A Rose for the Anzac Boys

Read A Rose for the Anzac Boys Online

Authors: Jackie French

To Private John ‘Jack’ Sullivan, who faced and survived it all; to (Colonel) Dr A.T. Edwards, who did his best to help; to ‘the boys’ of today, and their girls too; and most of all to those indomitable women, the ‘forgotten army’ of World War I, with love, respect and admiration.

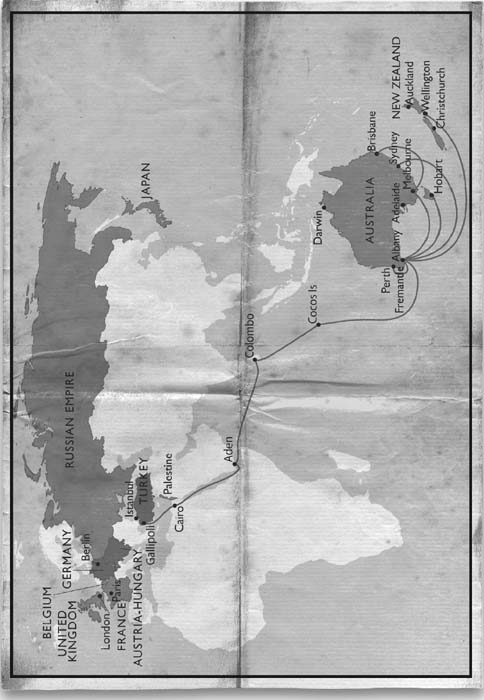

The Route of the first Anzac Troops to WWI

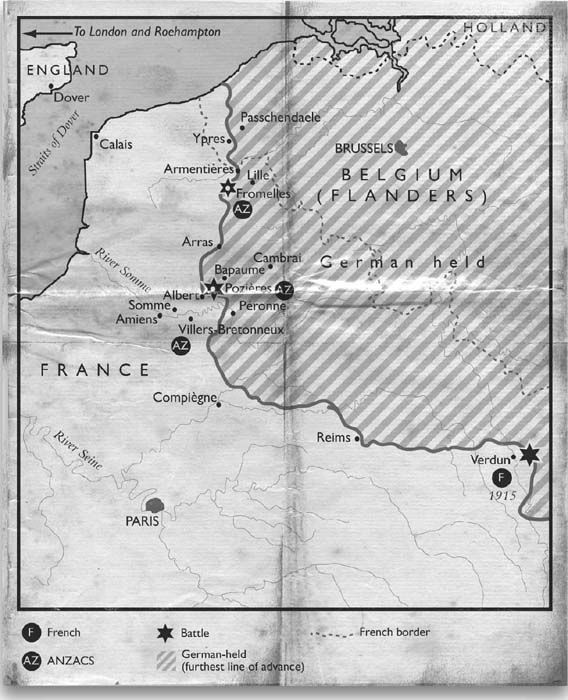

Western Front, France, 1916

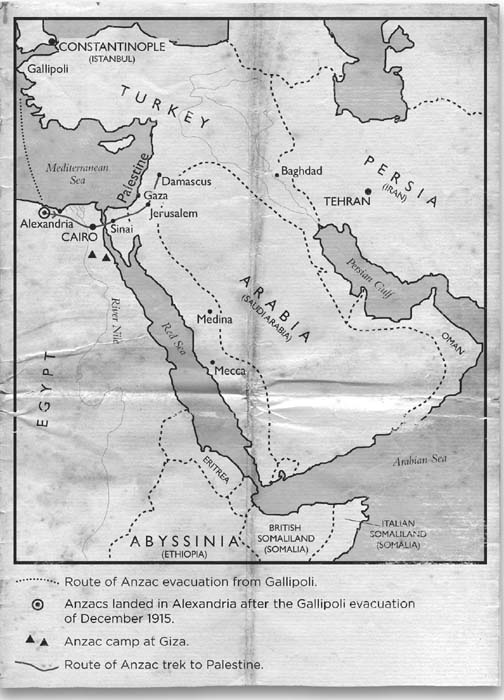

The Middle East during WWI

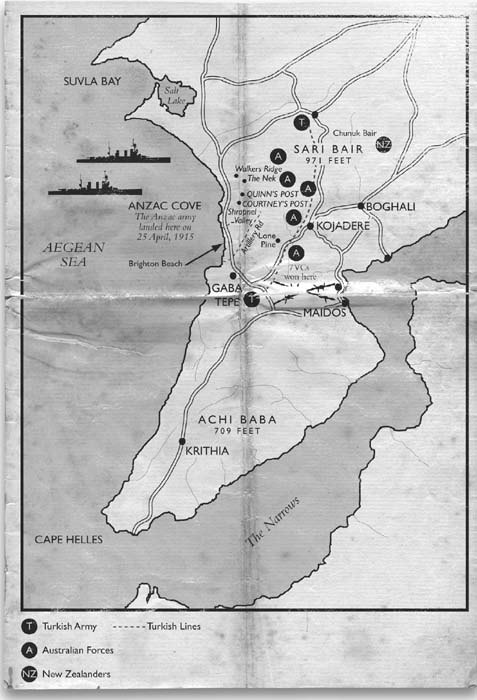

Gallipoli, 1915

BISCUIT CREEK, ANZAC DAY, 1975

At 10 a.m. the street was empty.

The shops showed blank faces to the footpath. Even the Royal Café was shut, though the scent of yesterday’s hamburgers lingered. A kelpie lifted its leg against the butcher’s, then wandered up into the park. It was so quiet you could hear baaing in the distance. Someone must be rounding up sheep on the hill, thought Lachie, as Pa’s ute drew up outside R & G Motors. Dad had been crutching too yesterday. It had been a wet summer. The fly strike was bad.

Lachie slid across the ute’s cracked leather seat and walked round to help Pa out from the driver’s side. You had to tug the driver’s door open, too, and Pa couldn’t manage it alone. Pa refused to buy a new ute. He wouldn’t even drive Dad’s. ‘This one will last me out,’ he’d said,

when Dad tried to argue with him. ‘We’ve grown old together.’

Last year Pa had marched in the Anzac Day parade by himself. That was before he’d fallen down the steps at the doctor’s and broken his hip. Pa could hobble again now. But not up the hill to the war memorial. This year Pa had insisted Lachie push him in a wheelchair. ‘He’s the youngest,’ was all Pa had said. ‘It’s important he remembers.’ As though that explained anything.

It was going to be embarrassing walking up the street in front of everybody, pushing his great-grandfather in a wheelchair. Why couldn’t Grandad do the pushing? Grandad had even been in a war, though he never actually fought because they’d had to take his appendix out, and by the time he was better the war was over. He never marched on Anzac Day.

What if Lachie ran out of puff halfway up the hill? If he had to stop and get his breath back with everybody staring?

Pa looked at his watch. ‘Should be getting here now.’ Pa’s voice was always too loud. It came of being deaf, Dad said.

Lachie handed Pa his walking stick and then lifted the rose out of its jam jar of water. It wasn’t much of a rose. It was pink, with a smudge of white, and its stem was short and floppy, not like the roses from the florist that stood tall and straight. Pa had picked the rose from the tangle that grew along the fence outside the kitchen, and Lachie had held the jar all the way into town, trying not to let the water spill.

Now he handed Pa the rose. ‘The paper said everyone was to meet at ten-thirty.’

Pa ignored the comment. He never argued. He just ignored what people said till they did what he wanted. He peered down the street, the rose drooping in his hand, just as Mum and Dad drove up with the wheelchair they’d borrowed from the hospital.

Lachie ran to help them get it out of the back of the car, mostly so he didn’t have to stay and talk to Pa. He loved Pa, but talking to him was hard now. Pa could only hear these days if you yelled and moved your mouth clearly. Both were embarrassing in public.

Dad pushed the wheelchair up to the ute. Some people looked helpless in wheelchairs, but Pa looked like he was royalty, about to be carried off by his slaves.

That’s me, thought Lachie.

‘Are you sure about this, Pa? It’s a long way for a kid to push,’ Dad said, moving his lips so Pa could lip-read. ‘Bluey would be glad to help out.’

Bluey Monroe was the butcher. He’d served at Tobruk, which was in World War II, the war that Grandad had almost been in, which was different from World War I, where Pa had fought, though the Germans had been the bad guys in both of them.

It was hard to keep the wars straight sometimes, especially with all the other wars since.

Pa ignored Dad, turning away. Pa used his deafness like a weapon. As far as he was concerned, it was settled.

Pa never spoke much at any time. Dad said that came of being deaf too. The war—the

First

World War—had taken Pa’s hearing, though Lachie wasn’t quite sure how. When Pa did speak, he either said no more than was necessary or else he spoke lots, like he’d been saving it up in the cupboard of his mind.

Another car drew up, and another. People appeared in the street now, strolling round corners or heading in from out of town, all making for the war memorial by the park, the men in suits and the women in their not quite Sunday best. The wind whispered up the street, an early breath of winter. Lachie shivered. He wished he’d brought a jumper.

Other ex-soldiers began to gather outside R & G. Three men in uniform, with medals on their chests. A couple of old friends of Pa’s, in suits but with medals pinned to them. A woman in a naval uniform.

Jim Harman slid out of his ute. It was a new blue one with a shiny bull bar. Jim had been in the Vietnam War, which wasn’t long ago, but he didn’t wear his uniform. Other men from Biscuit Creek had gone to Vietnam, but Jim was the only one here today. Jim hadn’t marched before. Pa lifted a hand to him. ‘Glad you made it, son,’ he said.

There was something in Pa’s voice that puzzled Lachie. ‘Glad you made it’—was he just welcoming Jim to the march, or did he mean something more?

The men lined up. There were fifty-six marchers now. Lachie had counted them. Pa was in the front row, which was extra embarrassing because what if Lachie couldn’t keep up with the others as he pushed the wheelchair?

It was all uphill to the memorial. He wished he’d rehearsed it with Pa, tried pushing him uphill last week. But he hadn’t thought of it till now.

Pa held the rose in his hand. It looked even floppier than it had at home.

Mr Hogan from the school began to beat the drum.

Boom. Boom. Boom.

The men began to march, and Lachie pushed.

It wasn’t as bad as he’d thought it would be, at least not at first. Up the main street with dozens of onlookers staring, the men with their hats off, the kids with their bicycles all standing still for these few minutes of respect. Even the dogs stared at the marchers curiously.

Lachie’s arms began to ache.

Boom, boom, boom.

The men’s shoes clumped on the bitumen. Even with the drum and the beat of feet, Lachie had never heard the town so quiet. No one was talking. No one at all.

Boom. Boom. Boom.

Past the post office, the stock and station agency. He was going to make it! It felt good too, with everybody watching. He glanced at the men on either side. Mr Heffernan’s face was expressionless. But Lachie was shocked to see tears in Mr Byrne’s eyes. Mr Byrne had lost three brothers in the war after Pa’s, he remembered. It was funny to think of people missing their brothers even when they were old.

Pa wasn’t crying, was he? Lachie looked down at him in his chair.

Pa’s face, what he could see of it, was…strange. He wasn’t looking at the people in the street. He wasn’t even looking at the others beside him in the parade. It was as though he was watching something far away.

Battles, thought Lachie. He’d seen battles on TV. Was that what Pa was watching? His friends blown to bits, maybe? Did they have guns back in World War I when Pa was young? Or was it swords and bayonet things? Nah, there must have been guns. Pa had a hole in his back from stuff he called shrapnel. He let Lachie put his finger in the scar sometimes.

And then Pa smiled. Lachie saw his cheeks move and bent his head around to see more. It was a soft smile. A smile of love and happiness.

No, thought Lachie, wherever Pa had been it wasn’t in a battle. It was some place good.

They were at the war memorial statue now, the bronze soldier in his uniform with his rifle by his side, and the names of the men who had served and those who had died underneath. Miss Long at school said that the soldier’s uniform was Italian rather than Australian, which was why the Biscuit Creek Committee, who had raised the money, had got the statue cheap. But the soldier looked good at the top of the street, as though guarding the preschool and the dogs sniffing the trees in the park next door.