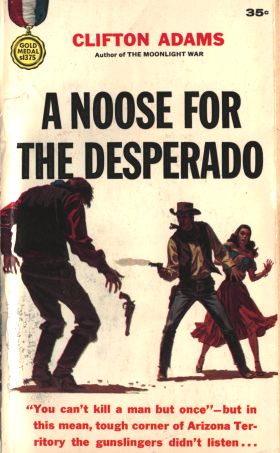

A Noose for the Desperado

Clifton Adams

Copyright 1951 by Clifton Adams

He came forward slowly, in that curious toe-heel gait that Indians

have. With a big left hand, he grabbed Marta by the hair and jerked her

half out of the chair.

I hit him in the face and pulled Marta behind me.

“Keep your damn hands off her if you want to go on living,” I said.

He was surprised. The next thing I knew his gun was coming out of the

holster.

I made my grab and didn't bother to aim.

I didn't hit him. I didn't even come close.

But I didn't need that first bullet. Just the muzzle blast.

And the Indian knew it. His mouth flew open as he slammed back under

the impact, and before he could swing that pistol on me again, he was

as good as dead.

I SCOUTED THE TOWN for two full days before going into it. There

hadn't been any sign of cavalry, and I figured the law wouldn't be much

because nobody cared what happened to a few Mexicans. There it stood

near the foothills of the Huachucas, a few shabby adobe huts and one or

two frame buildings broiling in the Arizona sun. But to me it looked

like Abilene, Dodge, and Ellsworth all rolled into one.

It had been a long trail from Texas, and my horse was sore-footed and

needed rest and a bellyful of grain. I was beginning to grow a fuzzy

beard around my chin and upper lip, and I had a second hide of trail

dust that was beginning to crawl with the hundred different kinds of

lice that you pick up in the desert. I was ready to take my chances on

somebody recognizing me, just so I could get a bath and a shave and

maybe a change of clothes.

So that was how I came to ride into this little place of Ocotillo, on

that big black horse that used to belong to my pal Pappy Garret. I had

Pappy's rifle in the saddle boot and Pappy's guns tied down on my

thighs. But that was all right. Pappy didn't have any use for them. The

last time I saw him had been on a lonely hilltop in Texas. He had died

the way most men like that die sooner or later, I guess, with a

lawman's bullet in his guts.

It was around sundown when we hit this place of Ocotillo, and it

turned out that it was on the fiesta of San Juan's Day. I didn't know

that at the time, but it was clear that they were having a celebration

of some kind. The men were all in various stages of drunkenness, some

of them singing and pounding on heavy guitars. Some of the young bucks

were dancing with their girls in the dusty street or in the cantinas. A

fat old priest was grinning at everybody, and the kids were crying and

shouting and singing and rattling brightly painted gourds. It was

fiesta, all right. It was like riding out of death into life.

I pulled my horse up at a watering trough and let him drink while the

commotion went on all around us. Three girls in bright dresses danced

around us, giggling. The big black lifted his nose out of the trough

and spewed water all over them and they ran down the street screaming

and laughing. Everybody seemed to be having a hell of a time.

Another girl came up and slapped the black's neck, looking at me.

“Hello, gringo!” she said.

“Hello, yourself.”

“You come to fiesta, eh?” she said. Then she laughed and slapped the

black again.

“Is that what it is, fiesta?”

“Sure, it's fiesta. San Juan's Day.” She laughed again. “Where you

come from, gringo? Long way, maybe. You plenty dirty.”

“Maybe,” I said. “Can I find anybody sober enough to give me a shave

and fix a bath?”

“Sure, gringo,” she grinned. “You come with me.”

I had been looking around, not paying much attention to the girl. But

now I looked at her. She was young, about eighteen or nineteen, but she

wasn't any kid. Her dark eyes were full of hell, and when she flashed

her white teeth in a grin you got the idea that she would like to sink

them into your throat. She wore the usual loud skirt and fancy blouse

with a lot of needlework on it that Mexicans like to deck themselves

out in on their holidays.

“Look!” she yelled. Then she started jumping up and down and laughing

like a kid.

Somebody had turned an old mossy-horn loose in the street and

everybody was scattering and screaming as if a stampede was bearing

down on them. The old range cow shook its head, bewildered; then some

kids came up and began prodding it down the street. The yelling and

screaming kept up until the cow disappeared down at the other end. That

seemed to be a signal for everybody to have another drink, so all the

menfolks started crowding into the cantinas.

“Does that end the fiesta?” I asked.

“Just beginning,” she said. “At night they go to church and burn

candles and pray to San Juan that their souls may be saved.” She

laughed again. “Then they drink some more. Tomorrow they go back to the

fields and work until next San Juan's Day.”

“How about that bath and shave?” I said.

“Sure, gringo. Come with me.”

I left my horse at the hitching rack, but I took the rifle out of the

saddle boot. The girl led me between two adobe huts, then through a

gate in a high adobe wall. The wall completely surrounded a little plot

at the back of the hut. A dog slept and some chickens scratched under a

blackjack tree.

“This is a hell of a place for a barbershop,” I said.

“No barber,” the girl grinned. “I shave.” She cut the air with her

hand, as if slicing someone's throat with a razor.

“No, thanks,” I said.

She laughed. “No worry, gringo. I fix.”

She took my arm and led me into the house. The thick adobe walls made

the room cool, and there was a pleasant smell of wine and garlic. It

was like walking into another world. There was nothing there to remind

me of the fiesta, or of the lonesome desert, or Pappy Garret. In this

house I could even forget myself. I felt a little ridiculous wearing

two pistols and carrying a rifle.

“Whose house is this?” I said.

She stabbed herself with a finger. “My house.” Then she yelled,

“Papacito!”

When she got no answer, she shrugged. “Come with me.”

The house had only two rooms. The first room had a fireplace and a

charcoal brazier for cooking and a plank table and three leather-bottom

chairs. In one corner there were some blankets rolled up, and I figured

that was where Papacito slept when he was home. The other room had a

mound of clay shaped up against one wall with some blankets on it, and

that was the bed. A rough plank wardrobe and another leather-bottom

chair completed the furniture.

“Wait here,” the girl said.

She went out and I heard her shaking up the coals in the fireplace,

and pretty soon she came back lugging a big wooden tub. “For bath,” she

said. On the next trip she brought a razor and a small piece of yellow

lye soap. “For shave.”

I grinned. “I can't complain about the service.”

“You wait,” she said.

I was too tired to try to understand why she was going to so much

trouble. Maybe that's the way Mexicans were. Maybe they liked to wait

on the gringos. I was beginning to feel easy and comfortable for the

first time since I had left Texas. I pulled off my boots, sat in the

chair, and put my feet on the clay bed. I was beginning to like Arizona

just fine.

“Say,” I called, “have you got anything to drink?”

She came in with a crock jug and handed it to me. “Wine,” she said.

I swigged from the neck and the stuff was sweet and warm as it hit my

stomach. “Thanks,” I said. Then I had another go at the jug, and that

was enough. I never took more than two drinks of anything.

That was partly Pappy Garret's teaching, but mostly it came from

seeing foothills filled with gunmen who could shoot like forked

lightning when they were sober, but when they forgot to set the bottle

down they were just another notch in some ambitious punk's gun butt.

The girl came in with a crock bowl of hot water. I got up and she put

the water on the chair and a broken mirror on the wardrobe.

“Bath before long,” she said, and went back into the other room.

She had a way of knocking out all the words except the most essential

ones, but she spoke pretty good English.

I went over to the wardrobe and inspected my face in the mirror. It

gave me quite a shock at first, partly because I hadn't seen my face in

quite a while, and partly because of the dirt and beard and the sunken

places around the cheeks and eyes. It didn't look like my face at all.

It didn't look like the face of a kid who still wasn't quite twenty

years old. The eyes had something to do with it, and the tightness

around the mouth. I studied those eyes carefully because they reminded

me of some other eyes I had seen, but I couldn't place them at first.

They had a quick look about them, even when they weren't moving. They

didn't seem to focus completely on anything.

Then I remembered one time when I was just a sprout in Texas. I had

been hunting and the dogs had jumped a wolf near the arroyo on our

place, and after a long chase they had cornered him in the bend of a

dry wash. As I came up to where the dogs were barking I could see the

wolf snarling and snapping at them, but all the time those eyes of his

were casting around to find a way to get out of there.

And he did get out, finally. He was a big gray lobo, as vicious as

they come. He ripped the throat of one of my dogs and blasted his way

out and disappeared down the arroyo. But I heard later that another

pack of dogs caught him and killed him.

“What's wrong?”

The girl came in with a kettle of hot water and poured it into the

tub.

“Nothing,” I said, and began lathering my face.

I started to leave my mustache on, thinking that it might keep people

from recognizing me, but when I got the rest of my face shaved my upper

lip looked like hell. It was just some scraggly pink fuzz and I

couldn't fool anybody with that. The girl poured some cold water in the

tub on top of the hot, and filled it about halfway to the top.

“Ready,” she said. “Give me clothes.”

“Nothing doing. I take a bath in private or I don't take one at all.”

“To wash,” she added.

These Mexicans must be crazy, I thought. Why anybody would want to

take a saddle tramp in and take care of him I didn't know. But it was

all right with me, if that was the way she wanted it.

“All right,” I said. “You get in the other room and I'll throw them

through the door.”

She stood with her hands on her hips, grinning. “Gringos!” But she

went in the other room and I began to strip off. When I threw the

things in the other room she picked them up and went outside.

I must have soaked for an hour or more there in the tub, twisting and

turning and scrubbing every inch of myself that I could reach. It was

dark outside, and the only light in the house came from the fireplace

in the other room.

“Say,” I called, “are those clothes dry yet?”

“Pretty soon,” she said. Her voice was so close it made me jump.

Instinctively, I made a grab for my pistols, which I had put on the

chair and pulled up beside the tub, but she laughed and I stopped the

grab in mid-air.

“Get the hell out of here,” I said.

She was leaning against the wardrobe laughing at me, and with the red

light from the fireplace playing on her face. She must have found my

tobacco and corn-shuck papers in my shirt, because there was a thin

brown cigarette dangling from one corner of her mouth. That shook me,

because I had never seen a woman smoke before, except for the fancy

girls in Abilene or Dodge or one of the other trail towns.