A History of Zionism (9 page)

Read A History of Zionism Online

Authors: Walter Laqueur

Tags: #History, #Israel, #Jewish Studies, #Social History, #20th Century, #Sociology & Anthropology: Professional, #c 1700 to c 1800, #Middle East, #Nationalism, #Sociology, #Jewish, #Palestine, #History of specific racial & ethnic groups, #Political Science, #Social Science, #c 1800 to c 1900, #Zionism, #Political Ideologies, #Social & cultural history

The optimism of the early emancipation period had petered out by 1880 as unforeseen tensions and conflicts appeared, causing occasional pessimism and heart-searching. But only very few Jews accepted the argument of the racial antisemites that they could never be assimilated and had therefore to be ejected from the body politic of the host people. No one anticipated a relapse into barbarism, and most Jews continued their struggle for full civic rights as patriotic citizens of their respective countries of birth. A retreat from assimilation seemed altogether unthinkable, though perhaps its ultimate goals had to be redefined, perhaps the process of integration would take much longer than had been commonly believed. The rebirth of nationalist and racialist doctrines in Europe after 1870 should have been a warning, but there were a great many problems and conflicts besetting the European nations at that time and the Jewish question seemed by no means the most intricate or the least tractable. As far as western Jewry was concerned, assimilation had proceeded very far and an alternative solution seemed to most of them neither desirable nor, indeed, possible.

*

According to the available evidence there were in fact fewer Jewish conversions during the nineteenth century in Germany than in England, and much fewer than in Russia and Austria-Hungary. De la Roi,

Judentaufen im 19. Jahrhundert

, Berlin, 1900.

*

A statement like this makes strange reading in the light of the Hitlerian experience. Yet for all that it was essentially correct. The affinity between Germanism and Judaism was felt and expressed not only by assimilationists but also by many ardent Zionists. ‘No culture had such a decisive impact on the Jews as the German’, Nahum Goldmann wrote in 1916, in a pamphlet in which he maintained that in many ways the Zionists were much closer to the German national spirit than the assimilationists, who had received their inspiration from the liberal thinkers of Britain and France. ‘The young national Jewish movement, on the other hand, had made the national idea the central concept of its philosophy: Fichte, Hegel, Lagarde

(sic)

and the other leading spirits of the German national idea - they were also our teachers. It was no accident that Theodor Herzl, the genius who founded modern political Zionism, came from German culture to the Jewish national idea.’ (Nahum Goldmann:

Von der weltkulturellen Bedeutung und Aufgabe des Judentums

, Munich, 1916.) Writing in the middle of the First World War, Goldmann, in a series of propaganda leaflets, overstated his case, and it is not difficult to misconstrue statements of this kind. But there is no denying that German philosophy of the nineteenth century was a source of inspiration to modern political ideologies from the extreme left to the extreme right all over Europe, and Zionism was no exception.

*

Working for the Germans during the Second World War, this

homme de lettres

wrote to a friend from Hamburg in September 1943 that he ‘adored this country and its national character. … The people here have a smile on their faces the like of which one does not see anywhere else in the west.’

2

THE FORERUNNERS

Zionism, according to a recent encyclopaedia, is a worldwide political movement launched by Theodor Herzl in 1897. Equally it might be said that Socialism was founded in 1848 by Karl Marx. It is clearly difficult to do justice to the origins of a movement of any consequence in a one-sentence definition. The Jewish national revival which took place in the nineteenth century, culminating in political Zionism, was preceded by a great many activities and publications, by countless projects, declarations and meetings; thousands of Jews had in fact settled in Palestine before Herzl ever thought of a Jewish state. These activities took place in various countries and on different levels; it is difficult to classify them and almost impossible to find a common denominator for them. They include projects of British and French statesmen to establish a Jewish state; manifestos issued by obscure east European rabbis; the publication of romantic novels by non-Jewish writers; associations to promote settlement in Palestine, and to spread Jewish culture and national consciousness. The term Zionism appeared only in the 1890s,

*

but the cause, the concept of Zion, has been present throughout Jewish history.

A survey of the origins of Zionism must take as its starting point the central place of Zion in the thoughts, the prayers, and the dreams of the Jews in their dispersion. The blessing ‘Next year in Jerusalem’ is part of the Jewish ritual and many generations of practising Jews have turned towards the east when saying the

Shemone Essre

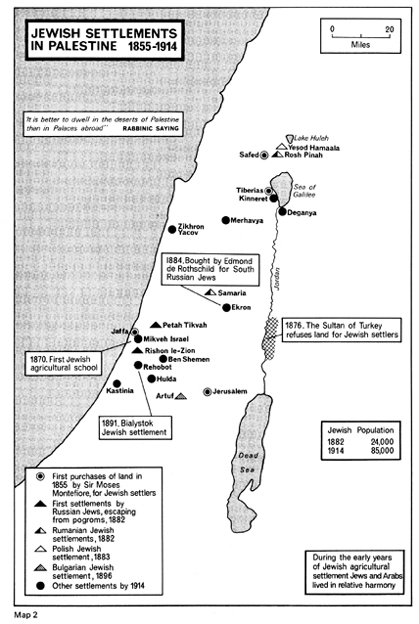

, the central prayer in the Jewish liturgy. The longing for Zion manifested itself in the appearance of many messiahs, from David Alroy in the twelfth century to Shabtai Zvi in the seventeenth, in the poems of Yehuda Halevy, in the meditations of generations of mystics. Physical contact between the Jews and their former homeland was never completely broken; throughout the Middle Ages sizable Jewish communities existed in Jerusalem and Safed, and smaller ones in Nablus and Hebron. Attempts by Don Yosef Nasi, Duke of Naxos, to promote Jewish colonisation near Tiberias failed, but individual migration to Palestine never ceased; it reached a new height with the arrival of groups of Hassidim in the late eighteenth century.

Memoranda and pamphlets proposing the restoration of the Jews to their ancient homeland abounded in England in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. During his Egyptian campaign Napoleon published a proclamation calling the Jews of Asia and Africa to join him in restoring the old Jerusalem. Colonel Pestel, the leader of the first Russian revolutionary movement, the Decembrists, suggested in his programme the establishment of a Jewish state in Asia Minor. Even earlier, in 1797, Prince Charles de Ligne developed the same idea in a private memorandum, and Manuel Noah, an American-Jewish judge, writer and former diplomat, proposed the establishment of a token Jewish state (Ararat) on Grand Island near Buffalo. Beginning with the 1840s, Jewish newspapers frequently discussed the return to Palestine as a laudable though obviously impractical scheme; with the progress of assimilation there seemed to be less readiness to entertain projects for which there was obviously no urgent need. Elderly Jews still went to Jerusalem to die, the Jewish communities in Palestine still sent their emissaries on yearly begging tours to their co-religionists in Europe. These missions never failed to evoke some response, but at the same time they impressed only too clearly on European Jews the depth of the misery and degradation of their brethren in the Holy Land. For centuries under Turkish rule, later on a bone of contention between the khedives of Egypt and the sultan in Constantinople, administered - to use a blatant euphemism - by often cruel and mostly inefficient Turkish pashas, the country was in a state of utter decay. It did not even have an administrative identity, for Palestine had become part of the Damascus district. The situation in the Holy Land reflected the decline that had overtaken the Ottoman empire since its heyday in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries. This desolate province seemed an unlikely haven for Jews from Europe, however poor and backward. But it was precisely as a result of the weakness of the Ottoman empire that the issue of a Jewish state was again raised towards the middle of the nineteenth century. The Eastern Question, the sickness and possible demise of the Ottoman empire, was widely discussed in the chanceries of Europe. Between 1839 and 1854, as interest in Palestine grew, all the major European powers and the United States established consulates in Jerusalem. In 1839 the London

Globe

published a series of articles advocating the establishment of an independent state in Syria and Palestine, envisaging the mass settlement of Jews. The

Globe

was a mouthpiece of the Foreign Office and the project was known to have Palmerston’s support. The author of this series, as another writer in

The Times

pointed out (17 August 1840), did not assume that the masses of European Jews would immediately migrate to Syria, but he thought that a concentration of oriental Jews in Palestine was by no means an unreal vision: the European Jews had the money to buy (or lease) the country from the sultan, and the five big powers would provide a guarantee for the new state. Some of these policy planners were in favour of an independent monarchy, others of a republic, but all were convinced that with England taking the initiative in returning the Jews to Palestine, like Cyrus in antiquity, a sufficient number of them would settle to make the project a going concern. The fact that a Jewish state would constitute a buffer between the Turks and the Egyptians and enhance British influence in the Levant was a consideration which no doubt played its part, but political, military, and economic interests alone hardly suffice to explain the strong support given by many public figures for the idea of a Jewish state. England had other opportunities in the Near East and the Jewish option was by no means the most obvious or promising. The enthusiasm of Colonel Henry Churchill, a former consul in Damascus, and other ardent protagonists of the idea, can be understood only against the background of the deep-rooted biblical tradition in Britain, and the belief that it was Britian’s historical mission to lead the suffering Jews back to their homeland.

There was a strong romantic element in all these visions, a mood which also found expression in some of Disraeli’s novels. ‘You ask me what I wish’, he wrote in

Alroy

; ‘my answer is “Jerusalem, all we have forfeited, all we have yearned after, all for which we have fought”.’ In

Coningsby

and

Tancred

, the story of the son of a duke who goes to Palestine to study the ‘Asiatic problem’, Disraeli returned to the same topic. The vicissitudes of history found their explanation in the fact that ‘all is race’; the Jews were essentially a strong, a superior race; given the right leadership there was nothing they would not be able to achieve. Disraeli’s novels, published in the 1840s and 1850s, were full of mysterious hints, lacking a clear focus. George Eliot’s

Daniel Deronda

, on the other hand, which appeared in 1876, was a novel with a specific Zionist programme. Daniel Deronda (the ‘most irresistible man in the literature of fiction’ according to Henry James) decides to devote his life to the cause of a national centre for the Jews. The figure of Mordechai Cohen, Deronda’s mentor, is there to show that Judaism is still alive, that it is on as high a level as Christianity, and that the Jews still have a mission to fulfil - the repossession of Palestine.

The Jewish reaction to these noble visions by well-meaning non-Jews and lapsed Jews was on the whole lukewarm. Ludwig Philippson, the editor of the leading periodical of German Jewry, wrote

*

that it was only too easy to understand that some young Jews, having to face antisemitism everywhere, were tired of the fruitless struggle and wanted a little place on the earth all their own, where they could find complete recognition as human beings. But Palestine was an unlikely and unpromising place for any such endeavour; a Jewish state dependent on the mercy of an oriental potentate and the protection of remote powers would be the plaything of stronger forces. There was a real danger that it would perish - many other states situated on these dangerous cross-roads of Europe, Asia, and Africa had been destroyed throughout history. What kind of freedom, what level of material existence could Jews expect in that forsaken land? What had a movement of this kind in common with their messianic hopes? Anglo-Jewry did not engage in open polemics against the visions of these well-meaning but obviously eccentric compatriots; its members acknowledged them gratefully, promised support if someone else would take the initiative, and shelved the whole idea. Nor did east European Jewry at the time take much notice.

The British had no monopoly of blueprints of this kind; several Jewish writers on the continent were also advancing similar projects at the same time. They usually entered into surprising detail but it was no doubt in anticipation of a hostile reception that most of them were published anonymously. One of these projects,

Neujudäa

,

†

published in Berlin in 1840, accepted the idea of a Jewish state but for practical reasons rejected Palestine, which ‘had been the cradle of the Jewish people but could not be its permanent home’. It suggested the American middle west, Arkansas or Oregon; ten million dollars would be sufficient to induce the American Government to put at the disposal of the Jews an area the size of France. There was every reason to hurry with the realisation of the plan, for in the near future the Americas and even Australia would be settled by newcomers and then it would be too late. The unknown author believed that such an opportunity should not be allowed to pass: antisemitism was endemic in Europe, it would not diminish, and the Jews were condemned to lead a parasitic existence among peoples who hated them. In America, on the other hand, they had the opportunity to demonstrate their real ability. An agency on the pattern of the East Indian Company should be founded to establish an ‘aristocratic’ republic in which only Jews would be citizens. In brief, America, as far as a Jewish state was concerned, as in other respects, was the country of unlimited possibilities.

Another anonymous project published a few months later is remarkable because of its acute analysis of the sources of the Jewish problem: the writer was convinced that emancipation had by no means solved the Jewish question: Jews were at best suffered, nowhere were they welcome or loved. For the Jews

were

strangers; there was a world of difference in body and soul between the semitic

Urstamm

and those whose ancestors lived in northern Europe. The Jews were neither Germans nor Slavs, neither French nor Greek, but the children of Israel, related to the Arabs. The writer called for an early return to Palestine; the sultan and Mehemet Ali could be persuaded to protect the Jews; the main obstacle was the passivity of the Jews themselves. The Serbs and the Greeks had won a great deal of outside support in their struggle for national liberation. It should not be impossible to find a major government to support the establishment of a base of humanism and progress in anarchy-torn Syria.

*

This project had a mixed reception; its supporters argued that a neutral Jewish state between the Nile, Euphrates, and Taurus could restore equilibrium among the powers in the east; it would help Turkey against Mehemet Ali. Elsewhere there was scepticism with regard to the intentions of the European powers; would they really want to play the role of a Messiah, or was it not more likely that they were simply pursuing their great-power ambitions? Was not hostility towards Catholicism and France the main motive behind the plan in favour of a Jewish state recently submitted to the Protestant monarchs, rather than a genuine humanitarian desire to help the Jews? It was generally acknowledged that there was in Britain sincere sympathy for the restoration of Israel, and that this coincided with its imperial interests, but as one of the leaders of German Jewry declared: for us Germans the orient is simply too remote; perhaps our British co-religionists are cleverer than we are.

The projects of the 1840s showed a great deal of ingenuity, acute analysis, and sometimes a remarkable gift of prophecy. But in the last resort they were all romantic and artificial constructions suspended in mid-air; they did not provide an answer to one all-important question: who would carry out these projects, who would lead the Jews in their return to their homeland? The anonymity of the authors made it clear that they were not volunteering for this mission.

The spate of projects at this time was a direct outcome of the acute crisis in the Near East, the beginning of the dissolution of the Ottoman empire. But they did not coincide with any marked rise in Jewish national awareness. Despite all the setbacks on the road to emancipation, the overwhelming majority of western Jews were by no means willing to abandon that goal. The idea of settling in an uncivilised, backward country, subject to the whims of arbitrary and cruel Turkish pashas, was unlikely to appeal to them. The various plans were not devoid of political vision, but the link between the dream and its realisation was missing, and for that reason, in the last resort, they were bound to have no effect. They were premature, just as the ideas of the Utopian Socialists had no lasting impact because they were propagated in a vacuum, without reference to the political and social forces which could provide leadership in the struggle for their realisation. Even Moses Hess’

Rome and Jerusalem

, the most important by far of these appeals, belongs to this genre. Published in 1862, it had no immediate effect. Isaiah Berlin, who compared it to a bombshell, exaggerated its impact; 160 copies of the book had been sold one year after publication and soon after that the publisher suggested that Hess ought to buy back the remainder at a reduced price. When Herzl wrote his

Judenstaat

more than thirty years later, he had not even heard of it. And yet

Rome and Jerusalem

stands out in the literature of the time for reasons that will be immediately obvious.