A Little History of the World (31 page)

Read A Little History of the World Online

Authors: E. H. Gombrich,Clifford Harper

So instead Charles V ordered the rebellious monk to present himself before the first parliament that Charles was to hold in Germany. This was in Worms, in 1521. All the princes and great men of the empire were there, in a solemn and splendid assembly. Luther came before them dressed in his monk’s cowl. He had already made it known that he was ready to renounce his teaching if it could be shown from the Bible to be wrong – for as you know, Luther would accept only what was written in the Bible as the word of God. The assembled princes and noblemen had no wish to become trapped in a war of words with this ardent and learned Doctor of Theology. The emperor ordered him to renounce his teaching. Luther asked for a day to think. He was determined to hold fast to his convictions, and wrote at the time to a friend: ‘Truly, I shall not renounce even one letter of it, and put my trust in Christ.’ The next day he appeared again before the assembled princes and noblemen of the parliament and made a long speech in Latin and German, in which he set out his beliefs. He said he was sorry if, in his zeal to defend himself, he had given offence, but recant he could not. The young emperor, who had probably not understood a word, told him to answer the questions clearly and come to the point. To this Luther replied heatedly that only arguments drawn from the Bible would compel him to recant: ‘My conscience is bound by the word of God, and for that reason I can and will renounce nothing, for it is dangerous to act against one’s conscience … So help me God. Amen.’

The parliament then passed an edict declaring Luther an outlaw, which meant that nobody was allowed to give him food, aid or shelter. If anyone did, they too would be outlawed, as would anyone caught buying or in possession of his books. Nor would anyone be punished for his murder. He was, as they put it, ‘free as a bird’. But his protector, Frederick the Wise, had him kidnapped and taken in secret to his castle, the Wartburg. There Luther lived in disguise and under a false name. He took advantage of his voluntary captivity to work on a German translation of the Bible so everyone could read it and think about its meaning. However, this was not as easy as it sounds. Luther was determined that all Germans should read his Bible, but in those days there was no language that all Germans could read: Bavarians wrote in Bavarian, Saxons in Saxon. So Luther had to invent a language that everyone could understand. And in his translation of the Bible he actually succeeded in creating one that, even after nearly five hundred years, is not all that different from the German that people write today.

Luther stayed in the Wartburg until one day he heard that his speeches and writings were having an effect which did not please him at all. His Lutheran followers had become considerably more violent in their zeal than Luther himself. They were throwing paintings out of churches and teaching that it was wrong to baptise children, because everyone had to decide for themselves whether they wished to be baptised. People called them Iconoclasts and Anabaptists (destroyers of images and re-baptisers). Moreover, there was one aspect of Luther’s teaching that had had a profound effect on the peasants, and which they had taken very much to heart: Luther had taught that each individual should obey the voice of his own conscience and no one else and that, subject to no man, should freely and independently strive for God’s mercy. The feudal peasant serfs understood this to mean that they should be free men. Armed with scythes and flails they banded together, killing their landlords and attacking monasteries and cities. Against all these Iconoclasts, Anabaptists and peasants, Luther now turned the full force of his preaching and writings, just as he had previously used them in his attacks on the Church, and so he helped crush and punish the rebel bands. This lack of unity among Protestants, as Luther’s followers were called, was to prove very useful to the great, united, Catholic Church.

For Luther wasn’t alone in thinking and preaching as he did during those years. In Zurich a priest called Zwingli had taken a similar path, and in Geneva another learned man named Calvin had distanced himself from the Church. Yet despite the similarities of their teachings, their followers could never bring themselves to tolerate, let alone live with, one another.

But now there came a new and even greater loss for the papacy. In England, King Henry VIII was on the throne. He had married Catherine of Aragon, an aunt of the emperor Charles V. But he didn’t like her. He wanted to marry her lady-in-waiting, Anne Boleyn, instead. When he asked the pope, as head of the Church, to grant him a divorce, the pope refused. So, in 1533, Henry VIII withdrew his country from the Roman Church and set up a Church of his own, one that allowed him his divorce. He continued to persecute Luther’s followers, but England was lost to the Roman Catholic Church for ever. It wasn’t long before Henry was tired of Anne Boleyn as well, so he had her beheaded. Eleven days later he remarried, but that wife died before he could have her executed. He divorced the fourth and married a fifth, whom he also had beheaded. The sixth outlived him.

As for the emperor Charles V, he had grown weary of his vast empire, with all its troubles and confusion, and the increasingly savage battles fought in the name of religion. He had spent his life fighting: against German princes who were followers of Luther, against the pope, against the kings of both England and France, and against the Turks, who had come from the east in 1453 and had conquered Constantinople, capital of the Roman Empire of the East. They had then gone on to lay waste to Hungary and in 1529 had reached the gates of Vienna, the capital of Austria which they besieged without success.

And having grown tired of his empire, along with its sun that never set, Charles V installed his brother Ferdinand as ruler of Austria and emperor of Germany, and gave Spain and the Netherlands to his son Philip. He then withdrew, in 1556, an old and broken man, to the Spanish monastery of San Geronimo de Yuste. It is said that he spent his time there repairing and regulating all the clocks. He wanted them to chime at the same time. When he didn’t succeed, he is reported to have said: ‘How did I ever presume to try to unite all the peoples of my empire when I cannot, even once, persuade a few clocks to chime together.’ He died lonely and embittered. And as for the clocks of his former empire, whenever they struck the hour, their chimes were further and further apart.

HE

C

HURCH AT

W

AR

But when he was finally restored to health, he didn’t simply go off and fight in one of the many wars that had broken out between Lutherans and Catholics. He took himself to university. There he studied and reflected, and reflected and studied, to prepare himself for the battle he had chosen to undertake. For it seemed clear to him that if you want to conquer others you must first conquer yourself. So with unbelievable severity he worked at mastering himself. Somewhat like the Buddha, but with a different aim in mind. Like the Buddha, Ignatius wished to rid himself of all desires. But rather than seeking release from human suffering here on earth, he wanted to devote himself, body and soul, to the service of the Church. After many years of practice he reached a point at which he could successfully prevent himself from having certain thoughts, or, if he wished, picture something so clearly in his mind that it was as if he saw it there in front of him. His preparation was complete. He demanded no less of his friends. And when they had all achieved the same iron control over their thoughts, they founded an order together called the Society of Jesus. Its members were known as Jesuits.

This little company of select and highly educated men offered itself to the Pope to campaign for the Church, and in 1540 their offer was accepted. Their battle began immediately, with all the strategy and force of a military campaign. The first thing they did was to tackle the abuses that had brought about the conflict with Luther. In a great gathering of the Church held in Trent in the Southern Tirol, which lasted from 1545 to 1563, changes and reforms were agreed that enhanced the power and dignity of the Church. Priests would return to being priests, and not just princes living in splendour. The Church would take better care of the poor. Above all, it would take steps to educate the people. And here the Jesuits, as learned, disciplined and loyal servants of the Church, came into their own. For as teachers they could make their ideas known, not only to the common people, but to the nobility as well through their teaching at universities. Nor was it only through their work as teachers and preachers of the faith in distant lands that their influence spread. In the courts of kings they were frequently employed as confessors. And because they were men of great intelligence and understanding, trained to see into the souls of men, they were well placed to guide and influence the mighty in their decisions.

This movement to re-awaken the piety of old, not through a separation from the Catholic Church, but through the renewal of that Church, and thus to actively challenge the Reformation, is known as the Counter-Reformation. People became very austere and strict during this period of religious warfare. Almost as austere and strict as Ignatius of Loyola himself. The delight Florentines took in their leaders’ magnificence and splendour was over. And once again, what was looked for in a man was piety and readiness to serve the Church. Noblemen stopped wearing bright and ample robes and now looked more like monks in severe, black, close-cut gowns and white ruffs, over which their sombre, unsmiling faces tapered away into little pointed beards. Every nobleman wore a sword on his belt and challenged anyone who insulted his honour to a duel.

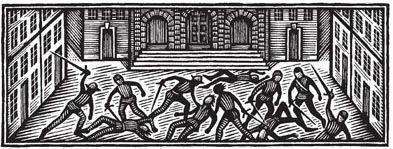

These men, with their careful, measured gestures and their rigid formality, were mostly seasoned warriors, and never more implacable than when fighting for their beliefs. Germany was not the only land riven by strife between Protestant and Catholic princes. The most ferocious wars were fought in France, where Protestants were known as Huguenots. In 1572 the French queen invited all the Huguenot nobility to a wedding at court, and on the eve of St Bartholomew, she had them assassinated. That’s what wars were like in those days.

No one was more stern, more inflexible or more ruthless than the leader of all the Catholics. King Philip II of Spain was the son of the emperor Charles V. His court was formal and austere. Every act was regulated: who had to kneel at the sight of the king and who might wear a hat in his presence. In what order those who dined were to be served at the high table, and in what order the nobles were to enter the church for Mass.

King Philip himself was an unusually conscientious sovereign, who insisted on handling every decision and every letter himself. He worked from dawn to dusk with his advisers, many of whom were monks. His purpose in life as he saw it was to root out all forms of unbelief. In his own country he had thousands of people burned at the stake for heresy – not just Protestants, but Jews and Muslims who had lived there since the time when Spain was under Arab rule. And because he saw himself as Protector and Defender of the Faith, just as the German emperor had before him, he joined forces with a Venetian fleet and attacked the Turks, whose sea power hadn’t stopped growing since their conquest of Constantinople. The allied Christians were victorious, and the Turkish fleet was completely destroyed at Lepanto, in 1571.