A Sailor's History of the U.S. Navy (12 page)

Read A Sailor's History of the U.S. Navy Online

Authors: Thomas J. Cutler

Even in times of peace, the life of a Sailor can be arduous. While the vast majority of people live and work in places that do not move, Sailors since the earliest days of seafaring eat, sleep, and do their workâwhether it is maintaining weapons, typing reports, or launching aircraftâon decks that move at the whim of wind and sea. They share their quarters with highly explosive substances, dangerous inflammables, and toxic chemicals. Theirs is a world where they perform daily duties on the crest of a storm-driven wave, in the dark and foreboding depths of the ocean, or in the turbulence of a cloud-covered sky. Despite their bond with the sea, many Sailors find themselves in the frigid arctic, a steaming jungle, or a blazing desert.

Many professions have their challenges and difficulties, but it has always taken a unique sort of individual to stand up to the rigors of life in the Navy, whether in surface ships, submarines, aircraft, or the many other branches of the sea service. This is one of the reasons why Sailors can justifiably be proud of the uniform they wear and stand just a little taller when wearing it. They share the knowledge that they come from a long line of tough individuals who, as part of a crew, endured hardships and faced dangers while accomplishing vitally important things for the safety and well-being of their fellow citizens and their nation.

Even though much has changed, much has remained the same in the more than two hundred years that the U.S. Navy has guarded the nation and

projected its power to distant places. Although today's Sailors draw higher pay, have more comforts, and are treated more justly than were their predecessors, they still must contend with many of the same challenges that faced those “Tars” and “Bluejackets” who first took to the sea in the earliest days of the American Revolution. They face many of the same perils and hardships and must still deal with the sadness of leaving loved ones behind as they carry out their duties the world over.

Today's Sailor copes with a very different way of life from the one he or she left behind, one that is rich with tradition of the past yet steaming full speed ahead on the cutting edge of modern technology. Today's Sailor often functions under uncomfortable, taxing conditions, carrying on the necessary tradition of sacrifice that has been one of the hallmarks of the U.S. Navy since its earliest days. It is a tradition shored up by honor, by courage, and not least by commitment, for no one could possibly be a Sailor in the finest sense of the word without being deeply committed to this great nation and its defense.

At the very beginning, the men who chose to go to sea as part of the newly formed American Navy (first called the Continental Navy) were committed to the idea of revolution, to casting off the ties that held them to England in hopes of creating a new nation based upon the rights of man and the principles of life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness.

When John Kilby joined the Navy in July 1779, he joined a tiny force that not only was facing battle with the most powerful navy on earth, but also was one that had to compete for sailors with several other “navies.” All but two of the colonies (New Jersey and Delaware) had formed navies of their own, andâfar worse for the fledgling Continental Navyâthere were countless privateers roaming the seas. It was a common practice of the day for warring nations to encourage private shipowners to capture enemy merchant shipping. If successful, they would share in the profits gained from the sale of the goods carried in the captured vessel.

While this practice was beneficial to the war effort because of the damage it did to the enemy's economy (more than two thousand American privateers took to the sea, seizing British merchant ships and their cargoes and causing insurance rates to skyrocket), it made recruiting for the Continental Navy much more difficult. It took an extra measure of commitment for a young, able-bodied seaman to choose that tiny Navyâwhose mission included facing the warships of the professional and powerful Royal Navyâfor a mere eight dollars a month, when privateers were likely to make more

money while facing less danger. The naval Sailor was far more likely than the privateer to be killed, wounded, or captured.

The Continental Congress offered grants of land to men who would fight as Soldiers in the Army, but no such offer was ever made to those who chose the Navy. So it is no wonder that recruiting for the Navy was challenging in those days. An example of the methods used survives in the record of one of those who, despite his apparent cynicism, signed on.

All means were resorted to which ingenuity could devise to induce men to enlist. A recruiting officer, bearing a flag, and attended by a band of martial music, paraded the streets to excite a thirst for glory and a spirit of military ambition. The recruiting officer possessed the qualifications to make the service appear alluring, especially to the young. . . . When he espied any large boys . . . he would attract their attention by singing in a comical manner:

All you that have bad masters,

And cannot get your due,

Come, come, my brave boys,

And join our ship's crew!

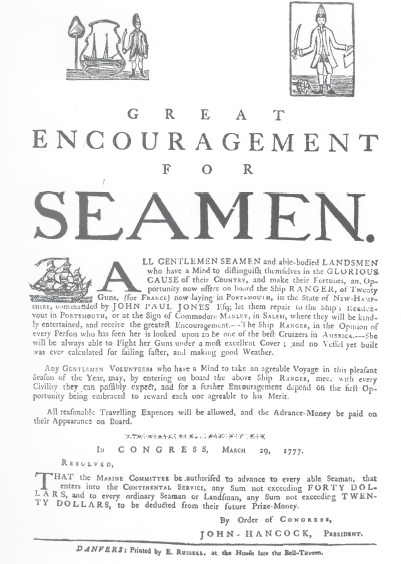

Recruiting posters were plastered on walls along the waterfront of American seaports, offering whatever incentives recruiters could devise. One such poster created in March 1777 used patriotism as its primary incentive, beginning with the heading “Great Encouragement for Seamen”:

ALL GENTLEMEN SEAMEN

and able-bodied

LANDSMEN

who have a Mind to distinguish themselves in the

GLORIOUS CAUSE

of their Country

Yet this same poster did not rely upon love of country alone. The ship seeking the recruits was described in these glowing terms:

The Ship

RANGER

, in the Opinion of every Person who has seen her is looked upon to be one of the best Cruizers in America.âShe will always be able to Fight her Guns under a most excellent Cover; and no Vessel yet built was ever calculated for sailing faster, and making good Weather.

As recruiters have always done, this one painted a slightly “enhanced” description of what the volunteer could look forward to.

ANY GENTLEMEN VOLUNTEERS

who have a Mind to take an agreeable Voyage in this pleasant Season of the Year may, by entering on board the above Ship

RANGER

, meet with every Civility they can possibly expect.

Those who actually signed on might describe this “agreeable voyage” in different terms. Under routine sailing conditions, Sailors like John Kilby could expect to be on watch fully half of their time under wayâbecause the ship was divided into merely two watch sectionsâand the remaining time was allocated to additional work assigned (which was often considerable) and to the necessary functions of sleeping and eating.

The work aboard a sailing ship in those times could be quite dangerous. While the odds were thirteen to one that Kilby would be killed in battle, they were a frightening three to one that he might die in an accident. Indeed, by his own account, Kilby described an incident that occurred shortly after reporting aboard his ship: “The first thing that happened was, as we were beating down to the island of Groix, a man fell off the main topsail yard onto the quarterdeck. As he fell, he struck the cock of [the Captain's] hat, but did no injury [to the Captain]. He was killed and buried on the island of Groix.”

The Kedge Anchor,

a book published some years after the Revolution “as a ready means of introducing Young Sailors to the theory of that art by which they must expect to advance in their profession”âa forerunner to today's

Bluejacket's Manual,

which first appeared in 1902âunderstated the situation when it advised “men perched aloft in a perilous situation will adopt that method which will eventually cost the least time and trouble.” Among the Sailors themselves, it was commonly understood that the rule was “One hand for the ship, one hand for yourself.”

Sails have long since disappeared from the Navy, yet danger has not. Sailors must still climb masts, and although these masts are more user-friendly in many ways, invisible gremlins in the form of volts and amps now lurk there, waiting to do harm to the careless Sailor. There are far fewer lines in the modern warship, yet it takes only one to give way under strain to leave a swath of death and injury in its path. Modern weapon systems are in many ways safer than those cumbersome cannons, yet their explosive power is far more devastating when something goes wrong. Fire, flooding, and falling overboard are the ever-present dangers common to eighteenth- and twenty-first-century Sailors alike. Fuels, electricity, heavy machinery, heights, depths, extremes of temperature, erratic motion, the dark of night, and nature's unpredictable moods are all potentially deadly shipmates to today's Sailor. It takes vigilance and prudence to survive these hazards and serious commitment to meet them head-on in today's Navy.

A Revolutionary War poster used to recruit Sailors for service in the new Continental Navy.

Naval Historical Center

Sleeping was itself a challenge in Kilby's day. Although there were some on boardâknown as “idlers” (cooks, sailmakers, clerks, for instance)âwho stood no watches and therefore could sleep the night through, Kilby and the vast majority of his fellow Sailors could sleep for merely four hours at a time (the two-section watches were “four on, four off”). To make matters worse, they were permitted to sleep only during the hours of darkness, so one night they would get barely four hours of sleep and the next night they might get seven and a half, but with a four-hour watch dead in the middle. Further, a sudden squall or some other emergency could necessitate a call for “all hands” at any time of day, and virtually all the crew (even the idlers) would have to go to their assigned stations to reef topsails or carry out whatever major evolution was needed.

The wristwatch was a long way off, so most on board relied upon the sounding of the ship's bell to know when it was time to go on or off watch. The bell was rung each half hour of the watchâbeginning with one bell on the first half hour, two on the second, and so onâso that by the time a Sailor heard seven bells, he knew he had but half an hour before it was time to relieve the watch.

The Sailor's bed of the day was a hammock, a wonderful place to catch a nap in one's backyard, but not the place to try to sleep night after night. When a Sailor could at last crawl into his hammock, other obstacles to coveted slumber often intervened. The motion of the ship could be quite violent and counter to the swing of the hammock. There was no source of heat or air conditioning, and ventilation was poor at best. Herman Melville, who went to sea in the frigate

United States,

a much larger ship than the earlier one Kilby signed onto, colorfully described sleeping (or trying to) in a sailing man-of-war in his narrative

White-Jacket.

Your hammock is your [prison] and canvas jug; into which, or out of which, it is very hard to get; and where sleep is but a mockery and a name.

Eighteen inches a man is all they allow you; eighteen inches in width; in

that

you must swing. Dreadful! They give you more swing than that at the gallows.

During warm nights in the Tropics, your hammock is as a stew-pan; where you stew and stew, till you can almost hear yourself hiss. . . .

One extremely warm night, during a calm, when it was so hot that only a skeleton could keep cool (from the free current of air through its bones) . . . I lowered myself gently to the deck. Let me see now, thought I, whether my ingenuity cannot devise some method whereby I can have room to breathe and sleep at the same time. I have it. I will lower my hammock underneath all these others; and thenâupon that separate and independent level, at least, I shall have the whole berth deck to myself. Accordingly, I lowered away my pallet to the desired point . . . about three inches from the deckâand crawled into it again. But alas! this arrangement had made such a sweeping semicircle of my hammock, that while my head and feet were at par, the small of my back was settling down indefinitely. I felt as if some gigantic archer had hold of me for a bow.

But there was another plan left. I triced up my hammock with all my strength, so as to bring it wholly

above

the tiers of pallets around me . . . but alas! it was much worse than before. My luckless hammock was stiff and straight as a board; and there I wasâlaid out in it, with my nose against the ceiling, like a dead man's against the lid of his coffin.

When not in use, the hammocks were rolled up and stored in netting triced to the overhead. An early instruction to officers provided guidance for the supervision of this daily ritual: “Nothing adds more to the smart and favorable appearance of a vessel of war than a neat stowage of hammocks. . . . In the stowage of the hammocks, the officer should stand on the opposite side of the deck, a position which will enable him to preserve a symmetrical line, and guide and direct the stower in his progress fore and aft the netting; they are also enjoined to be careful that the hammocks of the men be properly lashed up. Defaulters in this particular should be reported to the First Lieutenant. Seven turns at equal distance is the required number of turns with a hammock-lashing.”