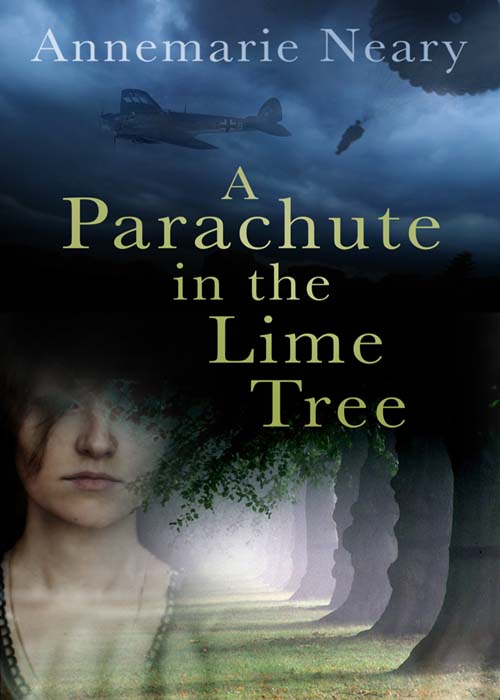

A Parachute in the Lime Tree

Read A Parachute in the Lime Tree Online

Authors: Annemarie Neary

For my son Rory

Hedy Lamarr and the Parachute Man

The Fall

Oskar had never been afraid of falling. He’d always loved the abandonment of the jump and the feeling of reprieve when the parachute did its job. This time, though, he screamed his way down. Once the parachute jolted in, he was a puppet in the dark.

He didn’t see the tree. It tossed him this way and that as he bumped down through its layers. He felt a sharp twist to his knee, and was stationary at last, slung upside down among the branches. Then the rain began, coming at him from all angles and pelting the earth beyond the tree. He released his harness: tugged at the ropes, swung on them. The canopy of the tree released a shower of raindrops but the parachute wouldn’t shift. The moon slid out from behind the clouds like a searchlight, and made it stubbornly visible.

He’d dreaded the jump but he was through the hatch before the others had time to tackle him. Willy was the only one who was quick enough but he couldn’t hold his grip. As he plunged free of the plane, and the cold air whistled in his ears, Oskar was suddenly unreachable. Now, though, the parachute flapping overhead seemed like a bad omen.

It was only when he’d clambered painfully down that he saw the house. His first instinct was to head off in the opposite direction, until he realised the overgrown garden gave the only shelter for miles. Here and there, a small tree clawed at the lightening sky but there were no woods, no natural hiding places at all.

He skirted the right flank of the house, limped his way past an old bathtub invaded by weeds and scrawny daffodils, and headed for the densest growth. He was desperate to find somewhere to stop, think, gather himself. He pissed into a clump of nettles,

and a cat sped out from under a bush and scrambled onto a wall, eyeing him suspiciously. Down here, there were traces of an old vegetable patch and a rotting shed that was barely distinguishable from the growth around it. Inside, it smelt of damp earth and rot, and the only window was green with slime. It might have been a summerhouse, though he doubted it had ever seen much sun. When he lifted a cushion, a trail of small black mice squealed out the door. There were jars of dark viscous liquids, a jumble of brushes and pencils in an old tin can; scraps of faded diagrams were pinned to the window frame.

He could hardly remember the last time he’d been alone. Before Vannes, there was the training school at Köthen: before that, the endless hikes with the Hitler Jugend. There had always been someone to tell him what to do next. Now, he didn’t even know where exactly he was.

Later, when the sky was bright, there were voices and the scrape of something along a path but soon the sounds faded again. By now his knee had swollen; he forced himself to stand on it and used an old rag that smelt of linseed to bind it up but it wouldn’t take him far. He fell into a fitful sleep. Joachim was there, playing his clarinet in some late-night bar with three elderly women in

dirndl

; there was the Jew with the bloodied face on the ground outside the Cafe Weissner, and Reinhard in his black uniform, drinking plundered French cognac with Vati. Elsa hardly featured but that’s the way with dreams.

He awoke to the sound of an engine, and unsheathed his knife. After a while, he heard the vehicle drive off again. He remained on his guard, though, certain that by now someone would have seen the parachute. Hours passed and no one came, and fear turned to boredom. He found a tin of boiled sweets on the shelf, crunched on them two at a time, pooling the saliva in his mouth to try and quench his thirst. Afterwards, his mouth tasted of metal and he was thirstier than ever.

By nightfall, his tongue was dry against the roof of his mouth and his whole body felt battered. He opened the door of the shed just wide enough, then hobbled his way to the edge of the undergrowth. In front of the house was a grassy area, more field than lawn, then a gravelled stretch. Overhead, there was an ocean of stars so vast it took his breath away. He had forgotten a sky could be so silent. Once, with Elsa, back in Berlin in the old days, they had each chosen a star. Elsa wasn’t interested in spring skies and winter skies and all the technical stuff.

‘I’ll just take the one above my head, Oskar. What does it matter which star is mine? A star is a star.’

But it mattered. And when the night sorties began, he became superstitious about catching sight of it. He would crouch in the gondola beneath the black belly of the plane like a grub in a cocoon, sickened by the smell of fuel, legs frozen, certain he’d be the one to catch the first hit. As he flew through clear, star-scattered skies to light the targets for the bombers who would follow, he always kept his eyes down.

He watched the house for signs of life. A dim light burned in a downstairs window. When the light died, he waited. Then, he took off his boots to cross the gravelled path that separated the house from the garden and crept in through an unlocked door. He drank in splutters from the tap, filled his can with water. In the pantry, he tore a hunk off a rough loaf, found some hard cheese under a china dome. He cracked an egg into a cup, then, holding his nose, he gulped it down. The clanging of a clock startled him. The sound was identical to his own family’s hall clock, the one his father had threatened to throw in the Spree, and for an instant he was back home in Zweibrückenstrasse with his sister, Emmi.

‘Forget her, Oskar. She’s not coming back.’

They struggled through a blizzard for most of the way but it was in the wilds of Brandenburg that the snow finally forced the train to a halt. For a while it looked as though Oskar’s leave would be spent out there in the wilderness, but in the end they sent a snowplough out to clear the tracks and the train made it to Berlin after all. By the time he reached Zweibrückenstrasse, he was exhausted. As he walked up the path, he turned his head away from the Frankels’ house, determined to start things on a positive note. Inside, with the

Eintopf

on the hob and the log fire burning, he felt reassured; it still smelt like home. His mother kissed him gingerly; his father clapped him on the back. When he asked where Emmi was, Vati seemed taken aback, as if it wasn’t an obvious question.

‘Married,’ Mutti glanced at him nervously, ‘to Reinhard. How long ago, Gert?’

‘Oh, it must be a month or so.’

They used to joke about Reinhard, always strutting about with those friends of his. Oskar was barely in the door but already he felt the house close in on him. ‘Nobody wrote. Why didn’t Emmi–’

‘Let’s get you something to drink, Oskar. Some hot milk with cinnamon, maybe, something to warm you up,’ said Vati.

‘There was no church ceremony, nothing like that.’ Mutti was brushing invisible crumbs from the lap of her skirt. ‘It was just a Party affair. We weren’t even there ourselves, darling.’ When he opened his mouth to speak, she cut in, ‘Emmi made her own bed.’

It was too soon for a row. Oskar went upstairs to change, even though there was no need. Mutti had kept all his old uniforms,

right back to Hitler Jugend days, and they hung in size order in the closet, each lie bigger than the next. He turned his back on them, and went over to the window. It looked like the Frankels’ garden had been cleared, and lights shone out onto the snow from a downstairs room. For a moment it was as though none of it had happened at all. He raced down the stairs and almost knocked into Vati, who was crossing the hallway with a tray of drinks.

‘When did they get back?’

‘Nobody came back. We have new neighbours now.’ Vati raised his tray a little, but Oskar shook his head and made for the door without even bothering with a jacket. The Frankels’ house looked freshly painted and the torn curtain was gone. The snow had stopped, and now that he was outside he felt his head begin to clear. He couldn’t bring himself to go back in, so he just kept on walking. People passed in flurries, the phosphorous buttons on their outer clothing darting about like fireflies. He didn’t go anywhere in particular, just walked around in circles, clapping his arms to keep the blood moving. It was hard to believe the war was happening at all; there was so little sign of it here. So far, the English had only managed a graze or two and the city remained confident, out of reach.

Next morning, no one mentioned his disappearance the night before.

‘I’ve saved the

Eintopf

,’ Mutti said. ‘We won’t bother with a big party. Just Frau Auger, of course, and Sophie.’

Oskar wondered what made Frau Auger such essential company; he wasn’t even sure he could place her. He’d no idea who Sophie was.

‘Oh Oskar, you remember: Emmi’s friend, from the choir. Emmi had such high hopes for you two.’

When he saw Frau Auger, he recognised her right away. She was one of the women Elsa had been fearful of; some incident

he couldn’t recall now involving Herr Goldmann. As he sat down opposite her, he noted the little blue and white motherhood bow pinned to her lapel. He was surprised Mutti had any time for the likes of Frau Auger. ‘I’m as much in favour of a glorious Fatherland as the next woman,’ she used to say, ‘but is there any need to be so unpleasant about it?’

Sophie spoke incessantly about a boyfriend who had some cushy number doing research flights with Telefunken. Frau Auger didn’t say much but Oskar felt her dissect him like the meat on her plate. Once he’d had a glass or two of wine, he decided to take her on. ‘I see they gave someone the Frankels’ house,’ he said. ‘When did that happen?’

‘Oh, Oskar, dear,’ Mutti fumbled. ‘It’s hard to put a date on these things. People are always coming and going. Late summer? Not long after you left, I suppose.’ She turned to Frau Auger, ‘You know, the berries this year really were the best in years. We’ve had so many jams and jellies and compotes.’

Frau Auger chewed slowly, glancing up at Oskar from time to time.

‘Where are the Frankels’ things?’ he asked.

‘Long gone,’ Frau Auger said. ‘Sold or dumped.’ She tilted her head to one side, awaiting his reaction.

‘Stolen?’

‘Confiscated.’

‘Oskar, why don’t you tell us about Brittany, darling. Is it as beautiful as they say? And does it rain all the time?’ Mutti knocked over a glass of white wine with her elbow and began dabbing at it with her handkerchief. She looked like she might cry. Frau Auger crossed her knife and fork, and straightened herself in her chair.

‘Go on,’ she told Oskar, as she patted Mutti’s hand maternally.

When Oskar looked up from the mesmerising whiteness of the dinner plate, all four faces were fixed on him. ‘There is no point,’ he murmured finally.

Frau Auger gave a small smile. ‘Precisely,’ she said. ‘What’s gone is gone.’

By the time Oskar got up the next morning, the house was empty. He walked through each floor, trawling it for some tiny sign of change. But even Emmi’s room was exactly as it had always been, with her pink eiderdown folded neatly down and her collection of carved animals still on her dressing table. On the attic landing, a jag of sunlight blinded him a moment as he turned to mount the final flight of stairs.

Mutti’s attic was a place of crates and packing cases and infallible order. It was a source of pride to her that she could put her hand on anything at all. Items were stored according to the frequency of their use, so that the Christmas decorations, used annually, were kept nearer the door than the schoolbooks that would probably never be read again. When he opened the door, he was astonished to find the place in chaos. There were papers strewn all over the floor, a string of glass beads, a fur collar, a jumble of scarves. Most of the paper seemed to belong to an academic dissertation of some sort, but there were other things, too: bills and general correspondence, even a handwritten score. He knelt down in the middle of it all and began to read.