A-Rod: The Many Lives of Alex Rodriguez (19 page)

Read A-Rod: The Many Lives of Alex Rodriguez Online

Authors: Selena Roberts

Tags: #Non-Fiction, #Biography

“There are all sorts of mechanical devices— like catheters—

athletes use,” says Dr. Gary Wadler, a member of the World AntiDoping Agency. “These methods still go on.”

It would seem a good bit of chicanery was going down for MLB testing that was pitched to players as anonymous. The union tried to calm its players— and their agents— by telling its members that if anyone did test positive, the results would be destroyed. No harm would ever come of it.

Alex was well aware of the upcoming tests and, like many players, made an adjustment in his steroid routine. By 2003, a large number of players were switching from Deca-Durabolin to Primobolan with a low dose of testosterone. Alex was believed to have moved from Deca to Primo during the spring. Quest Diagnostics, which analyzed the tests, was not a sophisticated Olympic-style lab— it’s the kind of place you send your cholesterol tests to, says one antidoping expert— but it did have the capability to detect the obvious.

One of the benefi ts of using Primobolan is that the steroid produces maximum strength with minimum bulk and, even when a player goes off it, there is a long retention of power. “I’ve taken it,” one former player says. “It’s not an Incredible Hulk steroid.”

The drug also has relatively few side effects and, most important, it is detectable for a far shorter period of time than the steroids previously favored by players, Deca-Durabolin and Winstrol. One player trainer puts it bluntly: “Players could piss it out quicker.”

At least 104 players and as many as 115, as federal agents would later discover, either did not fl ush their systems adequately or didn’t even bother, never imagining that their test results would not be destroyed. Apparently, Alex never thought twice. He felt that the union— and thereby, Boras— had his back.

Spring training had one more twist for Alex: in mid-March, he felt stiffness and fatigue in his left shoulder. He hadn’t felt anything

pop or strain, so he tried to play through it, but a CT scan revealed a microscopic tear in the C6–C7 disk. He sat out for two weeks but was ready for the season opener. Alex felt his hefty contract obligated him to play every game, and he had not missed one in two seasons with the Rangers.

There was someone new with the Rangers watching over Al-ex’s workouts: the Rangers new strength and conditioning coach, Fernando Montes, an antisteroid advocate who had worked with the Cleveland Indians for nine years. He knew right away that Alex was a steroid user— and he wasn’t afraid to say so.

Obviously, the Rangers had their suspicions. One day Assistant General Manager Jon Daniels pulled up to Montes in a golf cart.

“Out of the clear blue, he asked, ‘Do you think Alex is juicing?’ ” Montes recalls. “I said, ‘Yes.’ ”

Montes didn’t base his opinion on seeing a needle. He could tell from two decades of experience. “I watched him in the weight room,” Montes says. “He was complaining about work level and intensity. What he was doing didn’t match up to the numbers he was putting up and his ability to recover 162 games playing the way he does.”

He also noticed how removed Alex was from the other Rangers. Alex was known to shower separately in an effort to hide steroid side effects from teammates. “You see it with steroid users: they act like they have a secret,” Montes says. “They only talk to certain people inside and outside the clubhouse. They withdraw.”

Buck Showalter tried to clear the Rangers’ workplace of pals and posses. Showalter had seen Presinal— and didn’t know much about him— but he didn’t want player fl ies buzzing around. At one point, Showalter, hoping to declutter Alex’s baseball world, suggested he pare down his entourage. Alex listened, but nothing changed.

There were fewer and fewer people in Alex’s life who tried to bend his will— even a little. Eddie Rodriguez (no relation) had

THE GREATEST*

“I haven’t seen too many guys who can get their bat through the hitting zone any faster than Alex,” said Rodriguez’s first professional hitting coach, Lee Elia, of the Seattle Mariners. “With his ability, there’s no telling what he can accomplish.” RONALD MARTINEZ/GETTY

IMAGES

IS BRO

/CNAM

RGE B

IDV

DA

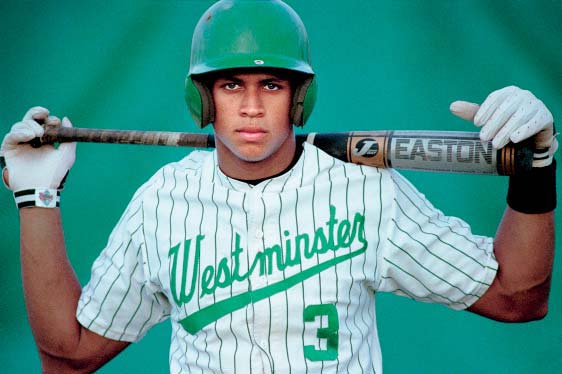

Rodriguez hit .505 with 9

home runs and 35 stolen

bases during his senior

year at Miami’s Westminster High. In 1994 he

was the first draft pick

overall for the Seattle

Mariners. BILL FR AKES—

SPORTS ILLUSTR ATED/GETTY

JUNIOR MINTED

Batting in front of Ken Griffey Jr. ensured that Rodriguez saw a lot of fat pitches in the strike zone as a rookie. In 1996, his first full season with the Mariners, he led the majors with a .358 batting average while hitting 36 home runs and 123 RBIs. As Rodriguez’s star rose, Junior got jealous: “One day, I’d like to hit in front of me, too.” OTTO GREULE JR./ALLSPORT/GETTY

Y TTE

/GTROPSLL

/AREBRA BYR

GA

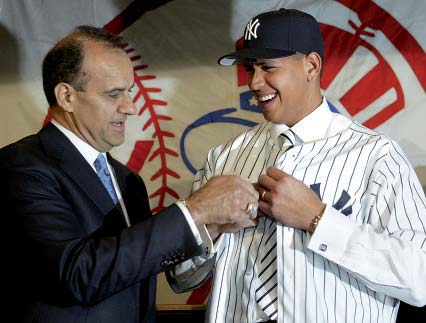

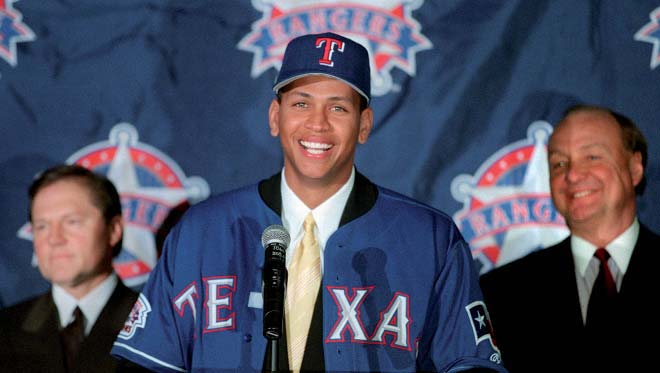

MR. TWO-FIFTY-TWO

Rodriguez, with agent Scott Boras

(left)

and Texas Rangers owner Tom Hicks, is introduced as a Ranger after signing his record-breaking, 10-year, $252 million contract in 2001. The Rangers were awful, but in 2003

Rodriguez was named the American League MVP. He later admitted to using the steroid Primobolan for the three seasons he played in Texas.

GREG FIUME/NEWSPORT/CORBIS

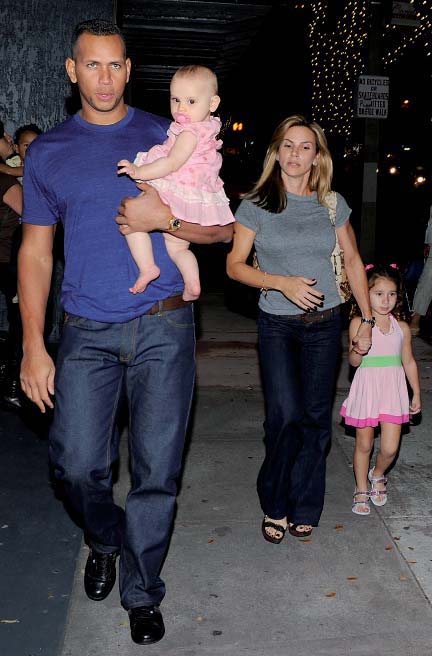

INTRODUCING C-ROD

Rodriguez met Cynthia

Scurtis at a Miami gym in

1996. Over the objections of her family, they dated for six years before marrying in 2002

at the home of Rangers owner Tom Hicks. The couple, who have two children, divorced in 2008. KEVIN MAZUR/NFL FOR

BRAGMAN NYMAN CAFARELLI/GETTY

Y T

ET

/GEGAMEI

IR

/WNODR

IS GO

CHR