been more productive, and the Stygian

murk of the Dark Ages is reflected in the dismal fact that Christendom had then published nothing matching the eloquence of

the infidel Muhammad in his seventh-century Koran.

In the years bracketing the dawn of the sixteenth century, that began to change. Indeed, considering the high incidence of

illiteracy, a remarkable number of works written or published then have survived as classics.

Le morte d’Arthur

(1495) and

Il principe

(1513) are illustrative, though both authors are misunderstood by modern readers. In the popular imagination Sir Thomas Malory

has been identified with the fictive chivalry of his tales. Actually he was a most unchivalrous knight who led a spectacular

criminal career, which began with attempted murder and moved on to rape, extortion, robbery of churches, theft of deer and

cattle, and promiscuous vandalism. He wrote his most persuasive romances behind bars.

Malory has been spared; Niccolò Machiavelli has been slandered. Machiavelli was a principled Florentine and a gifted observer

of contemporary Italy; his concise

Il principe

reveals profound insight into human nature and an acute grasp of political reality in the scene he saw. Nevertheless, because

of that very book, he has been the victim of a double injustice. Though he was only analyzing his age, later generations have

not only interpreted the work as cynical, unscrupulous, and immoral; they have turned his very name to a pejorative. In fact,

he was a passionate, devout Christian who was appalled by the morality of his age. In an introspective self-portrait he wrote:

Io rido, e rider mio non passa dentro

;

Io ardo, e I’arsion mia non par di fore

.

I laugh, and my laughter is not within me;

I burn, and the burning is not seen outside.

Among the other memorable works of the time were Sebastian Brandt’s

Das Narrenschiff

; Peter Dorland van Diest’s

Elckerlijk

; Guicciardini’s

Storia d’Italia

; Rabelais’s

Pantagruel

; Castiglione’s

Il cortegiano

; Sir Thomas More’s

Utopia

; Philippe de Commines’s

Mémoires

; William Dunbar’s

Dance of the Sevin Deidly Sinnes

; Ludovico Ariosto’s

Orlando Furioso

; Fernando de Rojas’s

La Celestina

; Machiavelli’s

Discorsi sopra la prima deca di Tito Livio

, his penetrating

Dell’arte della guerra

, and his superb comedy,

La Mandragola

; the plays of John Skelton; the poetry of Sir Thomas Wyatt and Henry Howard, earl of Surrey; and all the works of Desiderius

Erasmus, who left his native Holland to roam Europe’s centers of learning and turn out a stream of books, including

Enchiridion militis Christiani

, and

Adagia

, his collection of proverbs.

Scholars—most of whom were theologians—continued to be fluent in classical tongues, but in the new intellectual climate

that was inadequate. Publishers could no longer assume that their customers would be fluent in Latin. In past centuries, when

each country had been a closed society, an author who preferred to write in the vernacular was unknown to those unfamiliar

with it. No more; provincialism had been succeeded by an awareness of

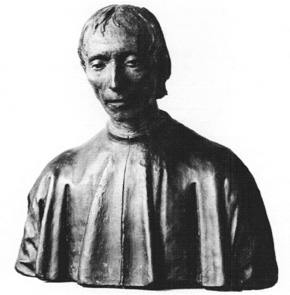

Niccolò Machiavelli (1469–1527)

Europe as a comity of nations, and readers were curious about the work of foreign writers—so much so that translations became

profitable. In England, for example, Brandt’s book appeared as

The Ship of Fools

, Van Diest’s as

Everyman

, Castiglione’s as

The Courtier

, and Machiavelli’s comedy as

The Mandrake

. In 1503 Thomas à Kempis’s

De imitatione Christi

came off London presses as

The Imitation of Christ

. Erasmus’s

Institutio principis Christiani

became available as

The Education of a Christian Prince

, and Hartmann Schedel’s illustrated world history was published simultaneously in Latin and German.

Learned men became linguists. Ambrogio Calepino brought out

Cornucopiae

, the first polyglot dictionary, and the Collegium Trilingue was founded in Louvain. This was followed by publication, at

the University of Alcalá, of a Bible in four tongues: Greek, Latin, Hebrew, and Aramaic. To be sure, none of them was widely

understood in western Europe, but at least the Scriptures could, fifteen centuries after the crucifixion, be read in the language

of Christ himself.

T

HE DAYS WHEN

the Church’s critics could be silenced by intimidating naive peasants, or by putting the torch to defiant apostates, were

ending. There were too many of them; they were too resourceful, intelligent, well organized, and powerfully connected, and

they were far more strongly entrenched than, say, the infidel host the crusaders had attacked. Their strongholds were Europe’s

crowded, quarrelsome, thriving, and above all independent new universities.

Before the Renaissance, Christendom’s higher education had been in hopeless disarray. Some famous institutions had been established,

though their forms and curricula would be almost unrecognizable to members of twentieth-century faculties. Oxford’s earliest

colleges dated from the 1200s; Cambridge had begun to emerge a century later; and for as long as Parisians could remember,

groups of students had been gathering, at one time or another, in this or that

quartier

, on the left bank of the Seine. But they had represented no formidable force in society.

Various chronicles enigmatically note “the beginnings” of universities in scattered medieval communities, among them Bologna,

Salamanca, Montpellier, Kraków, Leipzig, Pisa, Prague, Cologne, and Heidelberg. Precisely what this meant varied from one

to another. We know from Copernicus that there was learning in Kraków. He was fortunate. In most cities, academic activity

had been confined to the issuance of a charter, the drawing up of rough plans, and, where students and professors met at irregular

intervals, heavy emphasis on animism and Scholasticism. Animists believed that every material form of reality possessed a

soul—not only plants and stones, but even such natural phenomena as earthquakes and thunderstorms. Scholastics sought to

replace all forms of philosophy with Catholic theology. Both were shadowy disciplines, but there was worse: the divine right

of sovereigns, for example; astrology; even alchemy; and, late in the period, Ramism.

Within universities, there were no colleges as the term later came to be understood. Selected students lived in halls, but

90 percent of the undergraduates boarded elsewhere. They were governed by peculiar rules: athletics were forbidden, and since

1350 scofflaws at Oxford had been subject to flogging. In theory, classes began at 6

A.M

. and continued until 5

P.M

. In practice most students spent their time elsewhere, often in taverns. As a consequence, hostility between town and gown

was often high; at Oxford one clash, which became known as the Great Slaughter, ended in the deaths of several undergraduates

and townsmen.