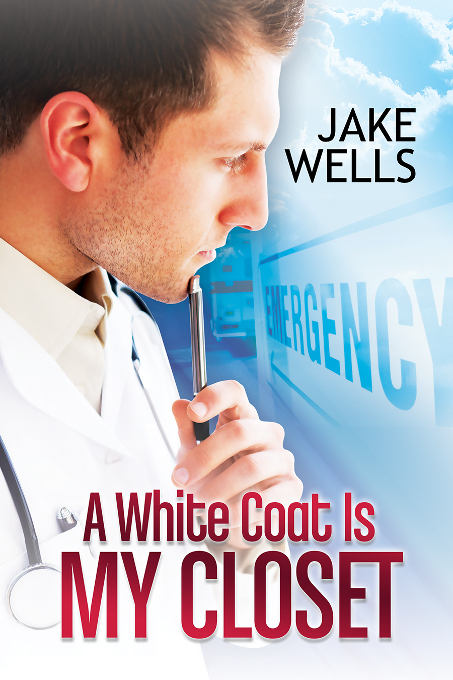

A White Coat Is My Closet

Read A White Coat Is My Closet Online

Authors: Jake Wells

Published by

Dreamspinner Press

5032 Capital Circle SW

Suite 2, PMB# 279

Tallahassee, FL 32305-7886

USA

http://www.dreamspinnerpress.com/

This is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places, and incidents either are the product of author imagination or are used fictitiously, and any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, business establishments, events, or locales is entirely coincidental.

A White Coat Is My Closet

© 2013 Jake Wells.

Cover Art

© 2013 Leah Kaye Suttle.

www.leahsuttle.com

Cover content is for illustrative purposes only and any person depicted on the cover is a model.

All rights reserved. This book is licensed to the original purchaser only. Duplication or distribution via any means is illegal and a violation of international copyright law, subject to criminal prosecution and upon conviction, fines, and/or imprisonment. Any eBook format cannot be legally loaned or given to others. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without the written permission of the Publisher, except where permitted by law. To request permission and all other inquiries, contact Dreamspinner Press, 5032 Capital Circle SW, Suite 2, PMB# 279, Tallahassee, FL 32305-7886, USA, or http://www.dreamspinnerpress.com/.

ISBN: 978-1-62798-256-6

Digital ISBN: 978-1-62798-255-9

Printed in the United States of America

First Edition

October 2013

Completing this book requires me to thank more people than is possible. So for now: to my parents, who have always loved me and to whom I’ll be forever indebted; to my friends, who support me unconditionally; to my partner, who completes me; and to my patients, because they make being a doctor worth it. Finally, this book is also dedicated to the L.A. Gay & Lesbian Center’s Youth Services division. All royalties from the sale of this book will be donated to Youth Services, because sometimes success in life starts with being given a chance.

Thanks!

T

HE

sound of the beeper ripped through the darkness like a bomb going off next to my ear. I sat bolt upright in bed.

“Delivery room six STAT, Delivery room six STAT.” The automated voice cracked an unforgiving, authoritative command.

My feet hit the floor, and I was in motion before I gave it any conscious thought. A STAT call to the delivery room could only mean one thing: a baby was in trouble. Sometimes, even when the monitors attached to the expectant mother gave ominous warnings that something was wrong with the baby, when it was finally born, it could look fine. Other times, the baby’s condition at birth could be critical. In those situations, the decisions I made within the first few minutes could mean the difference between a bouncing, healthy newborn and a train wreck. A moment’s hesitation or a slight error in judgment and a baby could go from having a bright, promising future to being either dead or brain-damaged.

As I raced down the single flight of stairs, taking them two or three at a time, I acknowledged the knot growing in my stomach. I was in my last year of residency in a top-level pediatric training program, but despite all my experience and having intervened in numerous neonatal emergencies, I was still anxious. I never discounted the magnitude of my responsibility. I wasn’t sure I’d ever be able to forgive myself if I thought a mistake I had made resulted in a bad outcome.

I practically sprinted into the central back corridor that connected all the delivery rooms. This area was only accessible to physicians and staff. Each delivery room had two entrances. One entrance was on the outside wall of the delivery room and had a door at least six feet wide, intended for patient use. Hospital beds carrying pregnant women could be easily wheeled through these. On the inside wall of the delivery room was the staff door that opened into the central back corridor. Each of these doors was flanked by a metal sink and cabinets with supplies that had to be immediately accessible. In one sweeping motion, I pulled a scrub cap out of one of the cabinets, secured it over my head, and then tied a surgical mask in place over my nose and mouth.

There was already a flurry of activity when I burst into the delivery room. Several IV bags hung from poles around the head of a woman who lay on an operating table. A quick glance at her expression registered that she was confused and panicked. The anesthesiologist was feverishly drawing up medicines and infusing them into a small tube that disappeared into the middle of the woman’s lower back. Apparently, when the team had anticipated an uneventful, normal delivery, he had given her an epidural with the intent of allowing her to experience the birthing process free of pain. Now he was hoping to utilize the same line to administer higher doses of anesthesia and thus allow the obstetrician to safely perform an emergency caesarian. The IV bags had been primed in the event that this was unsuccessful and he was forced to resort to emergency general anesthesia.

I made my way over to the neonatal resuscitation station, knowing this was where my participation would be essential. The station was kind of a platform on wheels. It consisted of a cushioned pad with both a warmer and a bright halogen light overhead. Its back panel housed various switches and gauges. I connected an infant resuscitation mask to an adapter on the end of some sterile tubing and then attached the other end of the tubing to a valve that delivered oxygen. Knowing that getting oxygen to the baby was going to be my first objective, I turned on the valve and made sure there was a strong flow coming through the mask. As I worked, I caught Fern’s attention and asked her for a quick briefing. Fern was the charge nurse in obstetrics and pretty much ran the show.

She lifted her index finger in a “just a moment” gesture, then unwrapped a package of surgical instruments and, without touching them, dropped them onto a tray. With practiced precision, they landed next to an empty basin and a couple of sterile drapes. Within the next few seconds, one of the drapes would be used to cover the woman’s abdomen and the other hung to provide a barrier between her face and the surgical field. Fern expertly poured an antiseptic scrub into the basin, then stepped back to allow the nurse who was going to be assisting the obstetrician to step into position.

With impressive efficiency, Fern moved to the head of the operating table and leaned over the woman. “Becky,” she said. “Everything is going to be all right. I know this is a little disorienting, but we’re trying to move quickly so we can deliver your baby as fast as possible. We’re almost ready to begin, but before we do, I’ll get your husband. He’ll be by your side for the whole thing. For now, I just want you to take a few deep breaths and trust that you’re in good hands.” She ran her fingers softly across Becky’s forehead in an attempt to offer a little palpable assurance, then turned her attention to me to give me an abbreviated rundown. She spoke in hushed tones to try to minimize Becky’s alarm.

“She was having an uneventful labor when she must have abrupted. There’s a lot of vaginal bleeding and the scalp electrode on the baby shows significant bradycardia. The heart rate has already been down for four minutes.” Bradycardia was medical terminology for a slow heart rate, and the fact that it had already been down for four minutes wasn’t a good sign. Fern glanced over her shoulder at the progress being made in preparing Becky for the surgery.

Dr. Brian Torres, the obstetrician, stealthily pulled on a sterile gown, then pushed his hands into surgical gloves. He barked at the obstetrical resident who had just flown into the room that he would have no time to scrub. “Just throw a gown on and get ready. As soon as I get the go-ahead from Jack that she’s numb, I’m going to cut.”

The anesthesiologist, Dr. Devin Jack, said, “Give it another thirty seconds, and we should be good to go.” Almost without exception, the entire medical staff referred to him as just “Jack.”

I cringed. Dr. Torres wasn’t particularly known for his diplomacy, and I understood that in this situation brevity was key, but saying “I’m going to cut” within earshot of the patient seemed especially insensitive.

I watched the baby’s heart monitor dip even lower, and my anxiety went into overdrive. Fortunately, in the face of huge adrenaline surges, my tendency was to become laser focused. I shut out all the extraneous noise and began a mental run-through of what I anticipated I’d be up against.

A placental abruption meant the placenta tore away from the wall of the uterus before the baby was born. Its attachment to the uterine wall was essential in order for it to transfer oxygen from the mother into the umbilical cord and subsequently to the baby. If it tore away prematurely, the baby would be deprived of essential oxygen. If part of it tore away but some of it remained partially attached, the baby might get limited oxygen, but not in sufficient quantity to sustain life. As soon as an abruption occurred, you entered into a race for life.

I began to assemble all the equipment I anticipated needing so it would be within easy reach. I put the laryngoscope, a device that would allow me to look into the baby’s throat and see the vocal cords, on the side of the warming platform. Next to it, I placed what I guessed would be the appropriate-size endotracheal tube. I knew providing the baby with life-saving oxygen would be critical within the next few minutes, and the baby would have to be intubated immediately. I would extend the baby’s neck, put the laryngoscope into its mouth, visualize the vocal cords, then pass the endotracheal tube directly into its trachea. With some luck and a prayer, it would happen effortlessly. Was I feeling lucky?

As the frenzy began to reach a crescendo, I saw the big six-foot-wide door open, and a nurse escorted the woman’s husband into the room. “Mr. Carson, let me show you where you’re going to stand. You’re going to be right up here with your wife. We’re going to be able to proceed with the surgery using just the epidural for anesthesia. We didn’t need to put Becky to sleep. She’s awake and alert and will need your encouragement and comfort.” The nurse gave his hand a quick squeeze, mustered a smile of confidence, then guided him next to the side of the bed, where only his wife’s head emerged from under all the blue surgical drapes.

Mr. Carson had been hurriedly dressed in hospital scrubs identical to those worn by the operating room staff. The surgical cap had been hastily pulled over his head and came too far down his forehead. He repositioned it with a sweep of his hand, revealing more of his face. He was handsome, with strong features. Dark, curly hair stuck out from under the elastic band of the scrub cap. He had matching dark eyes, an olive complexion, and I could appreciate that the cotton scrub shirt covered a muscular torso. When he bent over to kiss his wife’s cheek, he disappeared behind the drape that had been hung to cordon off the surgical field.