A Time to Stand (7 page)

Authors: Walter Lord

Although strong and durable, the church was set back so far that it still didn’t meet the south side of the compound. There remained a diagonal gap of about fifty yards in the southeast corner. This gap was the Alamo’s most glaring weakness, but there were other problems almost as big. Although the walls were wonderfully thick—usually two to three feet— they had no embrasures or barbettes. They were mostly twelve feet high, yet there were no parapets. An

acequia

or ditch provided water, but it could be blocked.

Worst of all, the place was so big. How could 80 men hope to do any good? Or even double that number? Colonel Neill had every right to feel depressed when the garrison assembled to discuss its situation the day after the Matamoros group left. And he had every right to feel surprised when the men passed the solemn resolution: “We consider it highly essential that the existing army remain at Bexar.”

With what? They had no food, no clothes, no money. To make any kind of stand, it would take a miracle—not just supplies, but new men, new leaders, even new spirit. And yet, these things do happen, and within a few weeks the Alamo

would undergo changes that Neill, a conscientious but unimaginative man, couldn’t hope to see. At the moment, however, there was nothing but a piece of paper expressing the belief of a few hungry, ill-clad men that San Antonio was a very important place to hold.

“The Supreme Government Is Supremely Indignant”

E

IGHT HUNDRED MILES SOUTH

of the Alamo, a well-knit, middle-aged Mexican buckled on his $7,000 sword, mounted a saddle heavy with gold-plated trim, and turned his horse north toward the Rio Grande. General Antonio López de Santa Anna also felt that San Antonio was an important place to hold; and he planned to do something about it.

To Santa Anna, the Texans’ seizure of the town was more than a strategic problem. It was a national outrage, a humiliating blow to his personal pride. It not only called for a remedy; it demanded revenge. “Don Santa Anna,” reported the Tamaulipas

Gazette,

“feeling as every true Mexican ought, the disgrace thus sustained by the Republic, is making every preparation to wipe out the stain in the blood of those perfidious foreigners.”

That was what hurt the most—”those perfidious foreigners.” It was bad enough being beaten, but to Santa Anna, being beaten by Americans was the greatest indignity of all. He recalled so well his first brush with them in 1813. Then he had come to Texas as a young lieutenant in the Royal Spanish Army to help throttle an early uprising against the Hapsburg

regime. At the Battle of Medina he saw the rebels crushed by a clever ambush—and some American hangers-on sent flying. Clearly, the undisciplined “Anglo” frontiersmen could never stand up to an army drilled in the European tradition.

Santa Anna had come a long way since Medina—mostly on the theory that if a man was nimble enough, he could end up on top. True, it didn’t always work; there was that time in 1813 when he was caught forging his commander’s name on a draft to cover some gambling debts. But he wriggled out of that, and since then it had certainly paid to be opportunistic. One March morning in 1821 the Spanish promoted him from captain to lieutenant colonel for beating some rebels; that afternoon he changed sides and got his full colonelcy. In 1822, now fighting for the Mexicans under Augustin Iturbi, he proved a dashing 28-year-old suitor for the hand of Iturbi’s 60-year-old sister … and soon became brigadier general. Later in the year, when Iturbi became Emperor Augustin I, Santa Anna solemnly swore, “I am and will be throughout life and till death your loyal Defender and Subject.” That December he launched a successful rebellion for a republic.

Sometimes on the winning side—sometimes not—Santa Anna was mixed up in one revolution after another over the next few years. Finally, he himself emerged on top in 1832: an apparently unwilling Cincinnatus whose liberal policies would end the chaos. “My whole ambition is restricted to beating my sword into a plowshare,” he wistfully announced from his country estate, where he liked to retire at dramatic moments. “I swear to you that I oppose all efforts aimed at destruction of the Constitution and that I would die before accepting any other power than that designated by it,” he scolded the clergy and the military men, who were against the liberal reforms he promised.

But all the time he was secretly dickering with these same conservative groups. And when finally convinced that he

would remain in the saddle, he dramatically shifted his ground in 1834. Sure at last of all the power in his own hands, Santa Anna scrapped his liberal program, jettisoned the Constitution of 1824 with its emphasis on states’ rights, and revamped the government along “centralist” lines … meaning a government run by himself direct from Mexico City.

It was at this point that Stephen Austin—languishing in the capital under arrest—despaired of ever getting freedom for Texas under Mexican rule. And he was right too; for Santa Anna quickly forgot that he only wanted to beat his sword into a plowshare. Soon he was dashing about the country, ruthlessly suppressing every attempt by the individual states to preserve their constitutional rights.

Prancing ahead of the troops with his escort of thirty dragoons, Santa Anna cut quite a figure. He was a master showman with a great sense of timing. He knew just when to brood at his hacienda until the people begged him to come forward; or plunge into danger till they begged him to hold back.

He was also a mountain of vanity. He affected a gold snuffbox. His epaulets and frogging dripped so heavily with silver that later they were easily made into a set of spoons. He collected Napoleonic bric-a-brac and felt there was an obvious comparison between the Emperor and himself. “He would listen to nothing which was not in accord with his ideas,” noted his top subordinate, General Vicente Filisola, who got to know him well.

Yet it would be so dangerous to underrate him. His boldness and energy revived a drooping army. His strength, his marvelous voice gave new hope to a nation weary of chaos. Even his appearance—he was much taller than the average Mexican—suggested an infinitely more promising leader than the shoddy collection of petty figures who had been wasting away the country’s resources. His shrewd sense of timing

made him not only a great politician, but often a skillful, imaginative general. And above all he was great at organization, and this more than anything was needed when Santa Anna once more emerged from “retirement” to develop the Texas campaign in the fall of 1835. At first he planned to invade next spring, but the capture of San Antonio changed everything. Now he would go at once.

The first problem was money. The Mexican Army was an appalling sieve. It had already consumed a back-breaking amount of money for a poor country worn out by civil war. And now more was needed. Undiscouraged, Santa Anna plunged into the task. He gave his personal security for a quick loan of 10,000 pesos. He hit the church for contributions—1,000 pesos from the Monterey Cathedral. He got rations on credit … but at double the usual price. He went to the loan sharks: Messrs. Rubio & Errazu supplied 400,000 pesos at an interest rate amounting to 48 per cent a year. Nor was that all. To make sure they got their money back, these gentlemen required the government to sign away the entire proceeds of a forced loan on four Mexican departments, plus various customs house duties, plus the right to bring in certain military supplies duty-free. Outrageous terms, Santa Anna agreed, but the money had to be raised.

Generals were much easier to find. Santa Anna’s growing assortment included Vicente Filisola, second-in-command and perhaps the stuffiest Italian in history … Adrian Woll, a tough French soldier of fortune … Juan José Andrade of the cavalry, with his delicate golden cigar tongs. They were every kind, sharing only their jealousy and suspicion of each other.

Graft and intrigue swirled around headquarters. Through the always obliging firm of Rubio & Errazu, General Castrillón secretly managed to lend the army some of his own money at 4 per cent a month. General Gaona cornered supplies along

the route and sold them back at 100 per cent profit. Colonel Ricardo Dromundo, master purveyor and another brother-in-law of Santa Anna, never even tried to account for the money given him for provisions.

Jockeying around headquarters, a good man to know was Ramón Caro, Santa Anna’s ferret-like secretary. If he seemed unfriendly, it might be wise to work through Colonel Juan Almonte, a bland chameleon who could be counted on to undermine Caro.

Beneath this glitter and intrigue were, as in every army, the unsung professionals. Fine officers like Lieutenant Colonel José de la Peña of the

Zapadores

battalion. Or General Urrea’s dull but conscientious paymaster Captain Alavez. (Everyone wondered how he rated such a beautiful wife.) But there were so few of these good men … and so many fops, dandies, favor-buyers, blackmailers. It all added up to one officer or non-com for every two privates in the Mexican Army.

No wonder the privates were so hard to catch. Bad leadership, poor pay and no glory were all that awaited them. Enlistments fell off, and local officials scraped the barrel to fill their quotas. The Yucatán battalion was loaded with helpless Mayan Indians—frightened, shivering men who couldn’t even understand the language. If a man deserted, there was no better punishment than to send him back. After Juan Basquez, an unfortunate shoemaker from Durango, ran away twice, he was sentenced to ten more years in the army without pay.

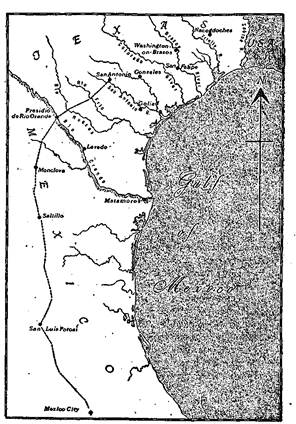

Willing and unwilling, the troops began assembling toward the end of December, 1835. First at San Luis Potosí, where Santa Anna laid much of the groundwork; then at Saltillo, where he planned to whip them all into shape. This was the real starting point for the great expedition—about 365 miles from San Antonio.

Santa Anna arrived at Saltillo on January 7, 1836 and

immediately collapsed with some sort of stomach-ache. For two weeks everything stopped while the Commander writhed in his bed. But if the experience did nothing else, it should have taught him that plans alone are not enough. The medical corps—so neat and impressive on paper—proved nonexistent. In his agony, the Commander-in-Chief finally hired a second-rate village practitioner named N. Reyes, who from that point went along as his personal physician.

Back at last on his feet, Santa Anna worked all the harder to get the men ready. An endless stream of orders poured on the hapless Ramón Caro, who sat at a portable

escritoire

frantically taking dictation: Tell Filisola to order 100,000 pounds of hardtack (“very, very necessary”) … have him buy 500 horses as replacement mounts (“fat, saddle-broken”). Minister of War Tornel was told to issue a proclamation that might give the men more spirit … to establish a Legion of Honor with a cross as insigne—“silver for the cavalrymen, but of gold for all officers.” General Cós, just back in disgrace from San Antonio, got special treatment. What did he mean by giving his word not to fight again? Forget it and join the march.

“His Excellency himself attends to all matters whether important or most trivial,” noted Captain Sanchez, Cós’ old adjutant, who dropped by headquarters hoping for a job. “I am astonished to see that he has personally assumed the authority of major general … of quartermaster, of commissary, of brigadier generals, of colonels, of captains, and even of corporals, purveyors,

arrieros

and

carreteros.”

Santa Anna thought of everything, in fact, except to teach the men how to shoot. Hating the recoil of their heavy, old-fashioned blunderbusses, the troops rarely fired from the shoulder. When they did, they never bothered to use the sights.

Otherwise nothing was omitted. Day after day the men drilled and deployed, marched and countermarched, until at

last Santa Anna was satisfied. On January 25 came the final Grand Review. As the glittering generalissimo watched from his horse, the men wheeled by in more or less good order—the senior officers in their dark blue uniforms with scarlet fronts … the dragoons with their shiny breastplates … the endless rows of infantry, scuffing along in their white cotton fatigue suits, already grimy with dust. On their heads they wore tall black shakos, complete with pompon and tiny visor. The total effect was oddly antique—like something out of Napoleon’s time.

But they were obviously soldiers; and if they looked a little Napoleonic, so much the better. Once again, how could the untrained American frontiersmen stand up to troops like these? As Minister of War Tornel put it, “The superiority of the Mexican soldier over the mountaineers of Kentucky and the hunters of Missouri is well known. Veterans seasoned by twenty years of wars can’t be intimidated by the presence of an army ignorant of the art of war, incapable of discipline, and renowned for insubordination.”

The comparison omitted an important element. The rifles of the Kentucky mountaineers were accurate at two hundred yards; while the Mexican

escopetas—

although authentic English surplus from the days of Waterloo—could barely reach seventy yards. Tornel would not have cared; tactics would win in the end; the Americans were pathetically “ignorant of manoeuvres on a large scale.”

Hope soaring, the troops began moving out of Saltillo the day after the Grand Review. First, General Urrea’s infantry … branching off to the east, heading for the Gulf Coast to serve as the army’s right wing. This brigade would be pretty much of a side show for a while.