A Higher Call: An Incredible True Story of Combat and Chivalry in the War-Torn Skies of World War II (25 page)

Authors: Adam Makos

Pinky greeted Charlie with a whisper. Charlie nervously faked a smile. After getting a mission under his belt, Charlie was no longer apprehensive of combat. But this time he knew he would be flying as the aircraft’s commander. He was worried, not of dying, but of messing up and taking nine other men’s lives with him. Another thought crept into his mind and propelled him forward. No man in the Army Air

Forces was forced to fly in combat. He had volunteered for this. With that came extra pay and a sense of something intangible: pride. When Charlie reported to the 8th, he had landed himself in a unit that would lose more men in the war than the U.S. Marine Corps.

Charlie grabbed a towel, his toiletries, and shuffled off to the showers in a building behind the hut. December 20 was a Monday. It was time to get to work.

T

HE AIR WAS

stinging cold as Charlie and other airmen hurried through the darkness toward the mess hall, their hands tucked into pockets of their leather jackets. Some carried flashlights because the base was still blacked out. The flashlights’ bobbing beams revealed curved Nissen huts, the prefabricated dwellings that looked like half-buried cans and served as barracks, offices, and storage containers. The men passed the base flagpole and message board, which read: “Welcome to Kimbolton, home of the 379th Bombardment Group.” Other men rode past Charlie on bicycles, dodging the neat white wooden blocks that lined the gravel streets like reflectors. A tiny light sat between the handlebars of each bike. In the darkness the lights sparkled as they converged from all directions on the long mess hall with the arched roof.

The tin ceiling above the rafters of the mess hall reflected the clatter of mess trays and silverware. Cooks sparingly ladled eggs and ham onto the trays of the bomber crewmen, knowing that most men had little appetite. The meal was primarily a formality. Most of the pilots and crews congregated around barrels of coffee and filled their mugs and thermoses.

Charlie sat with his officers, Pinky, Doc, and Andy. Andy looked meeker and more analytical than usual, and Doc tried to look cool although his eyes darted to and fro. Doc and Andy barely touched their plates. Instead they watched Charlie pick at his food and drink cup after cup of coffee. Pinky stuffed his cheeks with ham and eggs, too

inexperienced to have butterflies. The breakfast was designed to avoid serving foods with fiber. Anything that could produce gas in a man could give him the bends at altitude. They made small talk about the base’s holiday dance scheduled for that night, one that promised “Coke, beer, and women.”

When Charlie stood, his men stood with him. He led them to the briefing hut. They found the room crowded with other officers and grabbed folding metal chairs near the front. Above a small stage were two large wooden doors that hid a vast map of Europe. Lights dangled from the ceiling, upside down cones that ran from the room’s front to back. “The room has a man smell,” a navigator would write, “…leather from our jackets, tobacco, sweat, a little fear, which has its own distinctive sharpness.”

1

Around Charlie and his crew, other pilots wore their hats cocked farther than usual. The veterans’ jackets had dark, broken-in folds and whiskey stains. They tossed their white scarves as they joked and planned which pub they were going to hit after the mission. They were pros at hiding shakiness. Charlie saw colorful painted art on the backs of their jackets that glorified their planes’ names:

Nine Yanks and a Rebel

,

Anita Marie

,

Sons of Satan

, and others. Small painted bombs in neat rows spanned the back of nearly every jacket, one bomb for every mission its wearer had flown. Every man in that room was trying to reach mission twenty-five and the end of his tour. Of the 379th’s original thirty-six crews, not one had completed its tour with all ten men unharmed.

A pilot tapped the back of Charlie’s shoulder. Charlie turned and saw the jug ears and toothy smile of his flight leader, Second Lieutenant Walter Reichold, who took a seat behind him. Walt was the most popular pilot in the 379th due to his snappy New England charm. Charlie was glad he’d wound up in the 527th Bomb Squadron, the same as Walt. Walt was from Winsted, Connecticut, and in college had been the president of his fraternity, a swimmer, diver, skier, and actor, all while studying Aeronautical Engineering, something he

looked forward to resuming after the war. Walt’s jacket was bare, like Charlie’s, although Walt had flown twenty-two missions. Walt was superstitious. He was unwilling to jinx his tour by painting his jacket or even talking about his tour’s end, which Charlie and everyone knew was just three missions from being complete.

“How’d you sleep?” Walt asked Charlie.

“Logged a few hours,” Charlie said.

Walt was surprised Charlie had slept at all. Sleeping was hardest at the start of a pilot’s tour and at the end. Walt offered Charlie his flask but Charlie refused. Coming from moonshine country, he had seen how alcohol compounded people’s woes. Walt took a belt for himself and another that he said was “for Charlie.” Then he passed the flask to his officers.

The hubbub ended as Colonel Maurice “Mighty Mo” Preston, the 379th Group commander, entered the rear of the room. A captain shouted, “Ten hut.” The men sprang to their feet. Preston strode through the center aisle, already dressed head to toe in his leather flying gear, his jaw lowered like a linebacker’s. Charlie felt the air move as Preston passed by him.

Preston took his place before the mission board with an actor’s precision. He knew that in a way he was doing exactly that—acting. His job was to be larger than life to inspire the boys. It helped that he had a square jaw, thick blond hair, and that, as one officer put it, “his shoulders were square and wide as the front end of a jeep.”

2

Preston ordered the men to be at ease and seated. With a tight grin, he surveyed the room. Inspiration beamed from his eyes. Preston loved the war because he was good at it.

*

He was more than a hard-nosed commander. He was innovative. Under his leadership, the 379th had become the first group to fly in smaller, more maneuverable twelve-plane formations and the first to do multiple runs over a target

if bad weather covered the aiming point. After every mission, Preston passed out feedback forms to his pilots. He welcomed any ideas they had to improve tactics or remedy problems. With his encouragement his men even went so far as to take apart their bombsights to tweak the factory-programmed calibrations and improve the sights’ accuracy. Preston encouraged his men to have girlfriends and to live with vigor, hoping they would fly and fight that way, too. Before the war’s end, the 379th would prove him right.

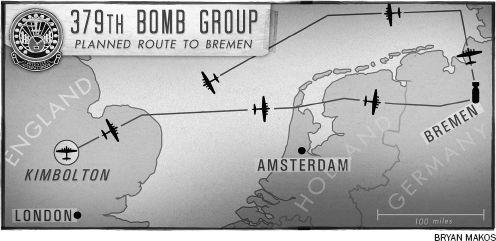

Preston nodded to his operations officer. The officer fanned open the doors and revealed the map. The mission’s course was marked with red yarn that led east across the North Sea, straight to the German city of Bremen. From there, the yarn shot ninety degrees upward into the sea before turning west and straight back to England. The men were silent. They would only groan if the target was new or deep in Germany. They knew Bremen too well, having gone there three times in the past eight days.

A grin crept across Preston’s face. “It’s nice to see no one objects to where we’re going,” he said. The men chuckled. When Preston looked at Charlie, Charlie squirmed. He wondered if Preston could sense his anxiety. The veterans around him turned silent and serious.

“The target for today,” Preston said, “is the FW-190 plant on the city’s outskirts.” Preston explained that nearly all of the 8th Air Force’s bomb groups were on the mission roster, 475 B-17s and B-24s. At the time, there were twenty-six bomb groups operational in England and twenty-three of them were going to Bremen. Friendly fighter cover had been pledged for both the road to the Reich and home. Preston warned the men that in addition to P-38 Lightnings and P-47 Thunderbolts, they might see the new P-51 Mustangs and to not shoot them down, even if they looked like Messerschmitts.

Preston stepped aside as a young intelligence officer with spectacles jumped to his feet to explain the mission’s nuts and bolts. He warned them to expect a greeting from German fighters, “maybe five hundred bandits or more.” He was careful to call them “bandits.” No one who had been in combat called the enemy “Krauts” or “Jerries,” out of an odd, fearful respect.

The intelligence officer reviewed the escape and evasion plan and told the men that if they were shot down over Germany to move toward the coast. “Try to commandeer a fishing boat there, and sail for home.” The veterans laughed at the notion of rowing three hundred miles across the turbulent North Sea. Preston did not stop their laughter—he, too, fought a smirk. He reminded the men that there would be no sailing to Sweden either. “If you have power to get to Sweden, you have power to try to get to England,” he told the men.

This time, no one laughed. Sweden was actually far closer to Germany than England. But on Preston’s map, Sweden, like Switzerland, had a big black X through it. Both were neutral countries where a bomber crew could land and receive sanctuary if their plane was badly damaged, although the crew would be interned for the duration of the war. Preston hated the idea of the safe havens and had announced that after the war he would court-martial any crew that had fled to a neutral country.

The intel captain resumed his briefing and pulled the map aside,

revealing a blackboard that showed where everyone would be flying in the twenty-one-plane battle formation. Charlie took notes before his pencil stopped when he realized he was to fly “Purple Heart Corner,” in the lowest spot in the formation and on the outside edge. Everyone knew the Germans loved to attack that spot—on the fringe—instead of barreling into the formation’s heart. Charlie had expected this—he knew his rookie crew would have to earn their way to the top.

Using a pointer, the captain made circles on the map, showing the men the flak zones and warning them that the city of Bremen was guarded by 250 flak guns and manned by “the OCS [Officer Candidate School] of flak gunners.” In other words, the men shooting at them would be the best of the best.

Someone snapped off the lights and flicked on a projector in the back of the room. The intel captain pulled down a screen and showed the men the FW-190 plant that they would bomb from twenty-seven thousand feet. He pointed out the railroad tracks that flowed into the factory.

For the next thirty minutes, Charlie watched Doc scribbling notes furiously, even though he would receive a typed sheet of notes at the briefing’s end. Charlie found himself writing the takeoff time in pen on his left palm—7:30

A.M.

—and the weather—“restricted,” with a low ceiling. Charlie knew that meant a hazardous, spiraling climb through dark clouds to reach the assembly point.

The lights flickered on. Preston stood up, looking “twenty feet tall,” as one man put it. He had saved the best news for last. Charlie expected him to mention the dance that night. “Today, gentlemen,” Preston said, “we will be leading the entire 8th Air Force—it’s a big honor for the Group and you earned it.”

Charlie saw the others grinning, so he grinned, too.

“Keep the formation tight,” Preston added. “I’ll meet you on the taxiway.”

The briefing was over. Charlie and the others snapped to attention as Mighty Mo stormed out the same way he had entered.