A People's Tragedy (81 page)

Read A People's Tragedy Online

Authors: Orlando Figes

46 Cossacks patrol the streets of Petrograd, early February 1917. Recruited from the poorest regions of the Kuban and the Don, they soon joined the revolutionary crowds.

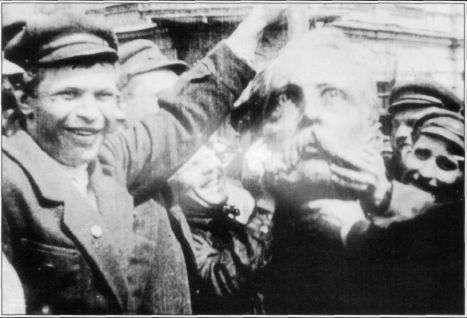

47 A 'pharaon' - the slang name for a policeman - is arrested by a group of soldiers during the February Days in Petrograd.

48-9 The destruction of tsarist symbols.

Above:

a group of Moscow workers playing with the stone head of Alexander II in front of a movie camera.

Below,

a crowd on the Nevsky Prospekt in Petrograd stand around a bonfire with torn-down tsarist emblems during the February Days. Here, too, the display for the camera was an important part of the event.

50 The crowd outside the Tauride Palace, 27 February 1917.

51 Soldiers on the Western Front receive the announcement of the abdication of Nicholas II.

second stage of the revolution': no support for the Provisional Government; a clean break with the Mensheviks and the Second International; the arming of the workers; the foundation of Soviet power (the 'democratic dictatorship of the proletariat and the poorest peasants'); and the conclusion of an immediate peace. Lenin boiled all this down into ten punchy theses — his famous April Theses — during the train journey from Switzerland and began to agitate for them upon his arrival at the Finland Station.

Brushing aside the formal welcome of the Soviet leaders, the returning exile proclaimed the start of a 'worldwide Socialist revolution!', and then went out into the square, where he climbed on to the bonnet of a car and gave a speech to the waiting crowd. Above all the noise Sukhanov heard only the occasional phrase: '. . . any part in the shameful imperialist slaughter . .. lies and frauds . . . capitalist pirates . . .' Lenin was then taken off in an armoured car, which proceeded with a military band, workers and soldiers waving red flags, through the Vyborg streets to the Bolshevik headquarters — the palace of Kshesinskaya, the former ballerina and sometime mistress of the Tsar.52

On the following day Lenin came with his own armed escort to the Tauride Palace and presented his Theses to a stunned assembly of the Social Democrats. He had turned the Party Programme on its head. Instead of accepting the need for a 'bourgeois stage' of the revolution, as all the Mensheviks and most of the Bolsheviks did, Lenin was calling for a new revolution to transfer power to 'the proletariat and the poorest peasants'. In the present revolutionary conditions, he argued, a parliamentary democracy would be a

'retrograde step' compared with the power of the Soviets, the direct self-rule of the proletariat. Theoretically, the April Theses had their roots in the lessons which Lenin had learned from the failure of the 1905 Revolution: that the Russian bourgeoisie was too feeble on its own to carry out a democratic revolution; and that this would have to be completed by the proletariat instead. The Theses also had their roots in the war, which had led him to conclude that, since the whole of Europe was on the brink of a socialist revolution, the Russian Revolution did not have to confine itself to bourgeois democratic objectives.* But the practical implications of the Theses — that the Bolsheviks should cease to support the February Revolution and should move towards the establishment of the Dictatorship of the Proletariat — went far beyond anything that all but the most extreme left-wingers in the party had ever considered before. It was still not clear whether Lenin envisaged the violent overthrow of the Provisional Government, and, if so, when this should happen. For the moment, he seemed content to limit the party's tasks to mass agitation. The Bolsheviks still lacked a majority

* Trotsky had reached the same conclusions, and it is possible that his theory of the

'permanent revolution' partly influenced the April Theses.

in the Soviets; and Russia, as Lenin pointed out, was

'now

the freest of all the belligerent countries in the world'. But the sheer audacity of his speech, coming as it did at a joint SD assembly for the party's reunification, ensured a furious uproar in the hall.

The Mensheviks booed and whistled. Tsereteli accused Lenin of ignoring the lessons of Marx and quoted Engels on the dangers of a premature seizure of power. Goldenberg said that the Bolshevik leader had abandoned Marxism altogether so as to occupy the anarchist throne vacated by Bakunin. B. O. Bogdanov condemned the Theses as 'the ravings of a madman'. Even Semen Kanatchikov, the Bolshevik worker we met in Chapter 3, who had come all the way from the Urals to hear Lenin speak, was flabbergasted by what he saw as the 'unrealistic nature of his ideas, which seemed to all of us to go far beyond the realms of what it was possible to achieve'. It seemed that Lenin, having spent so many years in exile abroad, had become out of touch with the realities of political life in Russia. Returning from the Tauride Palace that evening, Skobelev, the Menshevik, assured Prince Lvov: 'Lenin is a has-been.'53

Which is just what he might have become, had it not been for one fact: that he was Lenin. All the odds were stacked against him in his struggle for the party to adopt the April Theses. The majority of the Bolsheviks had already pledged their tentative support for the Provisional Government prior to Lenin's arrival (Kollontai was the only major Bolshevik to support the April Theses from the start). Only the Vyborg Committee, the stronghold of Bolshevik extremism in the capital, came out in favour of Soviet power.

Stalin and Kamenev, who returned from Siberian exile in mid-March and took over control of

Pravda,

strengthened this cautious approach. Like the Mensheviks, they assumed that the 'bourgeois' stage of the revolution still had a long way to run, that the dual power system was thus necessitated by objective conditions, and that the immediate tasks of the Bolsheviks lay in constructive work within the social democratic movement as a whole. Trotsky later accused them of acting more like a loyal opposition than the representatives of a workers' revolutionary party. The moderate motions of Kamenev and Stalin were adopted at the All-Russian Bolshevik Conference at the end of March: conditional support for the Provisional Government; the continuation of the war; support for the Soviet leaders. The Bolsheviks even agreed to explore the possibilities of reuniting with the Mensheviks. They were already working together, along with the SRs and other socialists, in most of the provincial Soviets. Far away from the factional disputes of their party leaders in the capital, the old camaraderie of the underground remained very strong in the provinces, and Lenin's combative factionalism was strongly resented and resisted by those provincial Bolsheviks who were either unwilling or simply unable to break their ties with the other left-wing groups.54

Lenin always liked a fight. It was as if the whole of his life had been a preparation for the struggle that awaited him in 1917. 'That is my life!' he had confessed to Inessa Armand in 1916. 'One fighting campaign after another.' The campaign against the Populists, the campaign against the Economists, the campaign for the organization of the party along centralist lines, the campaign for the boycott of the Duma, the campaign against the Menshevik liquidators', the campaign against Bogdanov and Mach, the campaign against the war — these had been the defining moments of his life, and much of his personality had been invested in these political battles. As a private man there was nothing much to Lenin: he gave himself entirely to politics. There was no 'private Lenin' behind the politician. All biographies of the Bolshevik leader become unavoidably discussions of his political ideas and influence.

Lenin's personal life was extraordinarily dull. He dressed and lived like a middle-aged provincial clerk, with precisely fixed hours for meals, sleep, work and leisure. He liked everything to be neat and orderly. He was punctilious about his financial accounts, noting on slips of paper everything he spent on food, on train fares, on stationery, and so on. Every morning he tidied his desk. His books were ordered alphabetically. He sewed buttons on to his pin-striped suit, removed stains from it with petrol and kept his bicycle surgically clean.55

There was a strong puritanical streak in Lenin's character which later manifested itself in the political culture of his regime. Asceticism was a common trait of the revolutionaries of Lenin's generation. They were all inspired by the self-denying revolutionary hero Rakhmetev in Chernyshevksy's novel

What Is To Be Done?

By suppressing his own sentiments, by denying himself the pleasures of life, Lenin tried to strengthen his resolve and to make himself, like Rakhmetev, insensitive to the suffering of others. This, he believed, was the 'hardness' required by every successful revolutionary: the ability to spill blood for political ends. 'The terrible thing in Lenin', Struve once remarked, 'was that combination in one person of self-castigation, which is the essence of all real asceticism, with the castigation of other people as expressed in abstract social hatred and cold political cruelty.' Even as the leader of the Soviet state Lenin lived the spartan lifestyle of the revolutionary underground. Until March 1918 he and Krupskaya occupied a barely furnished room in the Smolny Institute, a former girls'

boarding school, sleeping on two narrow camp-beds and washing themselves with cold water from a bowl. It was more like a prison cell than the suite of the dictator of the biggest country in the world. When the government moved to Moscow they lived with Lenin's sister in a modest three-room apartment within the Kremlin and took their meals in the cafeteria. Like Rakhmetev, Lenin did weight training to build up his muscles. It was all part of the macho culture (the black leather jackets, the militant rhetoric, the belief in action and the cult of violence) that was the essence of Bolshevism. Lenin did not smoke, he did not really drink, and, apart from his romantic friendship with Inessa Armand, he was not interested in beautiful women. Krupskaya called him 'Ilich', his popular name in the party, and he called her 'comrade'. She was more like Lenin's personal secretary than his wife, and it was probably not bad luck that their marriage was childless. Lenin had no place for sentiment in his life. 'I can't listen to music too often,' he once admitted after a performance of Beethoven's Appassionata Sonata. 'It makes me want to say kind, stupid things, and pat the heads of people. But now you have to beat them on the head, beat them without mercy.'56