A Million Years with You (44 page)

Read A Million Years with You Online

Authors: Elizabeth Marshall Thomas

Â

“Out the window,” Hall writes, “I watch a white landscape that turns pale green, dark green, yellow and red, brown under bare branches, until snow falls again.” Yes, Gaia has been doing that kind of thing for 4.5 billion years and we are part of it. Aging is part of it. If the young see the old as alien, well, perhaps that too is part of it, at least in our culture, and if they're lucky enough to live as long as we have, they too will be alien someday. By then my scattered ashes will be part of it. I'll have entered the trees at the edge of our field. I'll have entered the grass at the roots of the trees. A deer or two will eat the grass and maybe a cougar will eat the deer, because despite what Fish and Game may think, there are cougars in New Hampshire. What a nice interlude that would be, to spend time as part of a cougar.

Prologue: Gaia

1. Lynn Margulis and Karlene V. Schwartz,

Five Kingdoms: An Illustrated Guide to the Phyla of Life on Earth

, 2nd ed. (New York: W. H. Freeman, 1988), pp. 228â229.

Â

5. The Ju/wasi

1. Elizabeth Marshall Thomas,

The Old Way: A Story of the First People

(New York: Farrar, Straus & Giroux, 2006), pp. 272â273.

2. Lorna Marshall,

The !Kung of Nyae Nyae

(Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1976), p. 112.

Â

8. Uganda

1. In

Warrior Herdsmen

, the book I later wrote about the Dodoth, I changed everyone's name because in the book I sometimes discussed cattle. A tax was levied on the number of a person's cattle and some of the men had told the tax collector that they had fewer cattle than they really had. I didn't want to reveal anyone's secrets inadvertently. But that was long ago, and here I use real names.

2. This adventure appears in a slightly different form in Peter H. Kahn, Jr., and Patricia H. Hasbach, eds.,

The Rediscovery of the Wild

(Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2013).

Â

11. Warrior

1. Thomas,

The Old Way

, pp. 198, 199.

Â

14. Research

1. Personal communication from Dr. Ronald L. Tilson, biological director of the Minnesota Zoo and senior editor of

Tigers of the World

, 2nd ed. (New York: Academic Press, 2010).

2. The observation of the sleeping wolf appears in slightly altered form in Peter H. Kahn, Jr., and Patricia H. Hasbach, eds.,

The Rediscovery of the Wild

(Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2013).

3. Elizabeth Marshall Thomas,

Tribe of Tiger: Cats and Their Culture

(New York: Simon & Schuster. 1994), pp. 231â233. The text has been slightly altered.

Â

15. Writing

1. George V. Higgins,

The Friends of Eddie Coyle

(New York: Ballantine, 1981), p. 23.

2. Courtesy of Peter H. Kahn, who also sees the problem of calling an animal

it

.

3. Katherine K. Thorington and Peter D. Weigl, “Role of Kinship in the Formation of Southern Flying Squirrel Winter Aggregations,”

Journal of Mammalogy

92, no. 1 (February 2011): 180.

Â

16. A Million Years with You

1. Alan Barnard, review of

The !Kung of Nyae Nyae

by Lorna Marshall,

Africa: Journal of the International Institute

48, no. 4 (1978): 411.

Â

17. 80

1. Donald Hall, “Out the Window,”

The New Yorker

, January 23, 2012, pp. 40â43.

Passages from this book have appeared in other books and articles I have written, most especially in

The Harmless People

(New York: Knopf, 1959),

Warrior Herdsmen

(New York: Knopf, 1965),

Tribe of Tiger: Cats and Their Culture

(New York: Simon & Schuster, 1994),

The Old Way: A Story of the First People

(New York: Farrar, Straus & Giroux, 2006), and

The Rediscovery of the Wild

, edited by Peter H. Kahn, Jr. and Patricia H. Hasbach (Cambridge, MA.: MIT Press, 2013).

Acknowledgments for a memoir are quite a challenge. My friends Sy Montgomery and Peter Schweitzer, also my husband, Steve, my daughter, Stephanie, and my son, Ramsay, have helped immeasurably in the writing of this book. Not only did they provide much of the material, but they also read chapters for me, and I am grateful. Naomi Chase also read chapters for me, and I am grateful to her. The inaccuracies (which I hope are few) would be mine, however.

I am exceptionally grateful to those who helped this book be publishedâIke Williams and Hope Denekamp of the Kneerim, Williams, and Bloom Literary Agency; the book's gifted editor, Bruce Nichols; and the wonderfully accomplished copy editor, Liz Duvall. Liz saved me from misplaced commas and also such things as mistakes in addition and in the spelling of people's names. Not all publishing houses have copy editors these days. One of my other books could have used oneâin the published version I refer to a mountain in Namibia as the Drakensberg. The Drakensberg is in South Africa. The mountain in Namibia is the Brandenberg. I considered changing my name and moving to another community.

For helpful advice on many occasions, I am grateful to my friend Anna Martin. Beyond that, with the exception of Idi Amin, Mel Konner, and that stupid psychoanalyst who told me not to go to Uganda, I am grateful to everyone I've written about herein.

Life is a collection of indebtedness, and during a life as long as mine, one becomes indebted to countless peopleâfriends, relatives, in-laws, neighbors, employers, coworkers, employees, service providers, classmates, teachers, studentsâa group that in my case would include the people among whom I did fieldwork or tried to, also those who did the anthropological and wildlife research from which the fieldwork benefited, and to name them all would not be possible. That doesn't lessen my debt.

I am equally indebted to those who are not peopleâthe elephants in the Portland zoo and Namibia, the lions in Namibia, the leopard in Uganda, the bobcat who comes to the edge of our field, to say nothing of the cougar who did the same thing, probably to the consternation of the bobcat. I'm grateful to the bears in our woods, who leave messages for other bears by scratching the trees, also to the wild turkeys and to the whitetail deer, and, of course, to the wolves and the ravens of Baffin Island.

But I'm especially grateful to my dogs and cats, all of them, and to the older daughter of the whitetail doe who was killed by a cougar. Thanks to her, three deer live near the edge of our field, not just one.

I am continually filled with gratitude for these nonpeople, especially at night. One of our dogs finds our bed crowded so she sleeps on her own bed beside me, but the other dog sleeps between me and my husband. For some reason she sleeps on her back. Three of the cats also sleep with us, two curled up against us and one curled up against the dog. If a cat thinks we are awake he purrs, slightly more loudly as he inhales, slightly more softly as he exhales. Sometimes after a soft purr there's silence. The cat has dozed off.

Shortly before sunrise the dog who sleeps on her back wakes up. She descends the little staircase we built so she can get on and off the bed (she has a touch of arthritis) and she barks, but just once.

Yap

. She means that dog breakfast-time has come. I get up in the dark. The cats do too. The dog whose bed is on the floor gets up. We walk down the dark hall to the kitchen and start our day together. I couldn't ask for more.

Â

Â

I

BEGAN

observing dogs by accident. While friends spent six months in Europe, I took care of their husky, Misha. An agreeable two-year-old Siberian with long, thin legs and short, thick hair, Misha could jump most fences and travel freely. He jumped our fence the day I took him in. A law requiring that dogs be leashed was in effect in our home city of Cambridge, Massachusetts, and also in most of the surrounding communities. As Misha violated the law I would receive complaints about him, and with the help of these complaints, some from more than six miles distant, I soon was able to establish that he had developed a home range of approximately 130 square miles. This proved to be merely a preliminary home range, which later he expanded considerably, but interestingly enough, even young Misha's first range was much larger than the ranges of homeless dogs reported in Baltimore by the behavioral scientist Alan Beck. Beck's urban strays had established tiny ranges of but 0.1 to 0.06 square mile. In contrast, Misha's range more closely resembled the 200-to 500-square-mile territories roamed by wolves, most notably the wolves reported by Adolph Murie in “The Wolves of Mount McKinley” and by L. David Mech in “The Wolves of Isle Royale.” What was Misha doing?

Obviously, something unusual. Here was a dog who, despite his youth, could navigate flawlessly, finding his way to and from all corners of the city by day and by night. Here was a dog who could evade dangerous traffic and escape the dog officers and the dognappers who at the time supplied the flourishing laboratories of Cambridge with experimental animals. Here was a dog who never fell through the ice on the Charles River, a dog who never touched the poison baits set out by certain citizens for raccoons and other trash-marauders, a dog who never was mauled by other dogs. Misha always came back from his journeys feeling fine, ready for a light meal and a rest before going out again. How did he do it?

For a while I looked for the answer in journals and books, availing myself of the fine libraries at Harvard and reading everything I could about dogs to see if somewhere the light of science had penetrated this corner of dark. But I found nothing. Despite a vast array of publications on dogs, virtually nobody, neither scientist nor layman, had ever bothered to ask what dogs do when left to themselves. The few studies of free-ranging dogs concerned feral dogs, abandoned or homeless dogs. Alone in hostile settings, these forsaken creatures were surely under terrible stress. After all, they were not living under conditions that were natural to them, any more than are wild animals in captivity, imprisoned in laboratories and zoos. How might dogs conduct themselves if left undisturbed in normal circumstances? No one, apparently, had ever asked.

At first, that science had ignored the question seemed amazing. But was it really? We tend to study animals for what they can teach us about ourselves or for facts that we can turn to our advantage. Most of us have little interest in the aspects of their lives that do not involve us. But dogs? Dogs do involve us. They have shared our lives for twenty thousand years. How then had we managed to learn so little about dogs that we could not answer the simplest question: what do they want?

Our ignorance becomes more blameworthy when we consider that no animal could be easier to study. Unlike wild animals, dogs are not afraid of us. To study them we need not invade their habitat or imprison them in oursâour world

is

their natural habitat and always was. Furthermore, because their wild ancestors were not dogs at all but wolves, dogs have never even existed as a wild species. As a result we have had the opportunity to observe dogs since dogs began, an opportunity that for the most part we have chosen to ignore. Hence, curled on the sofa beside me of an evening was a creature of mystery: an agreeable dog with a life of his own, a life that he had no wish to conceal and that he was managing with all the competence of a wild animal, not with any help from human beings but in spite of them.

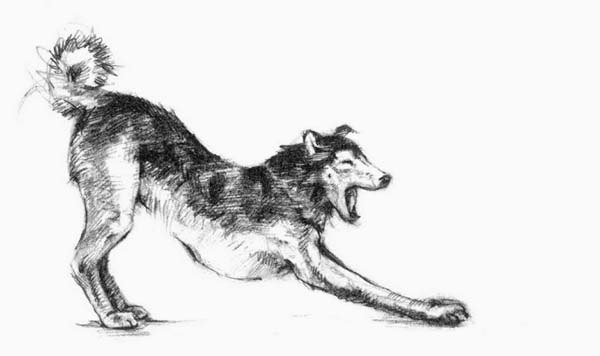

One evening he got up and stretched, preparatory to voyaging. First he braced his hind legs and stretched backward, head bowed, rump high, to pull tight the muscles of his shoulders. Then he raised his head and dropped his hips to stretch his spine and hind legs, even clenching his hind feet into fists so that the stretch went into his toes. Ready at last, he moved calmly toward the door so that, as usual, I could open it for him. And then, as our eyes met, I had an inspiration. Misha himself would answer my questions. Right in front of me, a long-neglected gate to the animal kingdom seemed waiting to be opened. Misha held the key.