A Step Away from Paradise: A Tibetan Lama's Extraordinary Journey to a Land of Immortality (5 page)

Authors: Thomas Shor

Tulshuk Lingpa had the

purba

tucked under his belt beneath his robes. He handed it respectfully to the lama, who examined it closely and told him to keep it safely for it would bring him much power.

The

purba

, taken from a photo of Tulshuk Lingpa in the 1950s

Dorje Dechen Lingpa handed the

purba

back to the boy and spoke confidentially to him. ‘I will be leaving soon,’ the older lama said. ‘I am going to Sikkim to try to open the way to Beyul Demoshong, the Hidden Valley where none has been. Thirty are coming with me. But the way is difficult—we must cross the plains of Tibet, braving highwaymen, cross the Himalayan passes south into Sikkim and then climb the slopes of the Mountain of the Five Heavenly Treasures, Mount Kanchenjunga. If I am successful I will never return and we may never see each other again. I want you to know something: There is a remarkable future laid out for you. You won’t stay here but travel to distant lands. People from far away will know your name. If I fail to open the way, then you will be the one.’

Just before Dorje Dechen Lingpa set out on what proved to be his final journey (his attempt to open the way was unsuccessful and he was to die before returning to Golok), he presided over the coronation of the young boy at the Domang Gompa. He declared the boy a

lingpa

and bestowed upon him the name Tulshuk Lingpa.

Tulshuk means crazy.

I used to go almost every afternoon to Kunsang’s flat in Darjeeling to speak with him about his father. This was during a rainy monsoon. Kunsang lives with his family in the market above a restaurant, a low, one room watering hole which was usually empty but for a few men drinking millet beer huddled around a table in the middle of which stood a single candle. Upstairs, the narrow hall that led to the doors that opened to Kunsang’s flat would be pitch-dark. With water dripping from my umbrella, I’d feel my way down that darkened passage and rap my knuckles on the unseen door at the end.

The room we met in was his bedroom as well as the family shrine and living room. Images from the Tibetan Buddhist pantheon and portraits of important Nyingma lamas draped with ceremonial scarves hung from nails along the walls. A TV stood in one corner, in front of the family altar, which glowed in the semi-darkness from the light of a single butter lamp. That lamp and the faint light coming through the windows were usually the only light by which we’d meet, for monsoon wreaked havoc with electrical lines. More often than not the electricity would be out in the whole of Darjeeling.

Kunsang would usually be sitting cross-legged on his bed when I arrived with an unbound Tibetan scripture open before him. He’d be chanting from the book, only briefly looking up as I came in to indicate the bolstered bench opposite where I always sat. When through, he’d get up. Still chanting, he’d light a small fire of paper and wood in a convex pan that might have once been used to make chapattis, or flat breads. He would blow on it with a short pipe to get the embers glowing, then put into it the pine boughs known as

sang

, which let off billows of fragrant smoke. Opening the window he’d place the burning incense on to his neighbor’s tin roof, which was immediately outside his window and protected from the rain by his own—such is the jumble of roofs in the Darjeeling market. All the while he’d be reciting a mantra while the white smoke merged with the low cloud in which the city had been immersed for days.

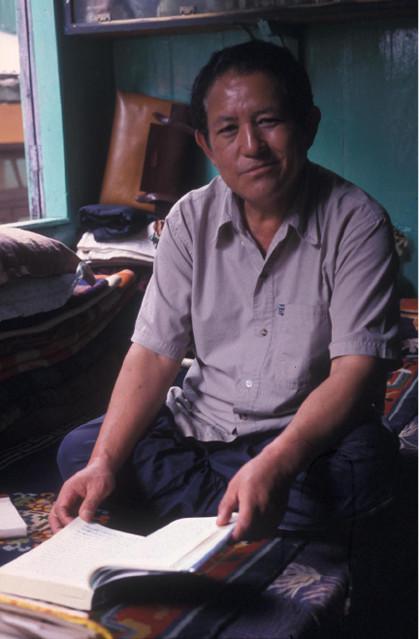

Kunsang, in his room in Darjeeling

When he was through with his ritual, he’d carefully wrap the book in cloth, tie it with a colored ribbon, stand up on his bed and tuck it into a shelf. Then he’d sit back on his bed with a huge smile, his gnome-like ears protruding from his head, and start laughing even before anything was said.

‘So,’ he’d exclaim, ‘and

then

what happened?’

Over the course of innumerable afternoons he told me his father’s story from beginning to end, sometimes starting at the end and working forward or backing me through fantastic episodes until I nearly knocked into reality.

Shortly after my arrival his daughter Yeshe, or more often his son Wangchuk, would arrive. They were in their twenties, spoke English well and took turns acting as my interpreter, thereby learning about their grandfather’s life and the unusual way their father had grown up.

Tea would be brought by Kunsang’s wife who often sat on the bed opposite and listened quietly to her husband’s tales except when the story became just too funny, and we’d all be laughing with no way to stop.

Sometimes it was the Tamang Tulku, a boy of eight or nine, who brought us the tea. Tamangs are a Buddhist people from high in the Nepal Himalayas, near the Tibetan border. He was the

tulku

, or reincarnation, of a lama, though probably not a very high one. Because the Tamang Tulku was born into a family so poor they could not afford to put him in a monastery for special training, Kunsang agreed to take him on. Living with the family, he was a cross between an honored servant, a son and a full-time clerk at the two clothing stalls they owned in a small brick shopping complex whose sign brazenly declared it ‘A Shoppers’ Paradise’. In exchange for taking him in in such a capacity, Kunsang was teaching him to read and write Tibetan, as well as giving him instruction in the dharma. It was only much later that Kunsang told me that the boy wasn’t really a

tulku

, or reincarnation. I never could tell. After that I called him the Tamang non-Tulku.

Kunsang is a layperson; he does not shave his head nor does he wear a robe, except on special occasions when he wears the white robe of the tantric practitioners known as the

nagpas

. Yet he is considered by many to be a

rinpoche

. Rinpoche, meaning precious one, is the term Tibetans reserve for their high lamas. Kunsang is known as the Dungsay Rinpoche, the title used for the son of a high lama.

The special and almost mediumistic ability

lingpas

have to enter a timeless state and bring something back into time—be it a teaching in the form of

ter

, or treasure, or directions to a hidden valley—is often passed on from father to son. Tulshuk Lingpa’s father Kyechok Lingpa had been the first in the line, and there was some expectation that Kunsang would follow. Having grown up as Tulshuk Lingpa’s son, he certainly has the knowledge and experience and no doubt the education; yet Kunsang would be the first to say that he lacks that rare and special ability, which can only be given by fate and which defines the true

lingpa

.

Though not a

lingpa

, Kunsang’s knowledge of the dharma—or Tibetan Buddhist teachings—is both vast and deep. Because of this, and because of his father, he has had much contact with and has taken initiation from some of the highest lamas of the day. Though devoting his life to a large extent to the dharma, he was also in business for many years. Now that his children and the Tamang Tulku have taken over the daily running of the family clothing stalls, he devotes himself even more fully to the dharma, with much of his day spent sitting cross-legged on his bed with an open

pecha

, or scripture, before him, white clouds of

sang

billowing to the heavens outside his window as he performs rituals for himself and his family as well as for others.

Many people come to him for teachings and to request him to perform rituals on behalf of the ill. He dispenses precious waters and other substances sanctified by ritual. Often when I arrived, there’d be others in the room listening to him discourse on some aspect of the dharma or making offerings so he’d perform a ritual for a dear one. At times, they brought sick people to him; he’d listen to symptoms, consult astrological calendars, dispense Tibetan medicines and herbal teas, and on the basis of the faith they had in him, offer them the strength to heal themselves.

Once, after the son of an old Tibetan man who was very ill had left with his little vial of blessed water, Kunsang said, ‘What to do? When they come, I must do something. Though sometimes I’m busy, busy—too busy! My father was offered many monasteries. Me too. But I’m not interested. If you have your own monastery, when someone dies you have to go and do puja for the whole day. And not just one day. When people get sick, it’s all the time people saying, “Rinpoche, hurry. Hurry!” And what to say? You have to go.’

Another time Kunsang said to me, ‘The Tamang people told me, “You are very well educated and you are very good inside. You are a very high lama’s son. So we are offering you our monastery.” But I said “No, no, no.”’

‘This type of job—I don’t like. But then they said, “Rinpoche, if you have a big monastery, you’ll be a big lama with many disciples.” That’s what the Tamang people said. But one month has thirty days. With my own monastery, in all those days not one single day would be empty, not one moment free. This kind of job I find very

boring

.’

CHAPTER THREE

CHAPTER THREE

Eloping over Mountain Passes

Tibet, while maintaining its place on the map, has the reputation of being a hidden land of spiritual understanding. Though exaggerated in popular imagination, this reputation has been earned by Tibet’s centuries-old vast isolation and the high attainment of its spiritual masters, considered by many to be the world’s most advanced. Where better to look for a tradition of a hidden land than to that land which until recently has to the rest of the world itself been hidden? Arguably the most isolated country in the world until 1959, by its very isolation Tibet managed to guard precious pearls of ancient wisdom.