A Step Farther Out (36 page)

Dr. Gale then reviewed starship systems, none going faster than light, and not surprisingly concluded that they are quite feasible if a bit expensive. Again, so far, not a lot new; but he also pointed out that given the limits of a solar system, the impulse to build starships must be reasonably high. We could go make use of other stars.

There's only one problem with that—someone else may want the materials. In fact, if you play exponential growth games, it will be only a few thousand years before humanity will have spread far throughout the Galaxy, and may well be tearing stars apart and moving big things around. (See "That Buck Rogers Stuff" for more details.) And if

we

are pretty near that stage, why haven't others done it? Those are effects we would probably see.

Thus, perhaps we are alone in this galaxy—and according to Dr. Gale, that may be as well, because in far fewer than a million years we will want it

all

for ourselves. Meanwhile it's a race—and he does not discount the possibility of a race to another galaxy so that we can lay claim before someone else does. And do note: if you project human progress and use that as a model, it is strange that the outsiders are not here yet. (Devotees of the UFO persuasion have their own ideas on that.)

In fact, Gale notes, there is no reason why within a few tens of thousands of years humanity will not be interfering with the evolution of the universe: preventing lovely and useful matter and energy from collapsing into Black Holes where we can't get at it; making stars grow in the direction we want and need; etc. There is, Gale concludes, no limit to growth except to meet someone else as powerful as we who needs the growth materials we must have. On that note he ended.

But—of course there is a limit. The universe itself is not eternal. It can't last forever.

It can't—but perhaps we can, says Freeman Dyson.

* * *

No one could ever accuse Freeman Dyson of thinking small. His "Dyson Spheres" or "Dyson Shells," large systems for trapping the energy of the sun so that not so much is wasted, were the inspiration for Larry Niven's RINGWORLD and Shaw's ORBITSVILLE and a number of other stories. Although I didn't get the concept from him, Dyson was the first non-SF type I know of who examined the space industrialization possibilities implied by the laser-launching system I've employed in many stories. He is a modern renaissance man who thinks both broadly and deeply.

He began simply enough, by quoting from Stephen Weinberg's THE FIRST THREE MINUTES. Like many modern cosmologists, Weinberg finds that the universe is doomed, and that disturbs him. He says, "The more the universe seems comprehensible, the more it seems pointless."

Of course nearly all religions have taught that "the world" (which certainly implies "universe") will inevitably come to an end. The Last Trump will sound either from Heimdall's horn or Gabriel's. Then too, true atheist humanism has never had any answer to the feeling that it is all pointless; of course it is. (This is, incidentally, discussed brilliantly and at length in Henri de Lubac, SJ., THE DRAMA OF ATHEIST HUMANISM, Meridian 1963.) It is only a true modern who can proclaim that the universe has no purpose (in the sense that it is no more than a dance of the atoms) and at "the same time bewail its pointless impermanence.

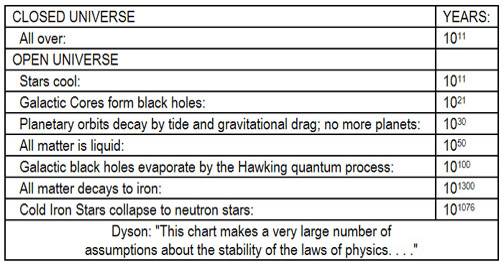

Dyson, however, did not address the theology of the universe; he stayed strictly within its physics, looking at the probable futures. The first result of this is given in Figure 31.

Now note that last number: 10

10

. To the best of my recollection—and that of all the others in attendance at the panel—no one has

ever

tried to project the future

that

far before; but then, one learns to expect great things from Freeman Dyson.

He was not finished, though. Granted that 10

1076

is a large number, still, it is finite; the universe does eventually come to an end. However—do we have to?

Now that sounds like a silly question. How can we survive the end of the universe?

First

a question: is the basis of consciousness matter or structure? That is equivalent to asking whether sentient black clouds or sentient computers are possible: can we, in other words, make a one-for-one transformation of a conscious being, replacing part for part, and still have a conscious entity? And will it be the same entity?

Note that this is also equivalent to asking whether you could send a conscious being by wire—tear down the original and transmit a message that would cause an exact reconstruction at the other end.

___________

THE UNIVERSE ACCORDING

TO FREEMAN DYSON

___________

___________

If this is possible, then the second question: are biological entities subject to scaling? One presumes that if the basis of consciousness is structure, not the physical matter, then indeed we are subject to scaling: that we could build a one-for-one transform of ourselves, into computers, or into biological processes, that could be so scaled that the subjective lifetime is infinite.

Dyson then proceeded to demonstrate this with what I call the "Integrals of Immortality." I haven't room to reproduce them here, and I suspect that even freshman calculus would turn off my readers, but indeed they exist, and given the assumptions Dyson has indeed "proved" the possibility of an infinite conscious lifetime—which is to say that for all time a properly constructed entity could accumulate new experiences and fresh information, running out of neither experiences nor time in which to enjoy them.

Couple that with the Goedel theorem of mathematics which states that there is no limit to growth: there will always be new questions which cannot be answered without new assumptions, which will themselves generate new questions which cannot be answered in

that

system: and you have something to think about.

Quite an exciting panel. As I said when it was over, I had gone to the panel expecting something interesting, but after all, these people were more or less amateurs at my business (far out speculation about the future); I certainly wasn't prepared for immortality and 10

1076

years!

Carl Sagan's discussion was on aliens: any moderate extrapolation of human capabilities shows that within a thousand years we are likely to be visiting other stars—either physically, or certainly with messages. Thus Fermi's question: Where Are The Others? They should have been here by now.

Sagan examined several possibilities.

First, perhaps we are very early. This Sagan rejects—our sun is not very old compared to the age of the galaxy, and almost certainly there have been others. (Assuming that there are ever going to

be

others. Continuing along that line takes us to theology, and is outside the scope of this chapter; for our purposes we assume that life can come about given the right physical conditions, and that having come about it evolves. This is not, so far as I know, at all inconsistent with religion, or at least with the Catholic religion.)

Secondly, then, perhaps high-level civilizations simply cannot exist: when they reach a certain level of capability they destroy themselves. We can certainly come up with scenarios in which that happens to

us,

and it's something to think about.

Third, perhaps advances in biology bring about immortality, and that in turn changes motivations, specifically, that immortality removes the imperative for colonization and expansion. I find this unlikely; I would think that immortals would still have an imperative for exploration at the very least; I find Larry Niven's ancient Louis Wu quite believable.

Fourth, there is the "zoo" hypothesis: we are either on exhibition, or somehow subject to non-interference regulations. Obviously this is not a new idea for science fiction readers; what's interesting is that it could be presented to a bunch of scientists without getting a laugh.

Finally, Sagan speculates, perhaps there are technologies so much beyond ours that we simply cannot imagine them: the effects of really advanced technologies are not recognized by us. If so, we have an interesting future in store—because no question about it, we are already approaching the point at which we could make others unambiguously aware of our existence.

Sagan was followed by a chap from the State Department, who said among other things that we are now learning to look far into the future, and this is "particularly due to the work of people like Carl Sagan." Now I have nothing but admiration for Sagan, and I shouldn't like to take anything from his reputation; but I think he would be among the first to say that much of his speculation is a bit old hat to science fiction writers and fans; and my feeling as I listened to the State Department chap was 'They're doing it to us again!" In fact, after listening to the scientists congratulate themselves over having, finally, allowed at one of their meetings some elementary speculations of the kind that have gone on in SF convention panels for decades, I very nearly titled this column "Out in the Cold Again"; however that would be uncharitable, and I am truly grateful for the opportunity to have heard Dyson.

It isn't as if it were unknown for SF people to steal from the scientists; now we get a dose of our own medicine.

It doesn't taste very good, but what the hell.

* * *

As usual I'm running out of space before I can cover even half of what went on at the meeting; but I can't end without mentioning the dinosaurs.

Warm-blooded dinosaurs. I didn't get to the panel, but I did attend the press conference. There's something mind-boggling about the whole thing: how to understand, from a few scraps of bone and fossil, the physiology of critters that died away 60 million years ago.

They were, after all, rather successful: dinosaurs, ranging in size from about that of a modern wild turkey to beasts massing 80 tons live weight, dominated the planet for nearly 100 million years. Most of them were

big.

According to the panel chaired by Dr. Everett Olson of UCLA, more than 50% of the dinosaurs were larger than all but 2% of the mammals; 70 to 80% of the mammals alive today are smaller than the smallest dinosaur.

As Olson said this, something occurred to me: if they were so large, their major problem would be getting

rid

of heat. They are on the wrong side of the surface-to-volume relationship, just as an overweight person finds it very difficult to lose a few pounds. (There ain't no justice: it's easy for a thin person to reduce.) I mentioned that in the question period and found that this seems to be a relatively new idea—not that I thought of it first, but that the biologists concerned with the dinosaurs have only in the last couple of years looked at the beasties from that point of view.

However—Walt Disney did present the "overheat" model of dinosaur extinction in

Fantasia,

as Olson pointed out to me; and looking at the long-term climate models, there's at least a chance that this is what happened to them. They cooked in their own juices.

It's all complicated because we are not even sure where the continents were when the dinosaurs flourished: it has been that long, and they were around a very long time. If you rearrange the land masses to the best guesses of the configuration of 100 million years ago, nearly all the dinosaurs lived within 40 to 50 degrees of the equator—except that there is reported a fossil print from Spitzbergen and no one is sure that Spitzbergen was that far south even back then.

There was no real conclusion, and my apologies for taking your time with the question. It interests me, even if the best I can say about warm-blooded dinosaurs is that "nobody thinks they all were 'warm-blooded' but many respectable paleobiologists think

some

were; a few think none were." As to what killed them all off, there aren't any fewer theories now than there were a few years ago.

And at least some theorists say that the warm-blooded dinosaurs became birds, and the cold-blooded ones died or became reptiles, and what's all the problem?

* * *

The final controversy was over sociobiology, and that's important enough to warrant a full column one day. At the AAAS meeting the usual group calling itself the "Committee Against Racism" showed up to enforce its idea of scientific integrity by preventing Dr. Wilson from speaking: their brilliant idea was to shout "Wilson, you're all wet!" and pour water on him, obviously refuting his ideas. Sigh.

But for all that, it was a quiet meeting, not like the one a few years ago when the "concerned" whatever they were hit Senator—then Vice President—Hubert Humphrey right smack in the mush with a ripe tomato, or the one in San Francisco at which the Racism Committee tried to quiet Sydney Hook.

I usually like to summarize the year in science, but this year it is hard. The mood was one of optimism for the technological and scientific advances of the year, and profound gloom because of the prevailing attitude of government.

We

can

do a lot. Every year the discoveries come forth, and the promise of the future gets brighter; but for the moment at least there's the question of whether we will

do

anything about bringing forth that promise.