A Kind of Grace (15 page)

My parents' marriage was rocky, and for several years after my mother died, I was angry with my father. But we eventually reconciled.

PHOTO BY TONY DUFFY/COURTESY OF ALLSPORT

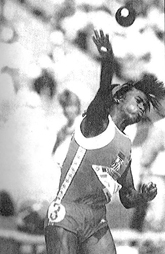

My joy over winning the heptathlon gold medal and setting a world record at the 1988 Olympics was quickly shattered by speculation that I used performance-enhancing drugs.

PHOTO BY TONY DUFFY/COURTESY OF ALLSPORT

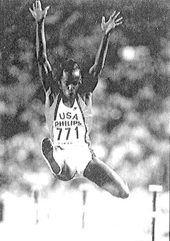

I got off to a flying start during the long jump at the 1991 World Championships …

PHOTO BY TONY DUFFY/COURTESY OF ALLSPORT

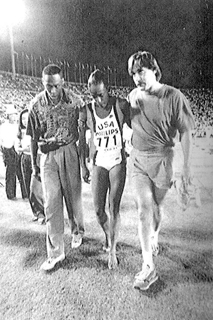

… But I was nagged by ailments. Al and Bob Forster, my physical therapist, had to help me walk off the field because I twisted my ankle en route to winning.

PHOTO BY TONY DUFFY/COURTESY OF ALLSPORT

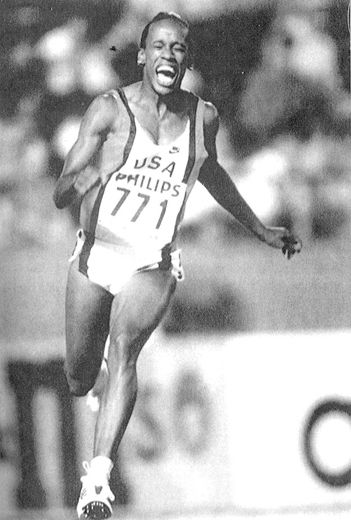

Eventually, an injury did me in at the 1991 Worlds. I was forced to withdraw from the heptathlon after pulling my hamstring during the 200 meters.

PHOTO BY TONY DUFFY/COURTESY OF ALLSPORT

For too many years, I didn't take my asthma condition seriously. But by 1995 I'd learned my lesson. As much as I hated wearing this breathing mask during the 800 meters at the U.S. Championships, I also knew the pollen in the air that day could trigger a fatal attack if I didn't.

PHOTO BY KIRBY LEE/THE SPORTING IMAGE

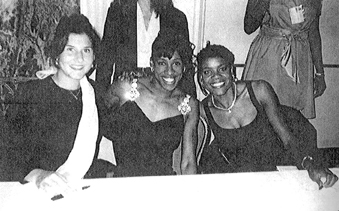

Monica Seles and I have been through a lot together since she hired Bobby to improve her strength and conditioning in 1993. I consoled her while she recovered from being stabbed, and she was with me and Bobby the night I almost died during an asthma attack. Here we are, healthy and happy, in 1995 with Sheryl Swoopes at a Women's Sports Foundation dinner.

COURTESY OF VALARIE FOSTER

What was meningitis? It sounded so gruesome. How could it have overtaken her so fast? Had someone made a mistake? Had she suffered? Had she said anything? I kept imagining her in the ambulance and then in the hospital bed. The picture wouldn't leave my mind. It tormented me.

My racing thoughts turned to the rest of my family. Della sounded awful. How was Al taking the news? I should have called him, but I didn't think of it. How were Angie and Debra coping? Were they with Momma when it happened? Where was Daddy? What was going to happen to us now?

Mostly, I wondered why this had happened to my mother, after all she'd been through in her life. Was God punishing me by taking her away? I replayed in my head that conversation with her about not coming home for Christmas. She was so sad about my not coming home. If I could just go back in time … make a different choice. I should have followed my heart and gone home. But no, I had to act like I was so strong, pretending not to be homesick.

Endlessly, I berated myself for making the decision I had. I'd missed out on Christmas and forfeited the opportunity to be with my mother one last time, all because I'd been too proud. Now, she was unconscious, hanging to life by the thinnest of threads. An overpowering sense of regret washed over me. I'd never been so sad and so sorry about anything.

The sun was setting as the plane touched down at Lambert Field, the St. Louis airport. It was about 5:30 in the afternoon when my aunt Marcella greeted me at the gate. She was dabbing away her tears with a tissue.

As we drove to East St. Louis, I stared blankly out the window into the distance. Cars, buildings and road signs whizzed past, but I noticed none of it. I was lost in my sorrow.

The temperature outside was right around freezing when we stepped out of the car at the hospital parking lot. An ache burned inside my stomach. As we rushed through the sliding glass door and entered the hospital, my throat and eyes started burning as well. I wanted to go straight to Momma's side. But Joyce wanted to talk to me first.

The despair was palpable as the elevator doors opened to the fourth floor. Most of the nurses and orderlies who worked with my mother had gathered on the floor after their shifts ended at 3:00 that afternoon to hold a vigil. Marcella walked beside me and put her arm around my shoulder as we greeted Eva Wren, Helen Sandkuhl, Eula McKinley and Eula Royer and the rest of Momma's friends on our way to a small room at the end of the hall. Although there were dozens of people standing around the nurses' stations and milling around the hallways, it was strangely quiet on the floor. Everyone was still dressed in their white, green and blue hospital uniforms. They all wore name badges and sad expressions. Most of them looked just like I felt: grief-stricken and dazed.

It was the same way in the crowded room at the end of the hallway where the rest of the family was waiting. As I walked in, I forced a smile to my lips. I don't know why I thought it was necessary to smile. I couldn't keep it up for long. The first face I saw was Al's. He'd been at a track meet when he got the news. Della, Al, Debra and Angie ran to me. We hugged and cried. I also hugged my mother's uncles, Albert and Joseph Rainey. Everyone had bloodshot eyes from crying all day. Daddy was there, too. Rev. Owens was consoling us when Momma's doctor, Dr. Rene Julien, and Joyce came into the room. Joyce walked over to the couch and stood beside us. Her eyes were red but she was completely composed.

“What happened? When can I see Momma?” I said.

“Your mother developed a really bad bacterial infection,” Dr. Julien said. “We think it was meningitis, but we're not positive.”

Dr. Julien said she started running a very high fever as the bacteria infected her and quickly spread throughout her body. She'd experienced a lot of bleeding internally and externally and it had caused swelling all over her body. He told us she was on a respirator, which was keeping her body alive. “She's suffered irreversible brain damage,” Dr. Julien said. “Her body is still functioning, but essentially, she's dead. I'm really sorry. There was nothing we could do.”

Joyce looked at all of us. “When you go in to see her you'll see that she has a pulse. But the machines she's connected to are the things keeping her body going. Mary can't do it for herself because her brain is dead.”

I'd been nurturing the irrational hope that my mother had a chance to recover. But Joyce's and Dr. Julien's words foreclosed any possibility that we'd all wake up from this nightmare and Momma would be alive again. For everyone standing there, Joyce's words were like the irrevocable locking of a door. The Mary Joyner we all knew—my mother, and my life's greatest inspiration—was gone.

Angie and Debra, sitting on opposite sides of Al, burst into tears and collapsed into his arms. They were completely consumed with grief. I just wanted to see my mother's face one last time.

“Can I see her?” I asked.

“Yes, but first I need to prepare you for what you're going to see when you go in the room,” Joyce said.

I couldn't take much more of it. The bad news just wouldn't end.

“Your mother doesn't look the way you remember her. The bleeding caused her skin color to change and made her body swell. It also made her skin very fragile. You'll have to be careful if you touch her because in her condition, the skin ruptures easily. This is a horrible, horrible disease.”

Dr. Julien explained that her disease, whatever it was, was probably highly contagious. Momma was isolated from other patients. Anyone who came in contact with her had to wear protective clothing and had to take an antibiotic pill.

Al and I went in together. The protective gear made us look like we were ready to assist in surgery. A white shower cap covered my head. I pulled on the baggy white pants over my jeans and tied on a long white gown over my sweater. I covered my shoes with white footies and my hands with white plastic gloves. After swallowing the pill, I closed my eyes, took a long, deep breath and walked with Joyce and Al to Momma's room.

Though she'd tried, Joyce could never have prepared me for what I saw when I walked into my mother's room. When I saw Momma, I was devastated. My knees buckled. Joyce and Al caught me as I collapsed into a heap of tears and sobs.

The person lying in that hospital bed looked nothing like the beautiful smiling woman in the picture on my desk. The disease had ravaged her. She looked as if she'd gained 100 pounds. Her now-swollen head was the size of a big honeydew melon. Her lovely face was stretched out of proportion and the caramel-colored skin on her face, neck and hands had turned as black as licorice. Her nose was packed with white gauze. Her eyes were shut. She looked as if she was in a deep, deep sleep.