A Thousand Laurie Lees (16 page)

Read A Thousand Laurie Lees Online

Authors: Adam Horovitz

Fortunately, Laurie was in a mood to defend the valley ferociously, despite illness and near blindness. A series of meetings were set up, at which Laurie sat in, totemic, his hands on his stick in a quietly combative pose, making statements like: ‘[The Slad Valley is] the green lung of Stroud. If we permit this to go ahead without resistance, it will be a self-inflicted wound that not even time will heal. The word ‘development’ is just a euphemism for ravagement and exploitation … The valley, with its landscape of tangled woods and sprawling fields, should be left to rabbits, badgers and old codgers like me.’

1

It wasn’t just old codgers that took up the defence of the valley from exploitation, or wanted to be a part of it, though. Poets and artists, walkers and drinkers, locals and tourists all cried for Slad to be spared – the valley turned out to be everyone’s valley and I, as vocal in its defence in and around Stroud as I could manage, discovered and rediscovered a huge number of people who would gladly call it their own.

Carolyn White, who had spent winters in Driftcombe painting the sprawling fields and tangled woodlands in all their stark glory when I was a teenager, had put down her flag in the landscape with brutal expertise. She became more and more widely noticed for her broad impressionist take on Slad, fixing it further in the mind’s eye as somewhere of special note. She returned often to the valley, always finding something new to paint, some new way to look at light. When I encountered her in Stroud talk would routinely return to that landscape, the feel of it, the people in it and sometimes the parties she’d held in Driftcombe that I had come to. She remembered me running from one of these when Rich, a year or two younger than me and the son of one of her friends, proposed holding a séance in the most haunted parts of the house. The spirit apparently in attendance was female and her name began with an F. Having lost my mother, Frances, only a couple of years before, I jumped from the board and ran, taking my father’s midsummer jogging route in reverse, and at full pelt, all the way home.

Carolyn’s canvases became more and more like stained glass; she caught the valley at its richest and coldest, always making it sing with light. She was a short and intense woman, her rounded, good-natured face hiding fierce eyes and a sharp opinion of poets (‘It’s all very well to write poetry, Adam; just don’t become one of those types who won’t help a person push a stuck car up a hill because “it’s not the sort of thing a poet does!”’). She could often be found wandering the valley carrying easel and paint, chasing the sun.

The only time she encountered Oliver Heywood, equally a master of capturing the valley in light, was near Rose Cottage in Elcombe. They were coming through the woods in opposite directions, carrying recognisably similar equipment; both had spent years combing the valley for places to stop and paint and yet they only met that once, pausing to make small talk and recognise each other as artists before moving on, interested more in the valley itself than in one another, and never, apparently, to meet again.

There, still defending the valley in her own quiet way, was Diana Lodge, capturing details of the valley where Carolyn and Oliver’s work looked at broader landscapes. In her late eighties she was still producing many dozens of paintings a year and selling them at the Stroud Subscription Rooms for charity, but she had weathered ever further into the landscape, driving erratically between Slad, Stroud and Prinknash Abbey.

But it was Laurie’s voice that mattered most in the battle to protect and protest. Laurie, in cahoots with Val Hennessey, concocted a defence of Slad against development for the

Daily Mail

, a story which reached out across Britain and the world, particularly to Japan and America. A tidal wave of protest came rushing back, from people who loved

Cider with Rosie

, who loved the valley or their imagined version of it, giving the landscape a loud and unanimous voice against the steady spread of tarmac and flood risk, the twin erosions of soil and hope.

The next year, Laurie died. Although Slad was safe for a while and free to allow the creep of small creatures, old codgers and unfettered leaf-light through its scattered fields and woods, the rush of hope returned to a trickle and my dreams of houses walking in on chicken legs and colonising the valley returned. I saw them strutting and scratching through Slad as if they had wandered out of some Russian fairytale, before settling on all the beloved places I had known.

At the time I was writing poetry for performance, invective in verse; nightmares and poems naturally spilled over into one another. In one: ‘They bought the woods above Slad/and are erecting a wicker Laurie Lee/to burn houses in: hot living for the millennium.’ In another, the nightmares went beyond millennial frenzy and imagined a dystopian Slad:

A

T

T

HIS

T

IME

Statistics; not available.

Plans and applications; not available.

Photocopied reports from bloody depths of bureaucracy; not available.

Orchards; not available.

Aspirin; not available.

Pleasant valley walks; not available.

Childhood available elsewhere.

Sunday school; not available.

Imagination; not available.

Cider presses; not available.

Big dogs with grotty noses; not available.

Kissing gates; not available.

Beer; not available.

Reporters only available if beer available.

Books; not available.

Economists; not available.

Bare-footed taxmen no longer available.

Miffed of Miserden; not available.

Sculptors; not available.

Cowslips; not available.

Pools to drown in; not available.

Sewage and concrete available always

if price is right.

Prices; not available.

Wallets; not available.

Poets and anarchists not available

except for lecture tours in far countries

with big wars.

England wicket keepers; not available.

Trees; not available.

Sunsets; not available.

Badgers not available unless peanuts paid for.

Bungalows available at all times.

Pig-farmers; not available.

Sheep; not available.

Locals not available for comment or otherwise.

Telephones available, but not as available as vandals.

Chaffinches; not available.

Torches not available or necessary.

Bicycles; not available.

BBC film crews and other archaeologists; available.

Holographic Laurie Lee; available.

Midsummer morning traffic-log; available.

Small chunks of Cotswold stone; available.

Mortgages; available.

Rustic 1930’s charm available

from staff of three-story theme restaurant

on request.

Chartered helicopter flights; available.

Genuine gravestones; available.

‘Cider with Disney’; available.

Sex in aforementioned bungalows; available.

Prices available for that.

Prime Minister available for facile speeches

about importance of countryside

and visits from Presidents

Jilly Cooper; available.

Jilly Cooper; available.

Explosives not available.

At

this

time.

Note

1

Grove, Valerie,

Laurie Lee: The Well-Loved Stranger

, p. 500.

15

D

eath is an implosion; a sucking away of memory, a shrivelling of fact until it is indivisible from myth. In the summer of 1995, Marcelle Papworth, the wife of John, died. The Papworths had long ago left the valley, but they owned some of the woodland behind the house, and John wanted Marcelle to be buried there. Approval was sought, and was only granted after strenuous debate, according to the nature of bureaucracy in small areas of outstanding natural beauty.

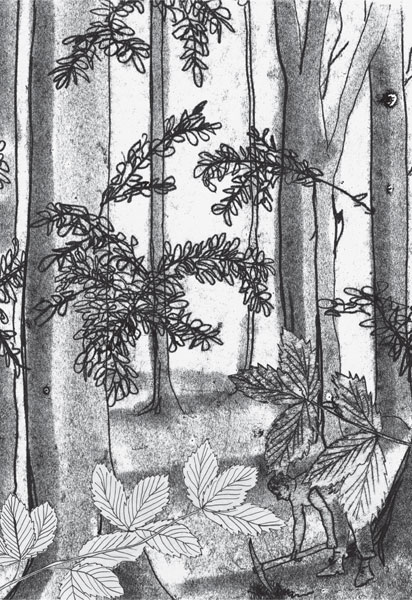

The location of the grave site was far off the beaten track, on a little hillock that catches the sun through the trees late but not too late on a summer’s day, in amongst the ruins of a more crowded century. Earth had silted up over fading walls, moss-encrusted semi-structures so embraced by root and soil that it is hard now to tell if they were once houses or merely garden or animal enclosures. The only way to reach it is to walk, or park precariously on the steep and slithering S bend – the lane barely allows for cars to pass and the green lanes through Catswood are only good for hiding motorbikes or riding horses.

Granted the right for a woodland burial, and the ground consecrated, the Papworths then found themselves without a digging crew. First, the pub was tried. Eventually phone calls were made to Diana Lodge, many of whose grandchildren were in the valley at the time, and she sent Brodie, Caitlin and Owen along to help dig. It was hard, rocky ground and a hot summer; more hands were needed. I was called in, along with Euan, to help make the work go faster.

Every step down through the hill was layered with stone and mud, bonded together into a kind of gristle, tough and impenetrable. The Lodges had got a couple of feet in before Euan and I arrived. They were desperately in need of a rest. We took it in turns with a pickaxe and shovel, smashing through layers of the past, throwing out small animal skulls we’d crushed, yanking at roots, our fingernails filthy, gloves forgotten, blisters rising on our hands, watching worms writhe back the way they had come after finding their usual routes exposed. The task began to seem impossible, so the work party turned to laughter and beer as it dug, determined not to let this armoured skin of stone defeat us. Old stories of childhood, jokes and songs, tender insults and harsh encouragement flew back and forth across the deepening grave; anything to distract us from the impossibility and the enormity of the task, the responsibility of it.

As the day wore on and we wore out, new fervour came over Euan (ever the man to stare defeat in the face, snarl ‘

Yew

’ve

GOT

to be

KIDDING

me!’ and plough on regardless, whether it was playing golf on the Sega Megadrive until six in the morning or digging an impossible grave). He pummelled away at the hole, getting deeper and deeper into the ground as the sun sank into the opposite hill, trailing a coat of honey down the fields. Sometimes he wouldn’t even let others take over and carried on hammering, a fierce look in his eyes, only stopping to let people in so that they could clear the debris he had created.

Between us we made it before sunset, got as close to six feet deep as we could, with more than enough stone dug up to discourage any animal from digging down through it when it was replaced. We went to the Woolpack to celebrate.

‘What’ve you been doing?’ we were asked.

‘Digging a grave in Elcombe,’ we replied. There was much muttering in the pub.

The funeral itself is a hazy memory, blocked out by mists of hangover and the previous day’s hard work. We diggers were there, all salt, cynicism and mordant laughter from the strain of the dig long left behind. John, caught between liturgical ecstasy and grief, stood at the head of the grave like a woodland god in priest’s robes, filling the wood with his voice and with the memory of Marcelle.

![]()

Three years later, I was in the Woolpack having a drink with Everest. Janette, living with him in the village at that time, and working in the pub kitchen, finished her shift and came to join us.

‘Have you heard about the grave in the woods above Elcombe?’ she asked me.

‘Mmm,’ I replied, sipping my pint.

‘Martin was telling me about it,’ she continued, a glimmer of disapproving excitement in her eyes. ‘It was years ago. Apparently this man came in and wanted help digging a grave for his wife. Nobody would do it! They all said it was too stony. But there’s a grave there now. Isn’t that weird?’

‘How long ago was this?’ I asked.

‘Maybe thirty years ago,’ said Janette. ‘It’s weird. Why would someone do that?’

‘I helped dig that grave,’ I said. ‘A couple of years ago.’

‘I don’t believe you,’ said Janette.