A History of the Crusades-Vol 1 (27 page)

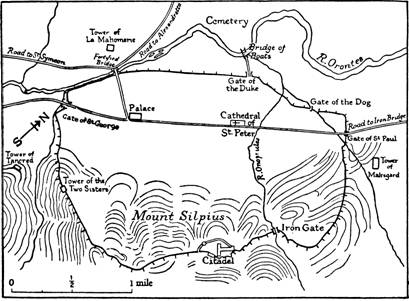

Plan of Antioch

in 1098

Yaghi-Siyan s

Search for Allies

The news of the Christian advance alarmed

Yaghi-Siyan. Antioch was the acknowledged objective of the Crusaders; and,

indeed, they could not hope to be able to march southward towards Palestine

unless the great fortress was in their hands. Yaghi-Siyan’s subjects were most

of them Christians, Greeks, Armenians and Syrians. The Syrian Christians,

hating Greeks and Armenians alike, might remain loyal; but he could not trust

the others. Hitherto it seems that he was tolerant towards the Christians. The

Orthodox Patriarch, John the Oxite, was permitted to reside in the city, whose

great churches had not been turned into mosques. But with the approach of the

Crusade he began restrictive measures. The Patriarch, the head of the most

important community in Antioch, was thrown into prison. Many leading Christians

were ejected from the city; others fled. The Cathedral of St Peter was

desecrated and became a stable for the Emir’s horses. Some persecution was

carried on in the villages outside the city; which had for a result the prompt

massacre of the Turkish garrisons by the villagers as soon as the Crusaders

were at hand.

Next Yaghi-Siyan searched for allies. Ridwan of

Aleppo would do nothing to help him, in short-sighted revenge for his treachery

the previous year. But Duqaq of Damascus, to whom Yaghi-Siyan’s son, Shams

ad-Daula, had gone personally to appeal, prepared an expedition for his rescue;

and his

atabeg

, the Turcoman Toghtekin, and the Emir Janah ad-Daula of

Homs, offered their support. Another envoy went to the court of Kerbogha,

atabeg

of Mosul. Kerbogha was now the leading prince in upper Mesopotamia and the

Jezireh. He was wise enough to see the threat of the Crusade to the whole

Moslem world; and he had long had his eye on Aleppo. If he could acquire

Antioch, Ridwan would be encircled and in his power. He, too, prepared an army

to rescue the city; and, behind him, the Sultans of Baghdad and Persia promised

support. Meanwhile Yaghi-Siyan collected his own considerable forces within the

fortress and began to supply it with provisions against a long blockade.

The Crusaders entered Yaghi-Siyan’s territory

at the small town of Marata, the Turkish garrison fleeing at their approach.

From Marata a detachment under Robert of Flanders went off to the south-west to

liberate the town of Artah, whose Christian population had massacred the

garrison. Meanwhile, on 20 October, the main army reached the Orontes at the

Iron Bridge, where the roads from Marash and Aleppo united to cross the river.

The bridge was heavily fortified, with two towers flanking its entrance. But

the Crusaders attacked it at once, the Bishop of Le Puy directing the

operations, and after a sharp struggle forced their way across. The victory

enabled them to capture a huge convoy of cattle, sheep and com on its way to

provision Yaghi-Siyan’s army. The road now lay open to Antioch, whose citadel

they could see in the distance. Next day Bohemond at the head of the vanguard

arrived before the city walls; and the whole army followed close behind.

The Camps Before

Antioch

The Crusaders were filled with awe at the sight

of the great city. The houses and bazaars of Antioch covered a plain nearly

three miles long and a mile deep between the Orontes and Mount Silpius; and the

villas and palaces of the wealthy dotted the hillside. Round it all rose the

huge fortifications constructed by Justinian and repaired only a century ago by

the Byzantines with the latest devices of their technical skill. To the north

the walls rose out of the low marshy ground along the river, but to the east

and west they climbed steeply up the slopes of the mountain, and to the south

they ran along the summit of the ridge, carried audaciously across the chasm

through which the torrent called Onopnicles broke its way into the plain, and

over a narrow postern called the Iron Gate, and culminated in the superb

citadel a thousand feet above the town. Four hundred towers rose from them,

spaced so as to bring every yard of them within bowshot. At the north-east

comer the Gate of St Paul admitted the road from the Iron Bridge and Aleppo. At

the north-west comer the Gate of St George admitted the road from Lattakieh and

the Lebanese coast. The roads to Alexandretta and the port of St Symeon, the

modem Suadiye, left the city through a great gate on the river-bank and across

a fortified bridge. Smaller gates, the Gate of the Duke and the Gate of the

Dog, led to the river further to the east. Inside the enceinte water was

abundant; there were market-gardens and rough pasture ground for flocks. A

whole army could be housed there and provisioned against a long siege. Nor was

it possible entirely to surround the city; for no troops could be stationed on

the wild precipitous terrain to the south.

It was only through treachery that the Turks

had taken Antioch in 1085; and treachery was the only danger that Yaghi-Siyan

had to face. But he was nervous. If the Crusaders were not able to encircle the

city, he on his side had not enough soldiers to man all its walls. Till

reinforcements came up he could not risk losing any of his men. He made no

attempt to attack the Crusaders as they moved up into position, and for a

fortnight he left them unmolested.

On their arrival the Crusaders installed

themselves outside the north-east comer of the walls. Bohemond occupied the

sector opposite the Gate of St Paul, Raymond that opposite the Gate of the Dog,

with Godfrey on his right, opposite the Gate of the Duke. The remaining armies

waited behind Bohemond, ready to move up where they might be required. The

Bridge Gate and the Gate of St George were for the moment left uncovered. But

work was at once started on a bridge of boats to cross the river from Godfrey’s

camp to the village of Talenki, where the Moslem cemetery lay. This bridge

enabled the army to reach the roads to Alexandretta and St Symeon; and a camp

was soon established on the north of the river.

Yaghi-Siyan had expected an immediate assault

on the city. But, amongst the Crusading leaders, only Raymond advised that they

should try to storm the walls. God, he said, who had protected them so far,

would surely give them the victory. His faith was not shared by the others. The

fortifications daunted them; their troops were tired; they could not afford

heavy losses now. Moreover, if they delayed, reinforcements would join them.

Tancred was due to arrive from Alexandretta. Perhaps the Emperor would soon

come with his admirable siege engines. Guynemer’s fleet might spare them men;

and there were rumours of a Genoese fleet in the offing. Bohemond, whose

counsel carried most weight among them, had his private reasons for opposing

Raymond’s suggestion. His ambitions were now centred on the possession of

Antioch for himself. Not only would he prefer not to see it looted by the

rapacity of an army eager for the pleasure of looting a rich city; but, more

seriously, he feared that were it captured by the united effort of the Crusade

he could never establish an exclusive claim to it. He had learnt the lesson

taught by Alexius at Nicaea. If he could arrange for its surrender to himself,

his title would be far harder to dispute. In a little time he should be able to

make such an arrangement; for he had some knowledge of Oriental methods of

treachery. Under his influence Raymond’s advice was ignored; Raymond’s hatred

of him grew greater; and the one chance of quickly capturing Antioch was lost.

For, had the first attack met with any success, Yaghi-Siyan, whose nerve was

shaking, would have put up a poor resistance. The delay restored his

confidence.

Food Supplies

Begin to Run Out

Bohemond and his friends had no difficulty in

finding intermediaries through whom they could make connections with the enemy.

The Christian refugees and exiles from the city kept close touch with their

relatives within the walls, owing to the gaps in both blockade and the defence.

The Crusaders were well informed of all that passed inside Antioch. But the

system worked both ways; for many of the local Christians, in particular the

Syrians, doubted whether Byzantine or Frankish rule was preferable to Turkish. They

were prepared to ingratiate themselves with Yaghi-Siyan by keeping him equally

well informed of all that went on in the Crusaders’ camp. From them he learnt

of the Crusaders’ reluctance to attack. He began to organize sorties. His men

would creep out from the western gate and cut off any small band of foraging

Franks that they could find separated from the army. He communicated with his

garrison out at Harenc, across the Iron Bridge on the road to Aleppo, and

encouraged it to harass the Franks in the rear. Meanwhile he heard that his son’s

mission to Damascus had succeeded and that an army was coming to relieve him.

As autumn turned to winter, the Crusaders, who

had been unduly cheered by Yaghi-Siyan’s preliminary inaction, began to lose

heart, despite some minor successes. In the middle of November an expedition

led by Bohemond managed to lure the garrison of Harenc from their fortress and

to exterminate it completely. Almost the same day a Genoese squadron of

thirteen vessels appeared at the port of St Symeon, which the Crusaders were

thereupon able to occupy. It brought reinforcements in men and armaments, in

belated response to Pope Urban’s appeal to the city of Genoa, made nearly two

years before. Its arrival gave the Crusaders the comfortable knowledge that

they now could communicate by sea with their homes. But these successes were

overshadowed by the problem of feeding the army. When the Crusaders had first

entered the plain of Antioch, they had found it full of provisions. Sheep and

cattle were plentiful, and the village granaries still contained most of the

year’s harvest. They had fed well and neglected to lay in supplies for the

winter months. Troops were now obliged to go foraging over an ever larger

radius, and were all the more liable to be cut off by Turks coming down from

the mountains. It was soon discovered that the raiders from Antioch would creep

through the gorge of the Onopnicles and wait on the hill above Bohemond’s camp

to attack stragglers returning late to their quarters. To counter this, the

leaders decided to build a fortified tower on the hill, which each of them

guaranteed to garrison in turn. The tower was soon constructed and named

Malregard.

About Christmas time 1097, the army’s stocks of

food were almost exhausted; and there was nothing more to be obtained in the

neighbouring countryside. The princes held a council at which it was decided

that a portion of the army should be sent under Bohemond and Robert of Flanders

up the Orontes valley towards Hama, to raid the villages there and carry off

all the provisions on which they could lay hands. The conduct of the siege

should be meantime left in the hands of Raymond and the Bishop of Le Puy. Godfrey

at the time was seriously ill. Bohemond and Robert set out on 28 December,

taking with them some twenty thousand men. Their departure was at once known to

Yaghi-Siyan. He waited till they were well away, then, on the night of the

29th, made a sortie in strength across the bridge and fell on the Crusaders

encamped north of the river. These were probably Raymond’s troops, who had

moved from their first station when the winter rains made the low ground

between the river and the walls no longer habitable. The attack was unexpected;

but Raymond’s alertness saved the situation. He hastily collected a group of

knights and charged out of the darkness on the Turks; who turned and fled back

across the bridge. So hotly did Raymond pursue them that for a moment his men

obtained a foothold across the bridge before the gates could be swung shut. It

seemed that Raymond was about to justify his belief that the city could be

stormed, when a horse that had thrown its rider suddenly bolted back, pushing

the knights crowded on the bridge into confusion. It was too dark to see what

was happening; and a panic arose among the Crusaders. In their turn they fled,

pursued by the Turks, till they rallied at their camp by the bridge of boats;

and the Turks returned to the city. Many lives were lost on both sides, but

especially among the Frankish knights, whom the Crusade ill could spare. Among

them was Adhemar’s own standard-bearer.

Famine

Meantime Bohemond was riding with Robert of

Flanders southward, totally ignorant of how nearly Antioch had fallen to his

rival, Raymond, and ignorant, too, that a great Moslem relief force was moving

up towards him. Duqaq of Damascus had left his capital, with his

atabeg

Toghtekin and with Yaghi-Siyan’s son Shams and a considerable army, about the middle

of the month. At Hama the Emir joined them with his forces. On 30 December they

were at Shaizar, where they learnt that a Crusading army was close by. They

marched on at once and next morning came upon the enemy at the village of

Albara. The Crusaders were taken by surprise; and Robert, whose army was a

little ahead of Bohemond’s, was all but surrounded. But Bohemond, seeing what

was happening, kept the bulk of his troops in reserve, to charge upon the

Moslems at the moment when they thought that the battle was won. His

intervention saved Robert and inflicted such heavy losses on the Damascene army

that it fell back on Hama. But the Crusaders, though they claimed the victory

and had indeed prevented the relief of Antioch, were themselves too seriously

weakened to continue their foraging. After sacking one or two villages and

burning a mosque, they returned, almost empty-handed, to the camp before

Antioch.