A Step Farther Out (12 page)

There are numerous stories of ghost cities in the Mediterranean. One can often be seen across the straits of Messina: a full city, with moving traffic, nestled onto the dry and barren hills. The illusion has been known for at least three thousand years.

What happens is that changing air densities will affect light rays so that under the proper conditions the image is refracted over the horizon. A British regiment marching in Aden is seen a hundred miles away. Ghostly images of cities form on barren shorelines.

This is rare on Earth. On Venus it's inevitable. The Venerian atmosphere is so thick that light is refracted through 90° and more. The whole planet is visible from any point on the surface. The explorer will seem to stand in the bottom of an enormous bowl, with cliffs towering high above him.

This doesn't have a lot to do with the subject of this column, but it fascinates me. Venus must be a confusing place, where one sees the back of one's own head spread about on the top of an enormous cliff. . .

* * *

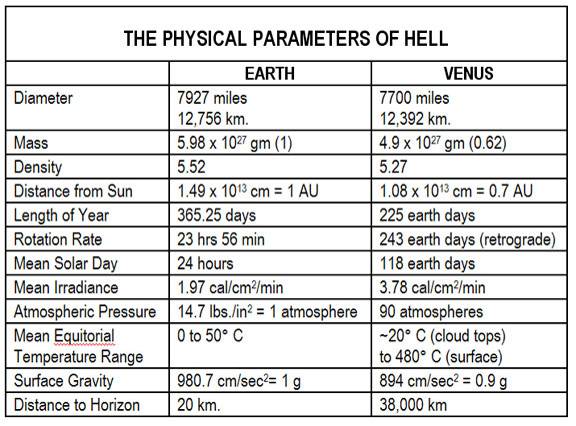

The mirages might be worth seeing, but there's not a lot else to attract colonists or tourists. Carl Sagan, Cornell U's resident genius and expert on Venus, once said "Venus is very much like Hell," and a glance at Figure 10 shows why.

It's just not a very attractive place to live. In fact, a more useless planet is hard to imagine. What good is a lump of desert whose surface temperature is up there about the melting point of lead, whose atmosphere is too thick, with winds of fearful velocity and force blowing dust across craters and jumbled structures like the surface of the Moon?

Some writers have proposed that since we can never visit Venus (and wouldn't want to if we could), we should make her the Solar System's garbage heap. Venus could become the repository for all the long-term radioactive wastes produced by nuclear power plants. It's cheaper to drop a load onto the surface of Venus than to send it into the Sun, and what other use do we have for Hell anyway?

Quite a lot: Venus is very likely to become the first terraformed planet. In a few hundred years there may be more people living on Venus than live on Earth at present.

The asteroids can be one frontier for the future, as I have described elsewhere; but they'll never be developed into a New World. That's reserved for Venus.

Not only can we terraform Venus, but we could probably get the job done in this century, using present-day technology. The whole cost is unlikely to be greater than a medium-sized war, and the pay-off is enormous: a whole New World, a frontier to absorb adventurers and the discontented. Few wars of conquest ever yielded a fraction of that.

Hardened veteran SF readers will have recognized the title of this chapter as coming from a 1955 ASTOUNDING novelette by Poul Anderson. His 'The Big Rain" should rank with all the other successful predictions by SF writers: when the Big Rain comes, we can live on Venus.

The Venerian atmosphere consists mainly of carbon dioxide plus some other junk that we'd like to get rid of.

__________

__________

__________

The junk is water soluble, and will wash away when we get the rain to fall.

That thick CO

2

blanket is the cause of all Venus's problems. Solar radiation comes in, a lot of it as visible light and hotter, into the ultra-violet. It penetrates into the atmosphere and is absorbed. As Venus slowly rotates, until she faces the absolute black of outer space, the absorbed radiation tries to go back out. But it has cooled off somewhat, from ultra-violet to infra-red. IR is absorbed nicely by carbon dioxide. The heat never gets back out, and up goes the Venetian temperature. This is called "the greenhouse effect" and works quite nicely for farmers on Earth, as well as out there.

In fact, there are theorists who wonder if burning all those fossil fuels won't loose so much CO

2

into our own atmosphere in a couple of generations as to bring Earth's temperature up sharply. The result would be melting ice at the poles, and the drowning of most of our sea-coast cities.

Before we get too alarmed at that, though, there's something else to worry about: it seems that far from rising, the average temperature of the Earth

is falling,

and we may be due for a new ice age, complete with glaciers in North America and like that, within the next hundred years. For more on both subjects see other chapters; just now we're concerned with reducing the Venerian fever to manageable levels.

We need to break up that thick CO

2

layer around Venus. This will automatically liberate oxygen. It will also chop down the atmospheric pressure to something tolerable.

Breaking up CO

2

is a rather simple task Plants do it all the time. We'll need a pretty rugged plant, since the atmospheric temperatures of Venus range from below freezing to live steam, but fortunately one of the most efficient CO

2

converters is also one of the most rugged.

In fact, it's generally thought that the blue-green algae were responsible for Earth's keeping her cool and not getting covered with a thick CO

2

blanket like her sister.

The algae will need sunlight, water, and CO

2

. There's no question about finding those on Venus. The temperatures are all right, too, at least in the upper atmosphere where we'll seed the algae.

This isn't just theory. "Venus jar" tests have shown that blue-green algae thrive in the best reproduction of the upper Venerian atmosphere we can make, breaking down the CO

2

and giving off oxygen at ever-increasing rates. In fact, to these algae, Venerian conditions are not Hell but Heaven.

We have the algae, and we can build rockets to send them. About a hundred rockets should do the job. Say each rocket costs 100 million dollars, and the ten billion dollar price doesn't seem unreasonable. Say we're off by a factor of ten, and we've a hundred billion, less than wars cost; and out of

that

much money we should be able to get a couple of manned Venus-orbit laboratories as a bonus. It will be, after all, a once-in-evolutionary-lifetimes opportunity.

Once the algae are sprayed into the upper atmosphere, they happily eat up CO

2

and give off oxygen. They have no competition. Nothing eats them, and there's plenty of room for expansion, plenty to eat, and lots of sunlight.

Some calculations show that within a year of the initial infection the surface of Venus will be visible to Earth telescopes. Meanwhile the algae go on doing their thing. The atmosphere clears. Sunlight coming in begins to radiate back out. The atmospheric temperature falls, and lower levels are invaded by the algae.

There is about 100 inches of precipitable water in the Venerian atmosphere. This means that if it all fell as rain, it would cover the entire surface to a depth of 100 inches.

This sounds like a lot until you contemplate the miles of water standing over most of the Earth. Still, 100 inches is respectable. Compare it to Mars, with 10

microns

of precipitable water, and you'll see what I mean.

As the air above Venus cools, raindrops form. Eventually it will rain, and rain, and rain. The first planet-wide storm probably won't ever get to the surface: the rain will evaporate long before that But as it evaporates, it cools still another layer of atmosphere; down move the algae.

Repeat as needed. In no more than twenty years

from

Go, the Big Rain will strike the ground. Craters will become lakes. Depressions will become shallow seas. Rivers will begin carving channels.

As Venus slowly turns, there may be snow on the night side. A water-table will develop. Deserts that may be a billion years old will turn to mud.

By now the surface will be tolerable to humans with protective equipment, and the seeding can begin. Scientists will want to move very carefully, introducing only the

right

plants and insects, fearful lest an unbalanced ecology result. Against this there will be pressure from colonists who want the job over and done with.

Some will demand that we dump a little of everything we can think of onto Venus and let competition lake its course; an ecology will result inevitably, although we may not be able to predict what it will be.

There will also be tailored organisms. Microbiologists are already to the stage of switching genes from one species to another, and it shouldn't be long before this is done with higher plants and animals.

After all, Venus will have special conditions. That long rotation period means severe winters, like the Arctic tundra or worse. Much of Venus may resemble Siberia or the North Slopes of Alaska, which, if you haven't seen them, are second only to Antarctica as candidates for the most desolate spots on Earth. On the other hand, Venus will still have a thick atmosphere, and she's closer to the Sun. We don't know what the final temperature will be, or how much heat-pumping the atmosphere can do.

It may not be the most pleasant world imaginable. Some writers have speculated that Venetian colonists will be nomads, staying on the move to live in perpetual sunshine. Others have described a world of paired cities connected by rails: as sunset approaches, the inhabitants escape the winter night by travel to their city's twin at the antipodes, somewhat as the Martian colonists migrated yearly in RED PLANET.

Much of this scheme was described by Carl Sagan in a 1961 article in

Science.

Poul Anderson amplified it in

"

To Build A World,"

Galaxy,

1964 (June). In Poul's story there was fierce competition for the better parts of Venus, resulting in a clan structure social system and innumerable limited wars between clans. It's a reasonable projection: the first settlements will be small, probably dominated by one man, and intermarriage may well result in clans.

We haven't yet mapped the face of Venus, so we don't know where or how large the seas will be. We don't know a lot (really, almost nothing) about the sub-structure of Venerian soil. How much water will be absorbed? At what level will a water-table form?

For that matter, will it be enough to introduce our algae to get everything started, or will we also have to provide fertilizers: phosphorus, trace elements, that sort of thing?

Our massive tampering with atmospheric energies and surface temperatures may trigger tectonic activities. Venus may erupt in a number of places, and spew out even more CO

2

, water vapor, methane, and such like.

Project Morning Star won't be all smooth sailing. There will undoubtedly be unforeseen problems. For all that, the terraforming of Venus is no pipe dream. We could do it. We can do it right now, if we want to pay for it. We can create a new frontier, larger than ever was the New World.

In other words, there's room here for more stories than we had about the "old" Venus with her swamps and dinosaurs. True, we won't have any intelligent Venerians to contend with. It's unlikely that there's any life on Venus at all.

Unlikely but not impossible. There are, after all, Earth-like conditions of temperature and pressure in the Venerian atmosphere, and this is about the only planet—other than Earth—in the Solar System that can make that statement. Moreover, it may be that there have

always

been spots with Terrestrial conditions on Venus.

True, life isn't likely to have evolved under present Venerian conditions, but some planetary scientists now believe that Venus was once much more like Earth. Then, for reasons not completely understood, the planet began to heat up and dry out.

If by that time life had evolved, it may have taken to the air, and be hanging around there yet.

It isn't likely, of course. If Venus had really active bugs they should be busily tearing off the CO

2

cover that keeps Venus hot, and we wouldn't need to infect the Queen of Heaven with blue-green algae.

If there are any native Venerian bugs, Project Morning Star will probably doom them to extinction.

* * *

We have the technology to make Venus a place where we can live. Have we the right to do it?

Should we,

granted that we can?

After all, this is "pollution" on a grand scale. True it's not pollution to our way of thinking; but what's good clean air to us is certainly un-natural to Venus.

I suppose that we can and probably will debate this question for a long time to come, and when the debate is finished I suspect that no one will have changed opinion by one jot. Those who feel it monstrous to go about interfering with "nature," and see the terraforming of Venus as blasphemy (they will probably use the term "obscene") are not likely to change their minds.

Those who see Project Morning Star as the most glorious opportunity that has yet faced man are unlikely to be concerned about Venerian gas-bags or other hypothetical Venerian critters (beyond building them a zoo to live in).

Meanwhile, one thing is certain: it is possible that within my lifetime I could dateline this column "Venusberg." We can do it, and some of you could live there. Just after the Big Rain.

* * *

In the years since the above was written we have gained considerably more knowledge of Venus. Conditions there are even more frightful than we thought, and the terraforming of Venus appears now- to be more difficult than I knew.