A Trust Betrayed (21 page)

Authors: Mike Magner

Dingell was determined to block the deal. “This is clearly not in the public interest,” he said in his opening statement at the hearing. “The administration's proposal to exempt the Defense Department from important environmental laws will imperil drinking water supplies and eliminate vital state and federal authorities necessary to protect the public health and the environment. Nowhere has a single set of legislative proposals had so much audacity and so little merit. I would note that the Defense Department is supposed to defend the Nation, not to defile it.”

14

Dingell, an Army veteran of World War II with a strong environmental voting record, said regulations on pollution had never affected military readiness, “but the Defense Department like an old maid rushes around looking under the bed to find about what they may complain or what might threaten them. I could understand this from somebody else but I expect our Defense Department to be made of sterner stuff.” He noted that the Marine Corps had argued that virtually all of Camp Lejeune was an “operational range” that needed to be exempt from hazardous-waste laws, even though the base was filled with housing areas, recreation sites, and other areas that needed to be protected from toxic

contamination. Not to mention the fact that Camp Lejeune was already on the federal Superfund list requiring extensive and costly remediation.

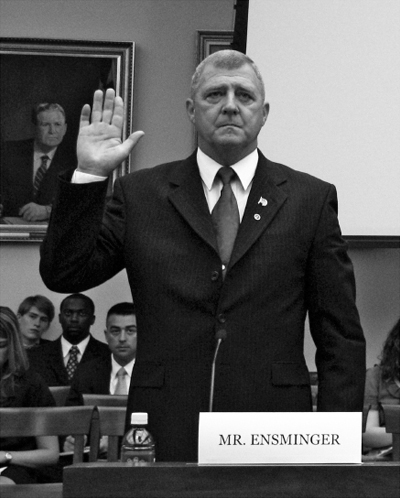

Later in the hearing, Dingell introduced his ace in the hole, Jerry Ensminger. “From my own past experiences it makes me shudder to think that the military would be granted immunities from any environmental regulations or the oversight by the federal and state agencies that were created for these purposes,” Ensminger said after describing Lejeune's history of pollution problems and the Navy's reluctance to address them. “To grant immunities we would be affording the Department of Defense a license to kill their own personnel and their families in a far more terrible way than any foreign enemy could ever kill them with bombs or bullets.”

Ensminger pointed out that 141 military installations around the country were on the Superfund list. “This alone should be testimony enough for the disregard that the Department of Defense has for the environment and the welfare of their own people,” he said. “However, if this fact is not enough of a deterrent, perhaps this next fact will convince you. My daughter, Jane, fought a courageous battle against her malignancy for nearly two and a half years. She literally went through hell and all of us that loved her went through hell with her. The leukemia eventually won that war. On 24 September 1985, Jane succumbed to her disease. She was only nine years old.”

One member of the committee who was deeply moved by Ensminger's testimony was Republican Richard Burr, soon to be elected as a senator from North Carolina. “I am curious if there is anybody in the audience from

DOD

or from the Corps who was assigned to come here and listen to Mr. Ensminger's testimony as it relates to what I think is a tragedy at Camp Lejeune?” Burr asked the packed crowd at the hearing. No one responded, and the congressman said

he was disgusted that military leaders responsible for the problems at Lejeune would not send a representative “to listen to the testimony from somebody who is willing to take their time, and probably pay their way, to come and sit through a very lengthy hearing and to wait to make one very, very important statement. Not just for you and not just for your daughter,” Burr told Ensminger, “but potentially for every man and woman who serves and every family who could potentially live on a base that is faced with this type of problem.”

After the hearing, most members of the committee came down to the witness table to shake Ensminger's hand, he recalled. Dingell's aide, Dick Frandsen, stood off to the side watching and waiting, “and when they were all done he came over and hugged me and said, âYou knocked it out of the park.'” The story of his daughter's death had a huge impact. Frandsen later told Ensminger that his testimony caused fourteen Republicans to change their minds and oppose the military exemptions. Two weeks after the hearing, Barton's spokesman said his committee would reserve the right to object if the exemptions were added to any bill authorizing programs for the Department of Defense.

Camp Lejeune was still a mess. More than twenty sewage spills occurred at the base between 1997 and 2004; two occurred within two days in May 2004, including one that sent 47,500 gallons of raw sewage into a creek feeding into the New River. Cleanup crews specializing in treating and removing toxic wastes were also at work around the installation performing studies, installing monitoring equipment, and beginning remediation on dozens of contaminated sites. Most of the projects were expected to take years to complete.

15

Into this environment waded the special panel appointed by the Marine Corps commandant to find out how the water contamination problems had been handled in the early 1980s. The committee called a public hearing for June 24, 2004, at the base

USO

center to allow interested parties to provide information. About fifty former residents of Lejeune showed up to testify, mostly in an angry, emotional manner.

“In the private sector this would be a felony . . . leaving people injured, sick and dying,” said Ellen Harris, who returned to the base where she had lived for five years from her current home in Fort Plain, Georgia. “We all looked like we had the mange.”

16

The chairman of the panel, Ron Packard, urged calm and order, saying each person who wanted to speak would have five minutes to do so. “We think that it would be inappropriate to play to the media,” he told the audience. “We have to carefully evaluate the Marine Corps' concerns and the concerns of the families.”

“As a victim who has suffered the ill effects of this contamination for over 30 years, I resent and am appalled at being allotted all of five minutes to provide you with my questions and concerns,” responded Paula Orellana of Chambersburg, Pennsylvania, who was born at Camp Lejeune and had lived there as a child in the 1970s. “This leads one to wonder: how many facts do you really want to find?”

Ensminger used his time to tell the four panel members that the group before them was just “a fraction of those affected by this travesty and tragedy.” He began telling his version of how the Marine Corps failed to protect the base water supply by placing supply wells dangerously close to heavily contaminated waste sites. Packard allowed Ensminger to continue for ten minutes and then tried to cut him off. The audience hollered for Ensminger to continue, so Packard relented. By the end of the hearing, the panel

was asking Ensminger for information. “I would ask you to screen your database and provide the names of all those we can interview,” said Richard Hearney, a retired Marine general.

Packard, the Marine Corps panel chairman, met later with a reporter for a Vietnam Veterans of America publication, Richard Currey, and tried to explain that the panel's assignment did not include examining health problems among former Lejeune residents. “We're listening very carefully to the concerns of the people who feel they or their families suffered as a result of the solvents in the water,” Packard said. “But it is not, however, the mandate of this panel to address those issues specifically or offer any form of redress. We're strictly a fact-finding group.”

17

Currey pointed out that “the inescapable heart of the matter” was the Marine Corps' failure to act for five years after learning that solvents were present in the base water supply. “The commandant has asked us to look very hard at that period of time, and determine if appropriate decisions were made in the context of the early 1980s,” Packard replied. “There wasn't as much known about toxins or their effects back then. This panel has to make a decision about how it looked to the Camp Lejeune leadership at that time.” It was not an easy task to piece together records of decisions made two decades earlier. “And in many cases we're dealing with people's memories,” Packard said. “That can get pretty hazy. We've had people who said they were not involved, but then we produced documents confirming they were. At which point they say they just don't recall the details.”

Packard insisted that his panel was operating under no constraints except for its specific mandate. “The commandant has not limited our range in terms of what we can look at or who we can talk to or consult with,” he said. “In fact, after we got under way, the Marine Corps has left us alone to do our work. But definitive conclusions about water contamination and human illness are simply not within this panel's purview.”

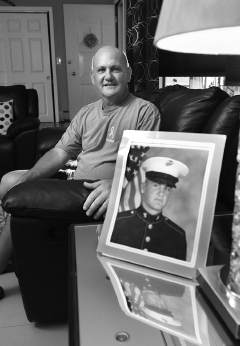

Jerry Ensminger testified numerous times before congressional committees about the contamination at Camp Lejeune.

Courtesy of Jerry Ensminger.

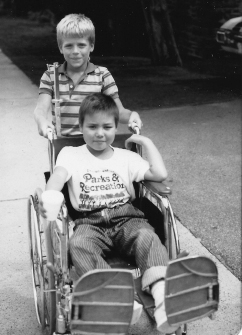

Nine-year-old Janey Ensminger (in wheelchair) and her cousin Matt Ensminger, not long before Janey's death from leukemia in 1985.

Courtesy of Eileen Ensminger.

Christopher Townsend was born at Camp Lejeune on March 16, 1967, and died less than four months later of multiple health problems.

Courtesy of Tom Townsend.