A Lucky Child: A Memoir of Surviving Auschwitz as a Young Boy (21 page)

Read A Lucky Child: A Memoir of Surviving Auschwitz as a Young Boy Online

Authors: Thomas Buergenthal,Elie Wiesel

Tags: #Biography & Autobiography, #General, #United States, #Biography, #Social Science, #Personal Memoirs, #Europe, #History, #Historical, #Military, #World War II, #World War; 1939-1945, #Holocaust, #Jewish Studies, #Eastern, #Poland, #Holocaust survivors, #Jewish children in the Holocaust, #Buergenthal; Thomas - Childhood and youth, #Auschwitz (Concentration camp), #Holocaust survivors - United States, #Jewish children in the Holocaust - Poland, #World War; 1939-1945 - Prisoners and prisons; German, #Prisoners and prisons; German

Letter from Odd Nansen to Thomas

As we started to open the wooden crate the soldiers had delivered from Mr. Nansen, I kept chiding Mutti. “I told you his father

was not a cookie manufacturer! Nobody believed me that I would find him or that my letter would reach him. See, it reached

him even without a proper address,” I kept gloating. The crate was filled with the most marvelous food items: cans of sardines

and herring, condensed milk, dried fruit, rice, flour and sugar, a variety of crackers, and many, many chocolate bars and

other candy. Mutti and I just stood there in total disbelief. Who had ever seen so much food or even tasted it? At the time,

food was still severely rationed in Germany, and even with the food packages we received from the American Joint, we never

had enough, nor anything as “exotic” as this shipment. We were in seventh heaven and in the days to come ate more chocolate

than was good for us. Later I learned that Norwegian schoolchildren had collected the chocolate and candy for me. They started

this campaign after Norwegian newspapers reported that I was alive and living in Göttingen. Because Odd Nansen had dedicated

his book to “the living memory” of some of his friends from camp and to “you too, little Tommy!” and had described me in his

book as the “Angel Raphael of the

Revier,

” I had become famous in Norway and something of a hero to the country’s children. In the meantime, the three-volume book

arrived with the following inscription:

Dear Tommy, here is my camp diary. As you will see, it is also dedicated to you. Even though you will not be able to read

it in Norwegian, I want you nevertheless to have it as a present from a person who came to love you and one who never forgot

nor ever will forget his young friend, that little brave angel from

Revier

No. III in Sachsenhausen.

Not long thereafter, Mr. Nansen came to Göttingen and arranged for me to visit him and his family in Norway. It was not all

that easy for me to make that trip because I did not have a proper passport. Sometime after Mutti returned to Göttingen, she

was offered her German citizenship back. She declined it, telling the official who had come to see her, “You took it away;

now you can keep it!” That meant that we did not have a German passport and were only eligible for a stateless one. I eventually

got such a passport and a visa for travel to Norway. Mutti and I met Mr. Nansen in Hamburg, from where he and I flew to Oslo.

At the airport, Mr. Nansen introduced me to a German he identified as “my good friend, Mr. Willy Brandt, who fought against

the Nazis in the Norwegian resistance.” Of course, at the time, I had no idea who Willy Brandt was — I think he was deputy

mayor of Berlin when we met. Years later, I would proudly claim that I knew Willy Brandt long before he became famous as West

Germany’s chancellor.

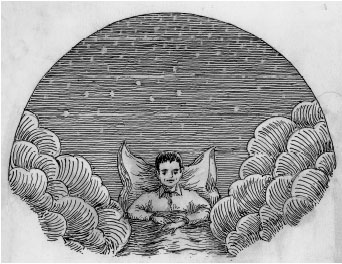

“The Angel Raphael of the Revier,” drawing by Odd Nansen

My trip to Norway was filled with one adventure after another. For one thing, I had never flown in an airplane before, which

in itself was a thrilling experience. It was followed by a press conference at the Oslo airport, where I had to answer hundreds

of questions. The Nansen family, including Mrs. Nansen and their four children — Marit, Eigil, Siri, and Odd Erik — treated

me like a beloved, long-lost family member. Mr. Nansen also arranged for me to meet many former Sachsenhausen inmates who

knew me from the camp, among them — if I remember correctly — a prime minister and other high government officials and leading

personalities. I felt very important, of course, although I most enjoyed being able to swim with the Nansen kids in the Oslofjord,

which abutted the Nansen family property. I had never even been near the sea, and the Oslofjord and the surrounding mountains

were a very special experience for me. I also went with the Nansen family to their cottage in the mountains. Mr. Nansen was

an architect by profession and an excellent painter. His camp diary contained many sketches of inmates and Nazi guards, and

his home in Oslo was filled with these and other paintings and drawings. Fun conversations and reminiscences enlivened our

dinners. I even learned some Norwegian words because it was decreed that one day a week the dinner language would be Norwegian,

and if I wanted to eat, I had to ask for the food in Norwegian. That proved to be a strong incentive to learn the necessary

words.

Thomas with Odd Nansen, 1951

The trip back to Germany turned out to be most unpleasant. Some American friends of the Nansens were scheduled to travel by

train to Copenhagen via Sweden on the same day I was to leave Oslo. The Nansens thought that it would be fun for me to have

an opportunity to see Copenhagen, and especially the Tivoli, in the company of these friends as I made my way back to Germany.

My plane ticket was traded in for a train ticket, and we were on our way. But I did not get very far. I was stopped at the

border between Sweden and Norway. Since I did not have transit visas for Sweden and Denmark, which I needed as a stateless

person, I was not allowed to proceed. That meant that I had to return to Oslo, where the Nansens obtained the necessary visas

for me. Back in Göttingen, about six weeks later and without ever having stopped to see Copenhagen, I told Mutti what problems

I had encountered with my stateless passport. She was quite upset that her stand on principle should now cause added hardship.

“To hell with principle,” she said, and a day later applied for the return of our German citizenship.

When the German translation of Odd Nansen’s book appeared in 1949, he noted in the introduction that he was donating the proceeds

of that volume to a fund set up to help German refugees. That made me wonder why a man who had spent more than three years

in a Nazi concentration camp would care about the fate of these people. After some time, I began to think that it was important

that individuals like Nansen and the rest of us who had been subjected to terrible suffering at the hands of the Germans treat

them with humanity, not because we sought their gratitude or wanted to show how generous in spirit we were, but simply because

our experience should have taught us to empathize with human beings in need, regardless of who they were. At the same time,

of course, I was convinced that those Germans who ordered or committed the crimes the Nazis were responsible for should be

punished, not Germans in general simply because they were Germans. That is why I also came to realize that the machine gun

I wanted to mount on our balcony when I first arrived in Göttingen was a shameful idea. I concluded that even to contemplate

that action reduced me to the level of those Germans who had killed innocent human beings. What is more, it dishonored the

memory of those who had died in the camps. As time passed, these early random reflections came to solidify into convictions

that influenced my thinking and actions later in life.

In 1951, shortly before I left Germany for the United States, Odd Nansen delivered a keynote address at an event organized

to coincide with the conferral of the German Peace Prize on Albert Schweitzer, the famous humanitarian, by the Association

of German Booksellers and Publishers. Mutti and I were invited to both events. The Schweitzer ceremony took place in the historic

St. Paul’s Church in Frankfurt. I knew, of course, who Schweitzer was and was very moved when Nansen introduced me to him.

In his speech, delivered a day earlier, Nansen called on the international community to address the plight of German refugees.

At the time, the question of whether Germany should be allowed to participate in the 1952 Olympics was still being debated

around the world. In his speech, Nansen urged a favorable decision with the following words: “It is unjust and senseless to

punish the children for the sins of their fathers. But that is what is sought to be done when Germany’s young people are kept

out of associations [designed to promote] international cooperation.”

The theme of the conference, with its focus on peace and human dignity, had a profound impact on me in terms of the values

to which I have devoted much of my life. I still have a doge-ared copy of Nansen’s speech and a photograph of Schweitzer holding

a kitten. Taking in the pomp and ceremony that surrounded us in that church — the first such event I had ever attended — I

turned to Mutti, who was with me, and whispered, “Who would ever have thought that we would be allowed into this historic

cathedral? Not all that long ago we were

Untermenschen

[subhumans], and now we are invited guests. If only Papa could be with us on this occasion.” Over the years, I have thought

often of my father when attending similar ceremonies in Germany and Austria. He who believed that Hitler and the Nazis would

sooner or later be defeated never had the satisfaction, unfortunately, of seeing that he was right and witnessing the transformation

of Germany into a democratic state.

Nansen came to Göttingen before the Frankfurt conference and told Mutti and me that he wanted to write a book about our camp

experiences. He had apparently received many letters from the readers of his diary, urging him to tell my story in full. We

agreed, of course, to be interviewed by Nansen for the book and spent a few days answering his questions. Although we remained

in contact with Nansen in the years that followed, we heard nothing more about the book and assumed that he had decided not

to write it. Nineteen years later, in 1970, his book

Tommy

was published in Norway.

*

He immediately sent me a copy. The long delay in getting the book out, Nansen explained, was due to the fact that in the

intervening years he had been extremely busy in his architecture firm and had to put the book project aside. But, in 1969,

he fell ill and was ordered by his doctors to give up his architecture practice. With time on his hands, he went back to his

notes from the 1951 interview with Mutti and me and wrote the book.

Tommy

was published only in Norwegian. Nansen died a couple of years later without getting the book published in any other language.

Fortunately, I saw Nansen before he died. While attending a human rights conference in Sweden, I decided to delay my return

flight to the United States so I could spend a few days visiting him in Oslo. I did not realize how sick he was and was shocked

to find him in such bad health. He refused to talk about his health and kept telling me instead that he was delighted that

I was involved in human rights work. Of course, he did not want to hear that he more than anyone else was responsible for

my choosing to embark on this career path. I learned only later that he was one of the cofounders of UNICEF. That did not

really surprise me. After all, I was one of the beneficiaries of his lifelong commitment to helping children in need.

It was not until 1985, my final year as dean of American University Washington College of Law in Washington, D.C., that I

was finally able to read

Tommy

. As my office was preparing the program for the last graduation ceremony I was to preside over as dean, I was asked by the

president of the Law Students Association to permit him during the ceremony to say a few words on behalf of the graduating

class. Of course I agreed, and when the time came, I invited him to take the floor. He walked up to the podium, unwrapped

a package in a black binder, and told the audience that it was the English translation of

Tommy

. Explaining that

Tommy

was a book about my experiences during the Second World War, he continued, “Dean Buergenthal, the graduating class has commissioned

this private English translation of

Tommy

as a token of our appreciation for you so that you will finally be able to read the book that tells your story.” When I was

handed the translation of

Tommy,

I just stood there, overwhelmed by emotion and unable to say a word.

*

It took me quite a while before I was able to continue with the prescribed graduation program.

During the years I spent in Göttingen, Germany underwent dramatic changes, particularly as far as the economic recovery of

the country was concerned. The 1948 currency reform, which enabled us to exchange the largely worthless Reichsmarks for the

new D-Marks, made a great impression on me because, almost overnight, empty store windows were filled with products I had

never seen before. I think it was during that period that I ate my first orange. As I was eating it, Mutti told me that oranges

were full of vitamin C and that, because they were very expensive and still difficult to obtain, they could only be bought

when needed to ward off a cold or influenza. It was also about this time that I had my first taste of Coca-Cola. I don’t know

from whom or where Mutti obtained the bottle. Mutti showed it to me and told me that she had heard that it was a very special

drink that quenched one’s thirst with only a few sips and that I should drink it only when I was particularly thirsty. She

then put the bottle into the cupboard — we did not have refrigerators in those days — and there it sat until I came home one

day, terribly thirsty from hours of playing soccer. Mutti agreed that the time had come to open the Coke bottle. The more

I drank that sweet, lukewarm drink, the thirstier I got. For years afterward, I only had to look at a bottle of Coca-Cola

to be reminded of the unpleasant taste of my first sip.