A Scots Quair (71 page)

Authors: Lewis Grassic Gibbon

p.169

the Reisk

. An upland area between Arbuthnott and Mondynes. The croft of Bloomfield where Gibbon lived between the ages of eight and sixteen was on the Reisk road, two miles n of Arbuthnott.

Geyrie's moor

. The hill of Gyratesmyre and the farm of that name are just south of Bridge of Mondynes on Bervie Water.

p. 170

Barras slopes

. About three miles inland from the coastal village of Catterline.

p. 172

the Wairds

. Upland farms and moorland about 1 mile se of Gyratesmyre.

p.173

he lived in London and wrote horrible books

. A sly reference to Gibbon himself and his disapproving mother.

Bervie

. Inverbervie, ten miles s of Stonehaven. Like the Segget of the novel, it mainly consisted of three small irregular streets forming three sides of a rectangle. It had woollen, flax, and tow mills, as well as wincey and sacking factories (ogs).

p. 177

Grieve

. Christopher Murray Grieve (âHugh MacDiarmid', 1892â1978), poet, essayist and publicist, was the dominant figure in Scottish literature from the mid 1920s to the 1950s. During the time-span of the novel he had sat on the Montrose town council as an Independent socialist, and was at various periods a member of the Scottish Nationalist and Communist Parties.

Compton Mackenzie

(1883â1974), popular novelist and publicist, was a founder-member of the Nationalist Party. Gunn. Neil Miller Gunn (1891â1973), novelist and excise- officer, joined the Nationalist Party in 1929 and had campaigned actively in 1931 for John MacCormick, Nationalist parliamentary candidate for Inverness-shire.

Lord Loon of Lossie

. James Ramsay MacDonald (1866â1937) was a native of Lossiemouth, a fishing port on the Moray coast. He had been prime minister of a minority Labour government in 1924, but now (1929) had a parliamentary majority. In 1931 economic collapse and massive unemployment caused him to combine with the conservatives to form a âNational' government to solve the crisis.

p. 179

A man's a man for a' that

. Hairy Hogg perverts the revolutionary message of the song.

p. 183

his heart was in the Highlands

. The reference is to a song by Burns, âMy heart's in the Highlands, my heart is not here;/ My heart's in the Highlands, a chasing the deer.'

p. 188

sailing ships

. In Gibbon's Diffusionist mythology, these contained the bearers of that corrupt, enslaving civilisation

p.188 that had spread northwards from Egypt, destroying the idyllic life of the primitive hunters.

p. 190

banking and braeing

. The reference is to Burns's âYe banks and braes o' bonie Doon', with a pun on âbrae' (bray).

Frellin

. There is no such village in the Mearns, but Gibbon may have taken the name from the old pronunciation of Freeland in the Forgandenny parish of se Perthshire.

p. 198

Means Test

. The National Government reduced unemployment benefit by some ten per cent. After a claimant had been twenty-six weeks on benefit the income of the entire household was examined by the local Public Assistance Committee. All forms of incomeâpensions, contributions from sons and daughters, even household possessionsâ were taken into account (John Stevenson and Chris Cook.

The Slump

, 1977, p. 68).

cut off the Bureau

. His dole had been stopped.

p. 199

Mearns Chief.

The local paper's name was, and still is,

The Mearns Leader and Kincardineshire Mail

.Â

Naomi Mitchison

. Novelist, social critic and travel writer (b. 1897). Her anthropological and historical novel

The Corn King and the Spring Queen

had just been published (1931).

p.208

rock of Christ's kirk

. âThou art Peter, and upon this rock I will build my church; and the gates of hell shall not prevail against it' (Matthew xvi. 18).

p.211

It is Finished

. (John xix. 30).

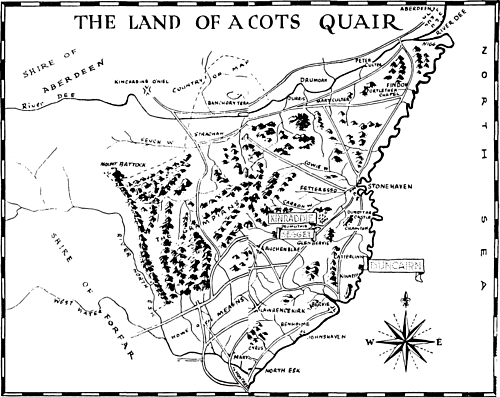

To

Hugh MacDiarmid

The âDuncairn' of this novel was originally âDundon'. Unfortunately, several English journals in pre-publication notices of the book described my imaginary city as Dundee, two Scottish sheets identified it with Aberdeen, and at least one American newspaper went considerably astray and stated that it was Edinburghâfaintly disguised.Â

Â

Instead, it is merely the city which the inhabitants of the Mearns (not foreseeing my requirements in completing my trilogy) have hitherto failed to build.

L. G. G.

When

Grey Granite

was published at the end of 1934 it was advertised as the last volume of a trilogy. Yet many who had missed the first two novels were swept off their feet when they read it. This seems to have been the experience of Tom Wintringham, the influential editor of

Left

Review

, who termed it âthe best novel written this side the Channel since Hardy stopped writing'.

1

And it was certainly that of the

Sheffield Daily Telegraph

reviewer, who was glad he had not come across the earlier volumes because, after the overpowering experience of

Grey Granite

, the âpleasure of their first perusal' was still to come (31 January 1935). Page Cooper of Doubleday (Gibbon's American publisher), who did of course know the other books, could not keep it out of her mind and found it âa bigger, more disturbing, and beautiful book than

Cloud Howe

. One hesitates to label anything with the word genius, but there isn't any other for the quality of his mind.'

2

Of those who went in for comparisons, the

New York Times

reviewer was almost as enthusiastic, calling it âGibbon's most swiftly moving book and most adventurous in ideas' (3 February 1935). More significantly, perhaps, Gibbon's greatest Scottish contemporaries, Hugh MacDiarmid and Edwin Muir, both liked it: MacDiarmid enthusiastically, Muir less so (though he preferred it to its predecessors).

3

The majority of those who had read all three parts seem to have agreed with the

Glasgow Herald

in the judgment that is still, I think, standard among âcommon readers': â

Sunset Song

stands by itself, a good novel;

Cloud Howe

and

Grey Granite

are two rather ramshackle outhouses which have been added to it.' This, however, is to forget that Gibbon had planned a

trilogy from the first,

4

and to ignore the fact that each of the outhouses has its own effective structure, however different from nineteenth-century and Edwardian norms. Like all creative writers Gibbon had not worked out the total shape right at the start; once begun, the novels flowed with their own momentum and took on new features as he wrote. That his original title for

Cloud Howe

was

The Morning Star

indicates that he cannot at first have thought of organizing it around contrasting cloud-formations passing over the vale of the Mearns, but perhaps around heavenly bodies ironically conceived. And when he came to grips with

Grey Granite

he scrapped his original plan of a Prelude that would make the beginning of

Grey Granite

formally parallel to those of the earlier novels, with their milieux firmly set in place and time (this is given in the Appendix). The result is that Duncairn has depth, history, and background only for those in the know; for them, Gibbon's city is more like Aberdeen than Dundee, Glasgow or Edinburgh, and the glancing identifications and allusions provide, quietly and unobtrusively, many of the in-jokes of which Gibbon was so fond.

5

For the wider readership, Duncairn is an imaginary city, the crumbling backdrop to the personal and political paradigms set within it. The novel has thus a much freer form than

Sunset Song

, framed by Prelude and Epilude; its frame consists of two passages about Chris, where interior monologue deftly incorporates third-person narration. With the first, we begin

in medias res

with Chrisââold at thirty-eight?'âpuffing and panting as she lugs her groceries up the urban height of the Windmill Steps, and end with her in the countryside, above the croft she has âretired to', enigmatically losing consciousness on top of the Barmekin.

When Gibbon began

Sunset Song

he told his wife the whole trilogy was to be written round âa woman',

6

and the framing just mentioned seems to show that this is as true of

Grey

Granite

as it is of the earlier novels. But Chris, though as moving and convincing as ever, is in a sense peripheral to the main action, the growth and development of her son Îwan, which parallels and contrasts with her own rural adolescence

in

Sunset Song

. The book's four sections are called after different constituents of granite: Epidote (a greenish silicate of calcium, aluminium, and iron), Sphene (whose crystals are wedge-shaped and which contains the element titaniumâstrong, light, corrosion-resistant), Apatite (consisting of calcium phosphate and fluoride), and Zircon (âa tetragonal mineral, of which jacinth and jargoon are varieties'âjacinth is reddish orange, and jargoon brilliant and colourless). They mirror the stages in Ewan's transformation into the kind of person required by the stark, sure creed that will cut like a knife:

Cold and controlled he had always been, some lirk in his nature and upbringing that Chris loved, who so hated folk in a fuss. But now that quality she'd likened to grey granite itself, that something she'd seen change in Duncairn from slaty grey to a glow of fire, was transmuting again before her eyesâinto something darker and coarser, in essence the same, in tint antrin queer.

Gibbon's theme reflects one of the commonest spiritual sequences of the thirtiesâthe process whereby a bourgeois intellectual came to join the Communist Party and decided to give over his life to it. Many have felt with Isobel Murray that âthe greatest weakness of the book is the character and role of Ewan';

7

others have seen in him its main strength. That was certainly Eric Linklater's view before he had even finished it. He has left a unique record of his immediate responses in a letter written towards the end of 1934:

Chris, I think, has lost a little of the characterâbut she's lost it to Ewan, who's coming very robustly alive; & the curious angular growth of his mind is very true to type. So far I can sympathise with his nascent politics very comfortably, & if the police had behaved in that manner his bottle-throwing would have been not merely noble, but natural.

8

The function of the granite symbolism is to highlight Ewan's willed transformation into the âmore than human': Ewan comes to be like granite just as Stalin means steel and

Molotov means hammerman. He inherits from Chris a still centre, a refusal to be anything other than himself, an aloofness that others find unsympathetic and haughty. He respects what Gibbon sees as the cool detachment of science and is utterly blind to the arts; his sense of humour is, to put it mildly, limited, and at one point Chris says, âhuman beings were never of much interest to him.' Yet it would be wrong to say he is emotionless; it is merely that he can keep his ordinary feelings under controlâhis admiring affection for Chris, his detestation of what breeds nauseous slums and stunts the wretched of the earth, his contempt for the inchoate, the indecisive, and the second-rate. His most intense emotions are those of the communist mystic, which come on him towards the end of the novel, an essentially religious identification with the enslaved and the exploited throughout recorded history. They are only made possible by what Ewan learns in the factory, the working-class movement, and the police cell, but they are rooted in a character trait he displayed even in boyhood, in his friendship for Charlie Cronin the spinner's son and his strange bond with old Moultrie, survival from an age of pre-industrial knacks and skills, who on his deathbed shared with Ewan the precious essence of the old ways (

Cloud Howe

, Canongate Classics edition, p.192). They also link him to Chris and show that despite his crystalline hardness, his sensibility is akin to hersâto the Chris who in her girlhood saw visions of prehistoric hunters and farmers and identified with the tortured Covenanters in the Whigs' Vault at Dunnottar.

William K. Malcolm, in what is perhaps the best critical presentation of Ewan to date,

9

draws attention to his literary precursors in the Soviet Pantheon, and links him to the Russian and international debate over the nature of the Communist Hero and how to present him. He sees Gorki's

Mother

(1906) and Gladkov's

Cement

(1925) as the most important analogues, and Ewan's brusque rejection of Ellen as being in their tradition, where âthe protagonist demonstrates his heroic fortitude ⦠by resisting the threat made to his greater political destiny by romantic involvement'

(p.161). But it is not strictly correct to speak of a âsocialist realist' influence here: the dogma was not theoretically formulated until 1934, and therefore could have had no influence on either

Mother

or

Cement

. Orthodox communists have always criticized Gibbon's presentation of Ewan. They have felt that the ideal communist leader should be warm, sympathetic, many-sided, and richly humanâall the things that socialist realism said he should be, and which Ewan is not. His coldly analytic mind drives him to extreme and âsuper-revolutionary' conclusions, to âan intellectualized and at times inhuman conception of the workers' struggle for Socialism', and his remarks on tactics do not in the least resemble the real communist tactics of the time; they are pure fantasy on Gibbon's part.

10

But the whole course of history since 1934 seems to show that they were not fantasy. The book is dedicated to Hugh MacDiarmid, and as early as 1926, in the

First Hymn to Lenin

, MacDiarmid had proclaimed that the horrors of the Cheka were not merely necessary but even insignificant when compared with the role of Death in the whole Cosmos, and had asked

what maitters't wha we kill

To lessen the foulest murder that deprives

Maist men o' real lives?

Solzhenitsyn has shown how the Leninist Cheka was a precursor of the Yezhov terror, and it is only a step from MacDiarmid's lines to âWhat maitters't what lies we tell, or how we deceive the poor lumpen proles?', since we, whatever our actual social origins,

are

the working class, and

our

will is the âreal will' of the proletariat, whether they know it or not. Jim Trease makes the point, at first grimly joking:

For it's me and you are the working-class, not the poor

Bulgars gone back to Gowans

. And suddenly was serious an untwinkling minute:

A hell of a thing to be history,

Ewan

⦠A hell of a thing to be History!ânot a student, a historian, a tinkling reformer, but living history oneself, being it, making it, eyes for the eyeless, hands for the maimed!â

Or again, when Ewan is with Trease and his wife:

[He] liked them well enough, knowing that if it suited the Party purpose Trease would betray him to the police tomorrow, use anything and everything that might happen to him as propaganda and publicity, without caring a fig for liking or aught else. So he'd deal with Mrs Trease, if it came to thatâ¦. And Ewan nodded to that, to Trease, to himself, commonsense, no other way to hack out the road ahead. Neither friends nor scruples nor honour nor hope for the folk who took the workers' road â¦

In 1934 fascism seemed in the ascendant in Europe, and possible even in Britain. Beyond the novel's open end there lies for Ewan, as Gibbon saw it, a brief spell as a full-time communist organizer and a long period when he would âhunger, work illegally, and be anonymous', through âa generation of secret agitation and occasional terrorism'. As things actually turned out in Britain and the world, Ewan might well have fought in Spain with the International Brigade, then spent several years as a industrial organizer in Scotland and the English midlands before ending up as one of the leaders of the British Communist Party. But in both the Ewan-Trease vision of a fascist Britain and the âreal' future, Ewan would have had to live through the Moscow trials and the Stalin purges: he would have had to justify what he knew to be false in the interest of what his theory told him was the lesser evil. Many communists tricked themselves into believing that the accused were always guilty, that there were only a very few labour camps, that socialist planning in the East was economically successful. Ewan, as Gibbon presents him, would have faced up to the truth in private and deliberately suppressed it for the public. And if the communists had come to power in Britain, a mature Ewan, given his attitude to ends and means at the end of

Grey Granite

, might have been capable of sending comrades and rivals to their deaths after a show trialâor else of stoically signing his own confession if the Party decided that he was the one to be sacrificed.

It is Ewan's final scene with Ellen that shows the New Man most appallingly in action. Though Ellen is depicted critically

âshe is about to âsell out' to ordinary valuesâyet she was after all the person who helped him through his psychological crisis after police torture, and she is consistently straight and above board in her dealings with others. Ewan rejects her in the most brutal way possible:

But what are you doing out here with me? I can get a prostitute anywhere

⦠He stood looking at her coolly, not angered, called her a filthy name, consideringly, the name a keelie gives to a leering whore; and turned and walked down the hill from her sight.

As Deirdre Burton has put it, âIt is that recourse to the irrelevant insults of sexuality that finally marks Ewan out as the person of limited vision, limited growthâboth personal and political.'

11

Yet, horrified, we empathize with him in his rejection. Writing with hindsight in the years after communism's collapse from within, one is impressed by Gibbon's refusal to endorse Ewan's ethics in this scene, and by the deft impressionism with which he portrays his flawed hero.

Â

Because ideas play such a large part in

A Scots Quair

there has been a tendency for critics to impose an abstract âmeaning' on the trilogy as a whole. What is certain is that, as Edwin Muir put it, Gibbon âwas firmly convinced that man once lived a life of innocence and happiness' in the Golden Age of the Gay Hunters; âbut all his impetuous energy was concentrated on drawing the vital conclusion from this, which was that by breaking the bonds imprisoning him man can live again.' He certainly believed that revolutionary communism was the sword to cut those bonds; but he had also, to continue with Muir's appreciation, âa passionate devotion to such things as truth, justice and freedom, and a belief in their ultimate victory that nothing could shake'.

12

In the beginning he seems to have seen the

Quair

as propaganda for socialist action (âI am a revolutionary writer ⦠all my books are explicit or implicit propaganda', Letter in

Left Review

, February 1935); but the fact surely is that in the white heat of composition it turned into a method of

thinking

about contemporary morals and politics in aesthetic termsâthinking

by means of the images which we call characters. Gibbon's aesthetic thought points to conclusions somewhat different from the sort he was accustomed to formulate in articles or arguments with friends. As Ewan says: