A Lovesong for India (12 page)

Read A Lovesong for India Online

Authors: Ruth Prawer Jhabvala

The end of August was very hot, and since the only air conditioning was in the salon, Som spent the last few nights before his departure sleeping on the roof. Too stout and breathless to be able to follow him, Anuradha stood at the foot of the stairs to call up to him. When there was no answer, she sent Maria with some message invented on the spur of the moment; this Maria recognised to be only an unnecessary pretext to assure him that his mother loved him. Maria went to the foot of the stairs, stood there for a while and returned to say that Som was asleep. Anuradha smiled at the thought of her son sweetly asleep on the roof of her house; but mixed in with her smile there was something sad, a nostalgia for her own nights on that same roof, years ago when she could still get up there.

Those nights continued to exist in a cycle of poems she had written about them, and it was these she was now inspiring Maria to translate. They spoke of the sky above the roof veiled in night and pierced by stars, and the new moon, frail as jasmine, set above a nearby minaret. But mostly they were about the lovers who had rolled around up there with Anuradha, one hand on her mouth to stifle her screams for fear of arousing her father asleep downstairs. And in later years it was not the father but the husband in bed downstairs, and one night Anuradha discovered that he was not asleep. From beneath her lover (a minor poet), she opened her eyes and met those of her husband gazing at her from the entrance to the roof. By the time she had freed herself from the embrace, her husband had gone, so that she might have taken her vision to be imaginary. Yet she knew he had been there and that he had seen. Next day, apart from a slight contraction of his lips, he was his usual tender self with her, as silently understanding as no one, no other human being had ever been with her. And for that she loved him the way she had never loved anyone – no, not even those lovers up there under the stars who had aroused her to an ecstasy that made her completely forget the husband she so loved.

This stanza about the husband was the end of the cycle that Maria translated. It was also the end of her sabbatical, and Anuradha arranged a farewell party for her last evening. Maria knew very well that it was not her last evening but Som’s. Fortunately, with his own farewell parties given for him by his colleagues, Som was rarely at home; and when he did return, he crept straight up to the roof. Anuradha several times sent Maria to inform him about the party – ‘And the time! Make sure he knows the time!’ for, like herself, Som was habitually late. Maria again went to the foot of the stairs and stood there for a while before returning to reassure Anuradha.

The evening party was attended by poets and musicians, some of them famous, others half starved. Leaving their shoes on the threshold, they crowded into the salon and sat on the carpet with their naked feet tucked under them. The air was suffused with the heavy perfumes worn by the wealthier artistes and the cheap bazaar ones by the others; also, mixed in with the spiced delicacies brought in from the cook-house, there was the smell of the fierce little brown cigarettes, many of them chain-smoked along with Anuradha. A lot of teasing went on, mainly of one famous old poet who was half paralysed and sat in a wheelchair. The fun revolved around the coquetry of his manner and of his dress – the finest Lucknow kurtas, bracelet and earrings to attract the young girls he still so ardently desired. He didn’t deny it, and contentedly chewing his betel, he quoted famous verses in Persian and Urdu from dead old poets renowned for their undiminished libido.

Anuradha, shining in purple silk, reclined on the divan; at her feet, Maria was perched on a stool, clutching the pages of her translation from which she was to read. Anuradha hissed at her, ‘Are you sure you told him?’, for Som had not yet appeared. And again, ‘Are you sure you told him the right time?’ Maria couldn’t answer, her mind was confused by the fear about the secret departure, as well as the fear of reading her translations before this assembly of experts.

At last Anuradha decided she could delay no longer. She intoned the original of one of her stanzas and, waiting for the ecstasy of her audience to subside, she signalled to Maria to read out her translation.

Maria was so nervous that she dropped some of her papers and had to be helped by the nearest poet to retrieve them. Then she discovered the pages had got mixed up, so that she was no longer sure her translation was of the stanza Anuradha had recited. It made no difference – she knew that whatever she read couldn’t in any way come up to the sonorous sounds of the original that still reverberated in the salon. She saw Anuradha frown, her dissatisfaction with Maria exacerbated by Som’s failure to appear. ‘You forgot to tell him,’ she accused Maria – and then she launched into another grand and glorious recitation, eliciting more cries of pain and joy from her admirers.

Maria tried to read her translation; but aware of her inadequacy, she trembled so much that she could hardly go on. The paralysed poet took pity on her and began to declaim one of his own compositions. This swept over the audience with the same effect as Anuradha’s, though his way was more delicate, more feminine, and – quite unlike Anuradha – submissive and accepting. But passionate too, and with a force that made Maria tremble with excitement. Far from being cast down by her own failure, she felt exalted to be in the company of these poets. Behind her gold-rimmed spectacles, her pale eyes shone with new resolve – to dedicate herself completely to Anuradha, to be guided and moulded by her, to become worthy of her.

And when everyone, deeply satisfied with the evening’s entertainment, had taken their leave, Maria wanted to

declare

herself to Anuradha. But even if she had been able to find the right, or any, words for this, Anuradha didn’t give her a chance. She indicated the papers in Maria’s hand: ‘Tonight you heard the difference: the waters flowing from a living heart and this – this – a stagnant pond; a wooden tongue.’ Snatching the pages, she threw them to the floor, and then she poured out the kind of invective she usually reserved for her servants, her tenants and for Som; and maybe some of it was meant for him, for not being there.

declare

herself to Anuradha. But even if she had been able to find the right, or any, words for this, Anuradha didn’t give her a chance. She indicated the papers in Maria’s hand: ‘Tonight you heard the difference: the waters flowing from a living heart and this – this – a stagnant pond; a wooden tongue.’ Snatching the pages, she threw them to the floor, and then she poured out the kind of invective she usually reserved for her servants, her tenants and for Som; and maybe some of it was meant for him, for not being there.

It was at this moment that he arrived home from his own farewell party. Hearing his mother’s furious voice from the salon, he opened the door – Anuradha saw him at once. She shouted, ‘Where were you? Everyone was asking, “Where is your son?” And I had to say, “No, I have no son!”’

Bewildered, Som looked at Maria – at once Anuradha pounced on her. ‘You didn’t tell him!’ Before Maria could protest – ‘You’re lying!’ Anuradha cried.

Maria hid her guilty face by bending down for her scattered papers. Som tried to help her, but his mother commanded, ‘Give them here!’ She took the pages from him, then tore them across, first one, then another, then all the rest, flashing bolts of fury out of her kohl-rimmed eyes.

It was a relief to Maria to take refuge in her own room. But that night she was entirely sleepless, and finally she tiptoed back to the salon. She put her ear to the door and heard Anuradha sighing and muttering to herself. She called timidly for permission to enter, but Anuradha wouldn’t let her. ‘I’m displeased!’ she called back. The word ‘displeased’ pleased Maria – it was mild, it could easily be overcome. Probably soon Anuradha herself would call for her. Maria sat waiting for this call in her little room. Her spuriously packed suitcase stood open, and she decided to unpack it the next day, after she and Anuradha had got up and Som would have left.

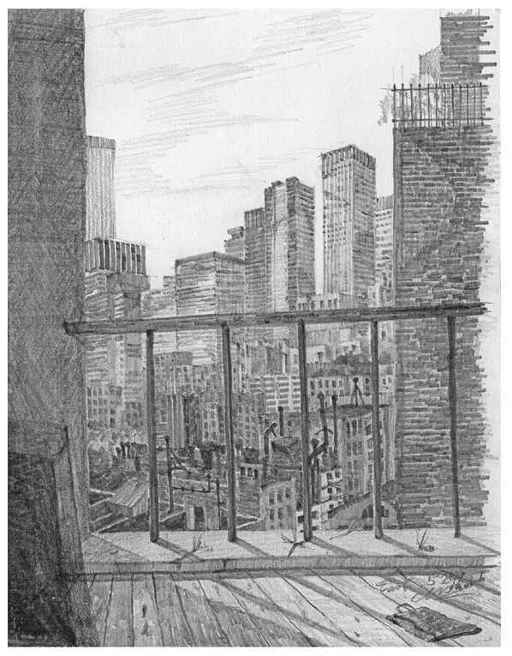

Suddenly she remembered that she hadn’t given him the key to her apartment in Boston. Very quietly, though alert in case this was the time Anuradha decided to call for her, she made her way up the stairs to the roof. How different it was here from the nights of Anuradha’s poetry. There were no stars or moon visible in a sky overhung with pollution; and instead of the scent of flowering bushes, the air was thick with some smell acrid enough to be burning rubber tyres.

Som was awake, slapping at the mosquitoes that whined around him. As soon as he saw Maria, he said, ‘When she finds out that I’ve gone and we’ve lied to her – no, I can’t leave.’

But he

had

to leave! ‘Don’t worry,’ she said. ‘I’m here to care for her. Don’t worry at all. You mustn’t.’ A mosquito sat quite blatantly on her cheek; she let it, alert to not missing a call from downstairs.

had

to leave! ‘Don’t worry,’ she said. ‘I’m here to care for her. Don’t worry at all. You mustn’t.’ A mosquito sat quite blatantly on her cheek; she let it, alert to not missing a call from downstairs.

He said, ‘I can’t run off to Boston and leave you alone with her. After all, she’s

my

responsibility, not yours.’

my

responsibility, not yours.’

‘No,

mine

,’ Maria almost exclaimed – too passionately, she felt at once, so she continued in a different tone, in her scholar’s voice: ‘You know the Sanskrit word

Sraddha

? No, it’s not your field.’ She smiled, remembering what Anuradha said about his studies, which she compared to a donkey being made to pull a load of useless books up a mountain. ‘

Sraddha

,’ she explained. ‘The attitude of the aspirant to the guide. This attitude is of devotion; of faith and reverence; of obedience.’

mine

,’ Maria almost exclaimed – too passionately, she felt at once, so she continued in a different tone, in her scholar’s voice: ‘You know the Sanskrit word

Sraddha

? No, it’s not your field.’ She smiled, remembering what Anuradha said about his studies, which she compared to a donkey being made to pull a load of useless books up a mountain. ‘

Sraddha

,’ she explained. ‘The attitude of the aspirant to the guide. This attitude is of devotion; of faith and reverence; of obedience.’

‘Yes. Everything she’s always wanted from me and everyone else in the world . . . She’s trying to come up,’ he said with alarm at the sound of a step on the stairs.

‘She’s trying to come to me,’ Maria said. ‘That’s there too in our word: not only the desire of the student for the master but that of the master for the student. Sanskrit has so many levels of meaning. For instance, besides everything else,

Sraddha

means pregnancy.’ Caught up in her favourite subject, she was about to tell him that pregnancy here carried the sense of yearning – the way a pregnant woman yearns for something that alone will satisfy her deepest appetite. But she stopped herself, considering him not ready for such esoteric knowledge. Instead she said, ‘Your taxi is coming at six a.m. I’ll be with her all night, and by morning she’ll be fast asleep. She won’t hear a thing.’

Sraddha

means pregnancy.’ Caught up in her favourite subject, she was about to tell him that pregnancy here carried the sense of yearning – the way a pregnant woman yearns for something that alone will satisfy her deepest appetite. But she stopped herself, considering him not ready for such esoteric knowledge. Instead she said, ‘Your taxi is coming at six a.m. I’ll be with her all night, and by morning she’ll be fast asleep. She won’t hear a thing.’

More clumping footsteps could be heard on the stairs, and Som became desperate: ‘She’ll fall, she’ll twist her ankle, sprain her wrist – it’s happened before; and then of course I have to stay – what good son wouldn’t be there for his mother?’

‘Here’s the key,’ Maria said. ‘One is for the upper lock – you’ll have to work it out, which is which.’

She hurried to the top of the stairs. She saw that Anuradha had reached the third step and there she had to sit and rest. She looked up at Maria, and there was something so piteous in her look that, without a backward glance at Som, Maria ran down to her. She squeezed herself beside her on the third step; she twined her long thin arms around the massive poetess, she whispered in her ear, ‘Anuradha, Anuradha.’

Whatever had been Anuradha’s intention of calling for her – whether it was to curse, insult or to beg for her forgiveness – now, as that whisper of her name dropped down into her fiery soul, Anuradha, like Maria, thought only of the work that lay ahead of them, the hours and days and months and years of their nights of poetry, their wild nights together.

MOSTLY ARTS AND ENTERTAINMENT

Talent

Although highly organised in her office – she was a talent agent – at home Magda was terribly untidy. ‘How can you live like that,’ her mother said, whenever she came to visit her. But she wasn’t encouraged to come often. No one was: Magda liked to keep her place to herself. She didn’t have many personal friends. All her time was taken up by business, her lunches, her dinners, even breakfasts were turned into conferences. Only weekends were free; and by the time they came around, she didn’t feel like seeing any more people, and anyway there was no one to see once the offices were closed and everyone left for their weekend places or plans. Magda stayed mostly in bed, reading the newspapers; if the telephone rang, it was always her mother asking if she was coming to see her. Magda said yes, she would come, although by Sunday afternoon she usually decided she wouldn’t but would just stay where she was until everything began again on Monday morning. She dug herself deeper into her crumpled bedclothes, only getting up to heap plates of leftovers for herself from the refrigerator. Often Sunday nights she couldn’t sleep, from indigestion caused by excessive amounts of stale food eaten too quickly. Her sheets were stained with grease and with the tears she shed, usually without cause, or any that she knew of.

All this changed after she met Ellie. For one thing, she cleaned up her apartment. She threw out long-discarded papers, wiped her grimy windows – she stood on a ladder, whistling as she reached up high to rub and shine. It was like a new beginning; it

was

a new beginning. Yet her first meeting with Ellie had not been auspicious. She hadn’t cared for the way Ellie had dawdled into her office, with no idea what a big favour had been extended to her, a completely unknown young English girl. Magda was doing this favour for one of her colleagues, who had asked her to give a few minutes of her time to what might turn out to be a new talent. Five minutes was all Magda did give – she had a string of other appointments and was certainly not going to put herself out for this ungracious girl. When Ellie sauntered out, as casually as she had sauntered in, she left a tape on the desk, which Magda failed to see and might very well have thrown in the trash if she had; but her secretary conscientiously put it in Magda’s briefcase, where she discovered it in searching for something more important. This happened at the end of one of those long empty weekends, so that Magda played it out of boredom, with no expectation at all. But the voice that emerged from the player startled her; she played the tape again, and then again. Next day she sent for Ellie – not to the office but to the French Pavilion where she gave her a big expense-account lunch.

was

a new beginning. Yet her first meeting with Ellie had not been auspicious. She hadn’t cared for the way Ellie had dawdled into her office, with no idea what a big favour had been extended to her, a completely unknown young English girl. Magda was doing this favour for one of her colleagues, who had asked her to give a few minutes of her time to what might turn out to be a new talent. Five minutes was all Magda did give – she had a string of other appointments and was certainly not going to put herself out for this ungracious girl. When Ellie sauntered out, as casually as she had sauntered in, she left a tape on the desk, which Magda failed to see and might very well have thrown in the trash if she had; but her secretary conscientiously put it in Magda’s briefcase, where she discovered it in searching for something more important. This happened at the end of one of those long empty weekends, so that Magda played it out of boredom, with no expectation at all. But the voice that emerged from the player startled her; she played the tape again, and then again. Next day she sent for Ellie – not to the office but to the French Pavilion where she gave her a big expense-account lunch.

Other books

Plum Deadly by Grant, Ellie

The Jeeves Omnibus - Vol 2: (Jeeves & Wooster): No. 2 by Wodehouse, P.G.

Taken by the Alien Lord by Jennifer Scocum

Dawson's Fall (Welcome to Covendale #5) by Morgan Blaze

Social Skills by Alva, Sara

Miss Marianne's Disgrace by Georgie Lee

Desert Guardian by Duvall, Karen

Aunt Dimity: Detective by Nancy Atherton

5 Beewitched by Hannah Reed