A Little History of the World (16 page)

Read A Little History of the World Online

Authors: E. H. Gombrich,Clifford Harper

Shih Huang-ti didn’t have a long reign. Soon a new family ascended the throne of the Son of Heaven. This was the Han family. They saw no need to undo all Shih Huang-ti’s good works, and under their rule China remained strong and unified. But by now the Hans were no longer enemies of history. On the contrary, they remembered China’s debt to the teachings of Confucius and set about searching high and low for all those ancient writings. It turned out that many people had had the courage not to burn them after all. Now they were carefully collected and valued twice as highly as before. And to become a government official, you had to know them all.

China is, in fact, the only country in the world to be ruled for hundreds of years, not by the nobility, nor by soldiers, nor even by the priesthood, but by scholars. No matter where you came from, or whether you were rich or poor, as long as you gained high marks in your exams you could become an official. The highest post went to the person with the highest marks. But the exams were far from easy. You had to be able to write thousands of characters, and you can imagine how hard that is. What is more, you had to know an enormous number of ancient books and all the rules and teachings of Confucius and the other ancient sages off by heart.

So Shih Huang-ti’s burning of the books was all in vain, and if you thought he was right, you were mistaken. It’s a bad idea to try to prevent people from knowing their own history. If you want to do anything new you must first make sure you know what people have tried before.

ULERS OF THE

W

ESTERN

W

ORLD

Provided they did so, they were left more or less in peace. They could practise their own religion and speak their own language, and in many ways they benefited from all the good things the Romans brought, such as roads. Many of these, splendidly paved, led out from Rome across the plains and over distant mountain passes to remote and inaccessible parts of the empire. It must be said that the Romans didn’t build these roads out of consideration for the people living there. On the contrary, their aim was to send news and troops to all parts of the empire in the shortest possible time. The Romans were superb engineers.

Most impressive of all their works were their magnificent aqueducts. These brought water from distant mountains and carried it down through valleys and into the towns – clear, fresh water to fill innumerable fountains and bathhouses – so that Rome’s provincial officials could enjoy all the comforts they were used to having at home.

A Roman citizen living abroad always retained his separate status, for he lived according to Roman law. Wherever he happened to be in that vast empire, he could turn to a Roman official and say: ‘I am a citizen of Rome!’ These words had the effect of a magic formula. If until then no one had paid him much attention, everyone would instantly become polite and obliging.

In those days, however, the true rulers of the world were the Roman soldiers. It was they who held the gigantic empire together, suppressing revolts where necessary and ferociously punishing all who dared oppose them. Courageous, experienced and ambitious, they conquered a new land – to the north, to the south or to the east – almost every decade.

People who saw the tight columns of well-drilled soldiers, marching slowly in their metal-plated tunics, with their shields and javelins, their slings and swords and their catapults for hurling rocks and arrows, knew that it was useless to resist. War was their favourite pastime. After each victory they returned in triumph to Rome, led by their generals, with all their captives and their loot. To the sound of trumpets they would march past the cheering crowds, through gates of honour and triumphal arches. Above their heads they held pictures and placards, like billboards to advertise their victories. The general would stand tall in his chariot, a crown of laurel on his head and wearing the sacred cape worn by the statue of Jupiter, God of Gods, in his temple. Like a second Jupiter, he would climb the steep path to the Capitol, the citadel of Rome. And there in the temple, high above the city, he would make his solemn sacrifice of thanksgiving to that god, while below him the leaders of the vanquished were put to death.

A general who had many such victories, with plenty of booty for his troops and land for them to cultivate when they grew old and were retired from service, was loved by his men like a father. They would give their all for him. Not just on foreign soil but at home as well. For, in their eyes, a great hero of the battlefield was just what was needed to keep order at home, where there was often trouble brewing. For Rome had become a huge city with large numbers of destitute people who had no work and no money. If the provinces failed to send grain it meant famine in Rome.

Two brothers, living in about 130 BC (that is, sixteen years after the destruction of Carthage), thought up a plan to encourage this multitude of poor and starving people to move to Africa and settle there as farmers. These brothers were the Gracchi. But they were both killed in the course of political struggles.

The same blind devotion that the soldiers gave their general went to any man who gave grain to the multitudes and put on splendid festivals. For Romans loved festivals. But these were not at all like those of the Greeks, where leading citizens took part in sporting contests and sang hymns in honour of the Father of the Gods. These would have seemed ridiculous to any Roman. What serious, self-respecting man would sing in public, or take off his formal, many-pleated toga to throw javelins before an audience? Such things were best left to captives. It was they who had to wrestle and fight, confront wild beasts and stage whole battles in the arena under the eyes of thousands – sometimes tens of thousands – of spectators. It all got very serious and bloody, but that was just what made it so exciting for the Romans. Especially when, instead of trained professionals, men who had been condemned to death were thrown into the arena to grapple with lions, bears, tigers and even elephants.

Anyone who put on shows like these, with generous handouts of grain, was loved by the crowd and could do what he pleased. As you can imagine, many tried. If two rivals fought for power, one might have the army and the patricians on his side while the other had the support of the plebeians and poor peasants. And in a long drawn-out struggle, now one and now the other would be uppermost. There were two such famous enemies called Marius and Sulla. Marius had been fighting in Africa and, several years later, took his army to rescue the Roman empire when it was in peril. In 113 BC, barbarians from the north had invaded Italy (as the Dorians had Greece or, seven hundred years later, the Gauls had Rome). These invaders were the Cimbri and the Teutones, ancestors of today’s Germans. They had fought so bravely that they had actually succeeded in putting the Roman legions to flight. But Marius and his army had been able to halt and defeat them.

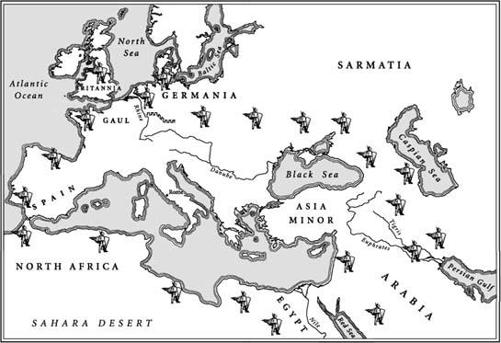

Legionaries kept watch along all the frontiers of the vast Roman empire. They also built a palisade that stretched from the Rhine to the Danube.

This made him the most celebrated man in Rome. But in the meantime, Sulla had fought on in Africa, and he too had returned triumphant. Both men got ready to fight it out. Marius had all Sulla’s friends killed. Sulla in his turn made a long list of the Romans who supported Marius and had them murdered. He then generously presented all their property to the state. After which he and his soldiers ruled the Roman empire till 79

BC

.

In the course of these turbulent times, Romans had changed a great deal. All the peasants had gone. A handful of rich people had bought up the smaller farms and brought in slaves to run their vast estates. Romans had, in fact, grown used to leaving everything to be managed by slaves. Not only those who worked in the mines and quarries, but even the tutors of patrician children were mostly slaves, prisoners of war or their descendants. They were treated as goods, bought and sold like cattle. Slave owners could do what they liked with their slaves – even kill them. Slaves had no rights at all. Some masters sold them to fight with wild beasts in the arena, where they were known as gladiators. On one occasion the gladiators rebelled against this treatment. They were urged on by a slave called Spartacus, and many slaves from the country estates rallied to him. They fought with a ferocity born of desperation and the Romans were hard put to suppress the revolt, for which the slaves paid a terrible price. That was in 71

BC

.

By this time new generals had become the darlings of the Roman populace. The most popular of them all was Gaius Julius Caesar. He too knew how to win the hearts of the masses, and had raised colossal sums of money for magnificent festivals and gifts of grain. But more than that, he was a truly great general, one of the greatest there has ever been. One day he went to war. A few days later, Rome received a letter from him with just these three Latin words:

veni, vidi, vici

– meaning ‘I came, I saw, I conquered.’ That is how fast he worked!

He conquered France – in those days known as Gaul – and made it a province of Rome. This was no small feat, for the peoples who lived there were exceptionally brave and warlike, and not easily intimidated. The conquest took seven years, from 58 to 51 BC. He fought against the Helvetii (who lived in what is now Switzerland), the Gauls and the Germans. Twice he crossed the Rhine into land that is now part of Germany and twice he crossed the sea to England, known to the Romans as Britannia. He did this to teach the neighbouring tribes a proper fear and respect for Rome. Although the Gauls continued to fight desperately, for years on end, he attacked them repeatedly, and everywhere he went he left troops in control behind him. Once Gaul had become a Roman province the inhabitants soon learnt to speak Latin, just as they had in Spain. And this is why French and Spanish, which come from the language of the Romans, are known as Romance languages.

After the conquest of Gaul, Caesar turned his army towards Italy. He was now the most powerful man in the world. Other generals who had previously been his allies he attacked and defeated. And after he had seduced Cleopatra, the beautiful queen of Egypt, he was able to add Egypt to the Roman empire. Then he set about putting it in order. For this he was ideally suited, for he had an exceptionally orderly mind. He was able to dictate two letters at the same time without getting his thoughts in a tangle. Imagine that!