A Step Away from Paradise: A Tibetan Lama's Extraordinary Journey to a Land of Immortality (15 page)

Authors: Thomas Shor

Terton

opening a beyul with a

khandro

(notice ritual implements behind opening).

Temple wall painting, Tashiding Monastery, Sikkim

‘Had they met before?’ I asked.

‘Certainly,’ Kunsang replied. ‘She and her entire family had been disciples of Tulshuk Lingpa for a long time. They had known each other of course but he didn’t know she was the

khandro

.’

‘How did your mother feel when your father took another wife?’

‘Angry,’ Kunsang said, ‘When a second wife comes, won’t there be a problem? Sure—of course!’

‘How did

you

feel when your father took another wife?’

‘I was not happy,’ he replied. ‘But then my father’s disciples came to me and to my mother too. They told us that it was written in the scriptures that to open Beyul he needed a

khandro

. This was supposed to happen. It had to be. They told us not to get upset.’

Another time, Kunsang told me, ‘I don’t know whether my father had many girlfriends but a lot of women fell for him. He was good-looking.’

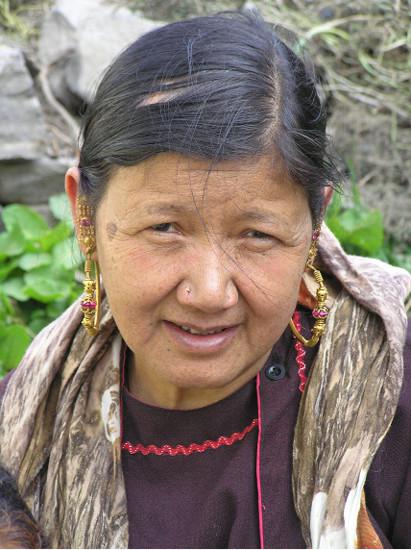

I met Tulshuk Lingpa’s second wife, Khandro Chimi Wangmo, who lives in a house across a dangerous ravine from Simoling Gompa. I went there with her and Tulshuk Lingpa’s grandson, Gyurme, who was accompanying me on my trip to Lahaul and acting as my interpreter. As we negotiated the treacherous slope to his grandmother’s house, Gyurme told me that it would be impolite to ask her anything personal whatsoever. When we arrived at the house, she came in from the fields where she was busy planting potatoes to speak with me. She was reticent and anxious to return to her potato fields. It was clear she didn’t want to speak of earlier times.

Khandro Chimi Wangmo posing with a stuffed snow leopard that had recently broken into her cowshed, seriously injured a cow, was half killed by the cow’s kick, and then finished off with a bullet.

When I asked Rigzin Dokhampa, the researcher at the Namgyal Institute of Tibetology outside Gangtok, about the role of the

khandro

he told me the following story.

There was a terton in Tibet. One day he went with his

khandro

to a rugged mountain area in order to find

ter

.

Tertons

are like that. You cannot find the logic. They wake up one morning, and they know today is the day. Maybe they have a dream; maybe they receive a vision. But they know today is the day they’ll find a text hidden by Padmasambhava a thousand years back in a particular rock face of a twisted mountain they’ve never seen. They’ll tell their disciples; they’ll warn them, ‘Whatever I say, don’t contradict me. Say OK, OK. I may ask for the impossible. But do not doubt. Whatever I do, do not doubt it.’ To find

ter

isn’t as easy as knowing where it is, going there and taking it out of a cleft in the rock, as if it were a manuscript that was hidden there. To take out

ter

is to reach into another dimension and bring a piece back.

So this terton went with his

khandro

beyond any trail, into the tangled mountains where neither of them had been before. They climbed narrow cliffs and razor-like fissures until they reached a place where the huge stone mountain they had ascended ended abruptly in a sheer cliff of a size and magnitude that was hardly imaginable. Far below, a river cascaded over a series of raw waterfalls. On the other side rose a cliff every bit as sheer as their own but higher, dwarfing them and blocking the sun. A cold wind blew up the chasm.

The terton stood on the edge of the abyss. He held out his hand and pointed across to a fold in the rock on the cliff face opposite. ‘The

ter

is there,’ he said.

The question, of course, was how to get there. It was as impossible to descend to the river as it would be to climb the other side.

Even

tertons

can experience doubt.

The

khandro

sensed the seed of doubt in the terton’s mind even before it surfaced. She ran up behind him, yelling out ‘Get the

ter

!’ and pushed him off the cliff.

There was a huge vulture flying below them. The terton landed on it. It brought him to the other side, and he took out the

ter

.

Tulshuk Lingpa used to perform a special form of divination, called the

trata melong

, in which he stuck a convex brass mirror into a bowl of rice, performed a ritual, then invited people to look into the mirror to see if in the dull shine of the burnished brass they saw any images, which he would then interpret. The ability to see in the mirror is known as

tamik

, which literally means picture eye. Those with

tamik

have the ability to see images that predict the future, unravel mysteries of the past, and communicate messages from the spirits. Though it was not unknown for older people to have this mysterious ability, it was usually children who could see, especially girls. In them, it seems, the intuitive channels were still open and the active imagination stronger.

Rigzin Dokhampa recalled how Tulshuk Lingpa used to perform the

trata melong

ritual at Tashiding. ‘Not only girls can see in the mirror,’ he said. ‘I was a child when Tulshuk Lingpa was in Tashiding, maybe fifteen, sixteen. He used to go to one of the temples at the Tashiding Monastery with the local children to perform this ritual. I would be there, my brother would be there—and maybe thirty other children, both young monks and lay children also. He did this many times. It was something we children could participate in, and we’d all be very excited. He would do the ritual, push the mirror into the plate of rice and have each of the kids look into the mirror one after the other. Then he’d ask us what we saw. Some could see; others couldn’t. It was a special ability.

‘One time when my turn came, I looked into the mirror and after some moments the mirror disappeared and in its place there was a beautiful large mountain with many streams of water flowing down it. I saw huge stupas on the mountain and long prayer flags. On top of the mountain snow was falling. On the right side, there was a wide trail rising with the slope of the mountain, which was washed away in places. I told Tulshuk Lingpa what I saw, and he said the stupa and prayer flags were good signs. But the parts of the trail washed away—that he said was not so good. Other children saw yaks, sheep, mountains—like that.’

Of everyone who ever looked into Tulshuk Lingpa’s

melong

, or mirror, Khandro Chimi Wangmo’s younger sister, Yeshe, was by far the most gifted. Though Yeshe could neither read nor write, she had

tamik

. She was often employed by Tulshuk Lingpa to look into the mirror, even before they went to Sikkim. Though a teenager and married at the age of sixteen, she was also destined to become Tulshuk Lingpa’s

khandro

, and her fate was closely wrapped up with his.

Yeshe

One morning when Tulshuk Lingpa was living in Pangao, a rich Indian merchant braved the treacherous slope to his cave to plead for his help. He was in a panic particular to a rich man who has just lost everything.

‘Help me, please!’ he implored. ‘My safe was just stolen with everything in it—everything I have—and the police can’t find a single clue.