A Song Called Youth (3 page)

Read A Song Called Youth Online

Authors: John Shirley

Tags: #Action & Adventure, #General, #Science Fiction, #CyberPunk, #Military, #Fiction

Smoke was thinking that the starved bear should have the big Weatherby, and the green-eyed one should have the .22, because he was smaller, and because he was the leader, so he should have known better. But maybe the gun was the totem of power here. And the king should carry the scepter.

“Here’s where I take a chance,” Smoke said. “I’m going to refuse to tell you my business. Except to say it’s no threat to you.”

The starved bear took a step toward him, and Smoke closed his eyes and said, “I hope they don’t hurt my crow.”

Not sure if he’d said it out loud.

“Jenkins,” the green-eyed one said, not very sharply. But that’s all it took. The big guy stopped, and Smoke, even with his eyes shut, knew the starved bear was looking at the green-eyed one for his cue.

“Lez go through his stuff,” the vulture said. “Might be food.”

“Animals,” Smoke said, opening his eyes. “One’s a starved bear and one’s a vulture, and you make me think of a coyote or a wolf.” He looked at the leader. Again the guy made the smile that didn’t travel to his eyes.

“You’re just a roost for a crow,” he said. “You got a name?”

“Smoke.”

“I heard about you, something. Like you barter, black market or . . . ” He shrugged. “What’s to be so mysterious about?” Smoke didn’t answer, so the guy went on, “What’s your crow’s name?”

“I haven’t decided. We’re of recent acquaintance. I’m wavering between naming him Edgar Allan Crow or Richard Pryor.”

The green-eyed one lowered his rifle, maybe only because it was heavy. “Edgar Allan Crow is corny. What’s ‘Richard Pryor’ mean?”

“He was my father’s favorite comedian, and he was black. That’s all I know about him.”

“We could eat that bird,” the vulture suggested. He looked at the green-eyed leader. “Let’s eat the bird, Hard-Eyes. Fuck it, huh?”

Hard-Eyes.

Quite a monicker.

Hard-Eyes said, “No. Crows are good luck where I come from.”

The clouds had congealed into rain and the rain had wormed and nosed and nudged its way into the high-rise’s ten thousand hairline cracks, and it was seeping out of the cracks in the ceiling and dripping with a smell of dissolved minerals into a large bathtub—which someone had dragged from its original mooring just to catch the rain—and into a wooden box which itself was beginning to discolor and leak.

The crow was asleep on Smoke’s shoulder.

“I wisht we could have a goddamn fire,” Pelter was saying. Pelter was the vulture.

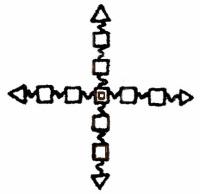

They were sitting on red plastic crates around a dead TV set. The TV screen had been painted with a symbol:

. . . in red paint. They weren’t looking at the screen. But it was a kind of chilled hearth for them. They’d eaten a tin of sardines and a pound of cheese Steinfeld had given Smoke “to soften them up.” Smoke had brought it out as soon as they’d arrived at the squat. “This’s our squat,” Hard-Eyes had said, just as if he’d wanted to displace the word

bivouac

in Smoke’s mind, in case Smoke was working for the Armies after all.

There was a jumble of old furniture in the room, mysterious geometries in the half-darkness. They’d blacked out the window with three thicknesses of taped-on black plastic; the plastic’s wrinkles made glowworms of the anemic yellow light from the two chemlanterns. Smoke said, “You’re gonna need a new lump for your lanterns. That solid fuel seems like it’s going to last forever, then all of a sudden you’re in the dark.”

“I don’t like the way this guy talks,” Pelter said. “He’s gonna bring us bad luck.”

Hard-Eyes ignored Pelter. He looked across the cone of lampglow at Smoke and said, “You’re not talking just about lamp fuel.”

Smoke shrugged. “It’s all in the lanterns. Energy and attrition and entropy.”

Hard-Eyes blinked, looking skeptical. Then his face cleared and he nodded. “And glass going black.”

Jenkins and Pelter looked at one another, then at Hard-Eyes and Smoke and then at the floor.

“What’s the TV fetish-sign about?” Smoke asked.

He nodded toward the red symbol on the screen. He’d seen it the first time in Martinique, ten years before. He’d seen it on pendants and on screensavers. No one had explained it, except to say, “It’s good luck.” Later, in Harlem, seeing dead TVs turned into household iconography, he’d figured it was big-city cargo cultism, in a way, and something more: an invocatory variation on the Gridfriend sign.

“You believe in Gridfriend?” Smoke asked.

Gridfriend, god of the global electronic Grid. The Grid gives TV, and news—and credit, which translates into food and shelter. Pray to Gridfriend and maybe the power company’s computers lose your bill, and you go an extra month before they turn off your lights; pray to Gridfriend and maybe Interbank makes an error in your favor, computes you five hundred dollars you shouldn’t have. And then forgets about it. Pray to Gridfriend and the police computer loses your records. Or so you hope.

“That’s not the Gridfriend totem,” Hard-Eyes said. “It’s Jenkins’ thing. It’s Jenkins’ invocation to the Big Organizer, the god who manufactures patterns—and luck. Jenkins used to do a lot of meth.”

“Big Organizer? Just another Gridfriend. You a believer in luck?”

“I make my own.”

Smoke smiled at the movie-melodrama sound of “I make my own.” It went with the monicker.

“That’s why you’re here, Hard-Eyes? In this fucking icebox?”

Jenkins snapped Smoke a look. “Hey, you got nothing better goin’, Rags. You ain’t even got lanterns. You shouldn’t be talkin’ about our lanterns, man.”

The crow stirred on Smoke’s shoulder, disturbed by Jenkins’ tone. Smoke crooned to it. It tucked its head back under its wing.

He smiled. “Look at that. That’s completion . . . This crow and I met today and we’re fast friends already. Just like that. Makes me almost believe in reincarnation.”

“We should eat ’im,” Pelter said, wiping a trail of snot from his bony nose with a crusted sleeve. His eyes were red, swollen, and he coughed sometimes, and now and then his head dipped as if he might fall asleep sitting up. Smoke thought Pelter was sick and would die soon.

“The bird will more likely be pecking your dead eyes out,” Smoke said, and then regretted it. He hadn’t intended to say it aloud. But Pelter didn’t hear. His head had drooped and he was breathing with a bubbling sound.

Jenkins was scowling. “You hear that, Hard-Eyes? His bird pecking Pelter’s eyes?”

Hard-Eyes shrugged. “Smoke resents people talking about roasting his designer squab. Makes a man say bitter things.”

Smoke laughed. Hard-Eyes made the short, snorting sound that passed for machismo laughter. But his eyes stayed hard.

As the rain made hollow

plips

in the tub of water.

Jenkins and Pelter were asleep, stretched out on pallets of cardboard. Jenkins slept with his face in his curled arm—like the crow with its beak under a wing—his hands now and then clutching, closing on something he dreamt about; Pelter slept with his mouth open, his breath coming raggedly.

There was only one lantern still lit. As if Smoke had spoken an omen, the other one had used up its fuel and gone out, just like that.

“Not going to make it,” Smoke muttered.

“The other lantern?” Hard-Eyes asked.

“Pelter. Maybe the lantern too.”

“Pelter’s been sick,” Hard-Eyes said, nodding.

“Been with you long?”

Hard-Eyes shook his head. “Six, seven weeks. Jenkins has been with me longer. Jenkins, he’s not dumb. Just a different focus. He’s handy with chip-splicing, accessing, like that.”

“Not much use for computer skills in Amsterdam just now.” They both smiled wearily at that; it had been too obvious a thing to say and they both knew it.

“You still worried about me?” Smoke asked.

Hard-Eyes shook his head. He smiled flickeringly. “The crow vouched for you.”

“I’m a little worried about

you.

You could almost be one of their background men. Looking for the underground. Or for anybody that smells like they wish the Armies would snuff each other and fuck off.”

Hard-Eyes shrugged. “You want the story?”

Smoke nodded.

So Hard-Eyes told his story.

I was in London, (Hard-Eyes said), and I was at a club called The Retro G. They were into cultural retrogressing. That month they had a ska motif, ska music. Two months before they’d had thrash. And before that it was hard core and before that worldbeat and before that angst rock, and before that it was dub and before that it was core-dub and before that, melt-pop, which is what was hot when the club opened. If the club were still there I guess they’d have worked back through the nineteen-nineties, eighties, seventies, sixties, back to rockabilly and bebop and blues. But it’s not there now because that part of the town is rubble. Me, I’m from San Francisco, California. I was in Britain for a seminar on Social Democracy. Watered-down socialism. I was a grad student. Yeah, a student with a fucking satchel for carrying his books. Political science major. And deep into applying structuralism to problems of diplomacy. Jesus. And then politics got real for me. The truth behind politics. Aggression and acquisition . . . We were at the Retro G, dancing, and the DJ sliced in that meltpop tune, “Dancing with the Russian Brothers,” not part of the ongoing retro motif, so it made you wonder, and then the DJ said it was dedicated to the Russian Brothers who’d just driven their tanks across the frontier into Poland. It shouldn’t have been all that surprising; the Ukraine, Belarus, Kazakhstan—it’d all been reunited into Greater Russia not that long before, and did we really think they were going to quit there? But still, we thought he was kidding, until we heard someone else talking about a radio broadcast and we went outside to Dody’s car. Dody—man, what an airhead. But she was worried about her business because she marketed designs from some Polish designer. And on Dody’s car radio they said the Greater Russian army appeared out of nowhere, no one could understand how they got so many troops to the border without alerting NATO. It was a long time before word filtered back about the maxishuttle drops out of orbit. NATO saw the drops, but the Russians told them it was emergency medical supplies because of some outbreak, and then the fucking troops were in place . . . Okay, that’s the version I heard. You hear different versions . . . Anyway, they took Warsaw, moved the Greater Russian Liberation Army’s western front HQ in. And this girl Dody, all she could think about was her business going down the drain. I wanted to stuff her up the exhaust pipe of her Jaguar Gasless.

But after that, I was no better. All I could think about was covering my own ass, getting back to the States. Only, you couldn’t get a flight out of London, they were all restricted for government use or booked solid. Everyone wanted the fuck out of Europe. You ever read about the Vietnam war? Right, well, you know how when the NVA moved in at the end, there was this rabid scramble to get out of Saigon on anything that moved, people running to cling to the runners of choppers . . . It was like that for a whole continent, in the big cities . . . I went to the airport and some guy was scalping the airline tickets, wanted twenty-five thousand quid each. People climbing over people to buy from the motherfucker . . . People clamoring at the embassy demanding help and getting thrown out and finally breaking windows, getting shot at . . . At the airport somebody once an hour tried to pull off a hijacking . . . it was worse at the docks. But I found a dude with a boat was on his way to Amsterdam, said he knew somebody had a private jet there, could get us both on, and for some reason I bought the story. I was panicked. Yeah, you laugh

now.

He got me to Amsterdam and took my money to “make the connection” for us, and then he never came back, of course. The money wasn’t worth much, anyway. But I found him, eight months ago, and he had this Weatherby, he’d looted it from somebody’s house. Never gave him a chance to use it on me. I used the twenty-two on him first . . . But wait, I left out a lot. Only, you were probably here for what I left out. NATO forces declare martial law in Holland, Russians move in, Russians get driven back. The riots. The public executions and the riots because of the public executions and then more executions. Me, I watched it all from up here. Tried to stay out of it.

But I’ll tell you something funny. It was almost a relief to me. The whole thing. Even the war. It was like—before the war, nothing was real. I mean . . . people talked about things that happened in download movies and VR and online RPG, like they were anecdotes about people they actually knew and . . . It was like our lives before the war were just long, detailed movie lives or TV lives or VR lives . . . I can’t explain. But I had this feeling that nothing was real and nothing mattered until the war.

Anyway, I was living with a Dutch girl, Luka. How I met her, she went out one day to try to buy some food, and there was a food riot and she was attacked because she had a bag of food—I’d been in line with her, and when the riot started I helped her get away from it and she was grateful, so she gave me a place to stay—well, okay, maybe it wasn’t just gratitude, she was lonely—and it was pretty much an instant thing, like we’d always been shacked up; there were no further questions. She had hair that looked like . . . you ever see cornsilk? She was a big girl, but handsome, Amazon handsome. Always neating things up. Maternal, like your aunt, except in bed. She was . . . And then of course after the Russians blockaded the port and the siege started, the food riots spread from the market to the high-rises. The masses, you know, usually have the wrong idea about who’s pulling what strings, and they thought the people in the ’rises were hoarding food, which was bullshit; Luka and I had to stand in the same ration lines as everyone else, but there’s no reasoning with hungry people. And they came in and tore the place apart and . . .