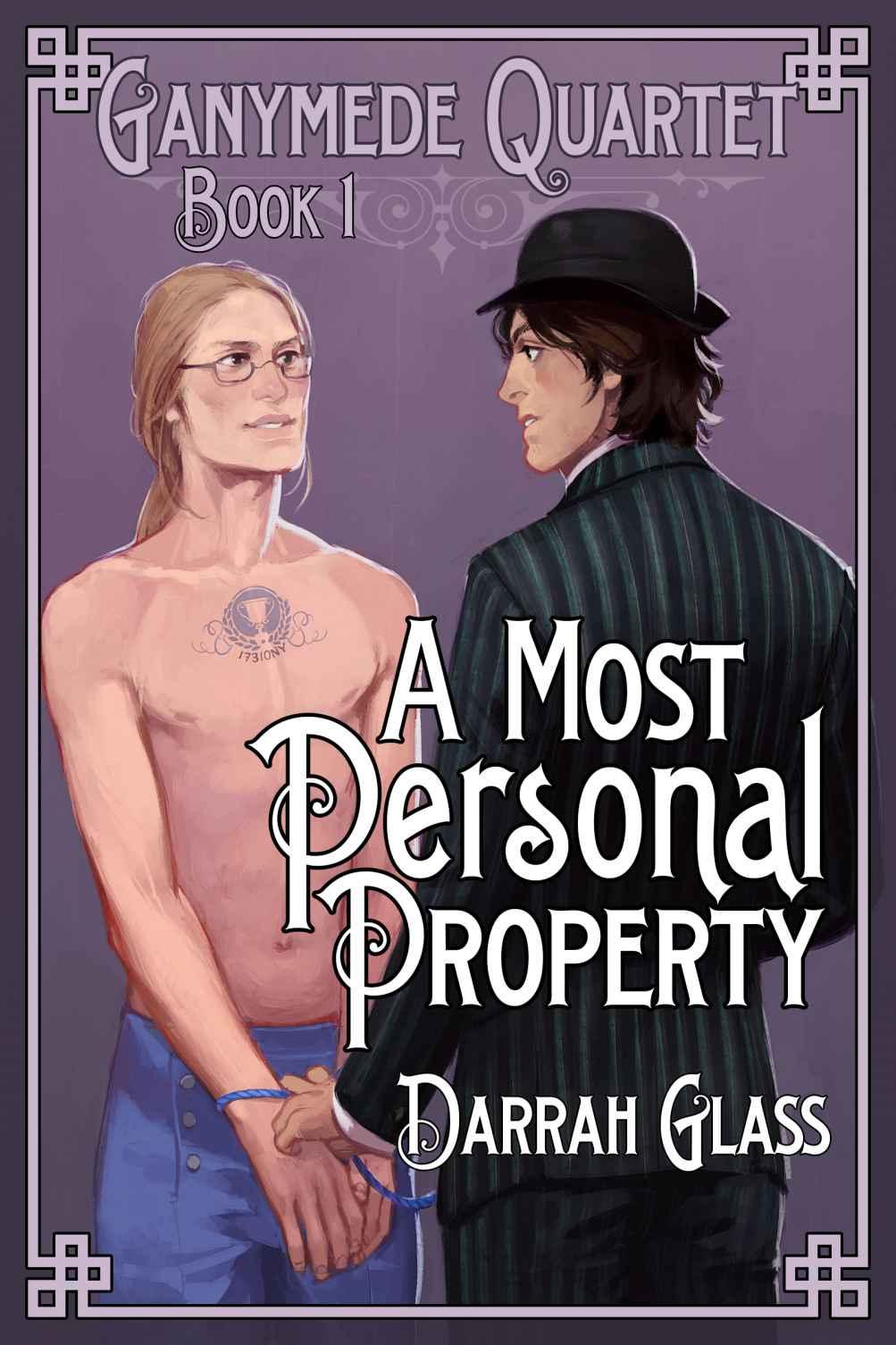

A Most Personal Property (Ganymede Quartet Book 1)

Read A Most Personal Property (Ganymede Quartet Book 1) Online

Authors: Darrah Glass

ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.

This book or any portion thereof may not be reproduced or used in any manner whatsoever without the express written permission of the author or publisher except for the use of brief quotations in a critical review.

Digital ISBN: 978-1626227224

Cover art by Ulvar

Cover design by D. Glass

For Leta, who

saved my life, with all the love she deserves.

On the last Tuesday in August, Henry Blackwell rode his bicycle in Central Park with his best friend, Louis Briggs. They made a slightly incongruous pair. Both boys were 16 and had dark hair, but Louis was short in stature and might charitably be described as plain, while Henry was quite tall and acknowledged amongst their friends to be uncommonly handsome. Henry found his good looks to be more of an encumbrance than an advantage, and felt that they led people to draw incorrect conclusions about his character. He was actually quite shy and prone to easy blushes, and grew tongue-tied in interesting company. Henry had the appearance of a leader, but did not have the stomach for it, and he had long been content to do as Louis dictated.

As they pedaled along the path, Louis chattered blithely about the slave auction on the morrow and the qualities he would be seeking in a companion slave.

“Not taller than me, of course.” Louis paused a second to think. “Not terribly freckled. I rather like a ginger, but not if it’s spotty like a Dalmatian. What about you, Henry? You’re quiet.”

“Oh, I hadn’t really much thought about it,” said Henry, which was not true. He had thought of little but what he might like in regard to a companion slave, that most personal of properties, for weeks now. “You like gingers?” Henry was surprised he had not known this.

“I do,” affirmed Louis. “But not as much as blondes. I’ll marry a blonde one day, you’ll see.” He coasted to a stop in front of the Briggs house, dragging the toes of his boots, and Henry followed suit. “So it’s a blond fellow for me, or maybe a ginger, and

not

tall.”

Henry was afraid to say anything, afraid that even stating a preference for a particular hair color would lead to saying all sorts of things best kept to himself. “I’m sure you’ll find one you like,” he said blandly.

Louis regarded him with a slight frown, seeming disappointed in him. “I don’t understand why you’re not more excited. We’ve been waiting for this for

years

.”

Henry shrugged, unwilling to share his concerns. “I’m just tired, I guess.”

Louis did not look as though he believed this, but he let it pass. “Well, g’bye, Henry. I’m sure I’ll see you tomorrow at the auction.”

Henry fervently hoped that he would indeed see Louis at the auction hall and that he, too, would be acquiring his own companion slave before the beginning of fall term at The Algonquin School, but he didn’t feel like he could count on it.

Distressingly, Henry’s school friends all seemed confident they would be acquiring companion slaves. While Henry fretted alone, his friends were being invited into confidence with their fathers, uncles, and older brothers, and receiving serious talks about responsibility and ownership. They were given slaps on the back and even the occasional sip or two of scotch to welcome them into manhood. Henry had not been met with any such ritual. He had hoped for an invitation into Father’s study, but none had been forthcoming. Now, with the auction less than a day away, Henry was sick at the thought of being left behind while his friends all became slave-owning

men

.

But Henry shared none of his inner turmoil, merely saying, “Goodbye, Louis. See you.”

Louis wheeled around and pushed his bike through the gate into his yard. Henry waved at him, but Louis had already turned his back.

Henry rode toward home slowly. The purchase of this first and most important slave was a milestone in the life of every wealthy boy, an eagerly-anticipated first step on the road to manhood. Owning a companion slave was the hallmark of a quality person, an individual steeped in tradition and deserving of respect, and, not incidentally, someone with money.

Father’s money was vulgar

new

money, but he had a very large amount of it, more than any of the other boys’ fathers, and he was determined that Henry be accepted into society as a gentleman on par with the sons of all the oldest families. Whatever Henry had been given in his short life, whether it be food or horses or bespoke suits, was the best of its kind, and there was no good reason to think his father would spare any expense when it came to purchasing Henry’s companion.

However, the announcement for the companion auction had been running on the front page of the newspaper every day for over a week, yet still Father had not said a word about his plans for the sale.

Father was not in the habit of consulting Henry on matters of any importance, even those concerning Henry himself, but Henry had hoped the companion auction would be different. Why hadn’t Father given him some indication of what he planned to do? Perhaps he was displeased with him and was punishing him accordingly. He did not know what he might do to prove himself worthy at this juncture. He was obedient, undemanding, and tried not to annoy his father, and he didn’t know what else the man could want from him. It was too late to do anything about his school marks, of course, which had not been good, but poor grades were nothing new, and it didn’t seem fair for Father to deny him a companion on this basis without prior notice. There was no use asking Mother what Father intended as she was the least informed person in the household and had little influence with Father on any account. Henry hesitated to go to his father’s own companion slave Timothy, who would surely know if Father was planning to attend the auction, if only because Timothy would no doubt go directly to Father to relate everything Henry had said, and Henry felt this would show him in a particularly immature light.

Still, it would be mortifying in the utmost to return to school next week as the only boy in his class without a companion slave of his own. Henry wished he knew the best way to approach Father with his concerns, but he was at a loss.

Henry left his bicycle in the yard for someone else to put away and went into the Blackwell house.

Billy, one of the Blackwells’ twin footmen, greeted him. “Hello, Sir. Welcome home. Would you like me to help you change?”

“I suppose so,” Henry said. He could easily be lazy and loll around in his cycling costume until dinnertime, but he had grown sweaty with his exertions and might as well take the opportunity to bathe. “You’re not too busy?” He was only asking to be polite; until such time as Henry had his companion, it was Billy’s job to serve as his valet in addition to his regular duties.

“Of course not, Sir.” Billy gave Henry a generous smile. He and his brother Paul were handsome redheads, as alike as could be; if he had not grown up with them, Henry might have developed more complicated feelings for either of the brothers, but they were so familiar that he couldn’t be anything other than comfortable in their presence

As Henry mounted the staircase to the second floor, he caught a glimpse of Timothy halfway down the south corridor, ducking into Father’s study. It was early for Timothy—and thus Father—to be home, and although Henry didn’t know if this change in pattern was good or bad, he quickly decided he should speak to his father, hoping that the fact of his presence would stir Father to address the topic that so consumed Henry’s own thoughts.

“You go ahead and wait for me in my room,” Henry said. “I want a word with Father first.”

Billy blinked, surprised. “Oh. Well, certainly, Sir. I’ll be just upstairs, then.”

Father’s study was off limits, and Henry rarely went inside; usually, if he entered, it was because he was being lectured. It was entirely Father’s domain. He smoked cigars there and could often be heard laughing behind the closed door with Timothy as his only company. Henry wondered if other fathers were as close with their slaves as Father seemed to be with his. Louis’ father seemed to barely notice his own companion, who spent most of his time managing the wild young Briggses.

Henry knocked and Timothy opened the door. He was an ordinary-looking man, unusual for a companion, with mouse-grey hair and mild blue eyes, and now he wore a look of slight bafflement, clearly surprised to see Henry there.

“Young Sir,” Timothy said, recovering his composure.

The room was dark, with wood paneling and heavy green draperies, crossed swords on the wall, a buffalo’s head over the mantelpiece, and cut-crystal decanters of liquor on the sideboard. Henry was a bit intimidated by the decor; it seemed a very manly place, a place where he doubted he’d ever really belong. He clung to the doorjamb like a man hanging from a ledge.

Father sat in an armchair with a drink in his hand, looking as though he did not appreciate having his calm disrupted. He was a large man, solidly fat, his broad chest and thick belly straining his shirtfront. He had florid cheeks, sandy whiskers, and sharp blue eyes that missed nothing, and he studied Henry critically now, clearly expecting him to provide justification for this intrusion. He held the newspaper in his lap and, from where he stood, Henry could see an advertisement for the auction printed in bold type with a fancy border. Did Father not see it?

“Henry,” Father said. “What can I do for you? Do you need Timothy for something?” He looked Henry up and down, noting his sporting costume. “Do you need help to dress?”

“No, sir. I—” Here Henry flailed, having given little thought to what he might actually say that would compel his father to be more forthcoming.