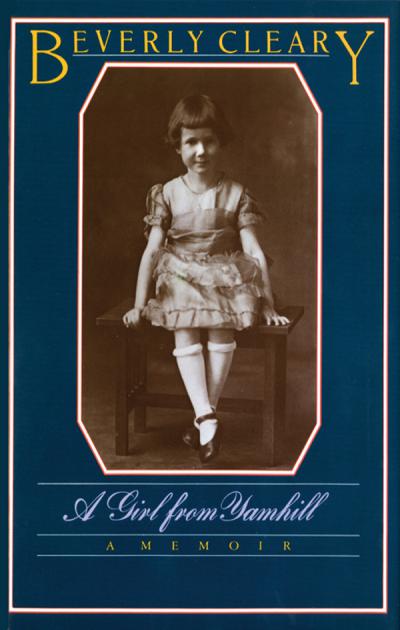

A Girl from Yamhill

A Girl from Yamhill

A Memoir

Mother and I stand on the weathered and warped back steps looking up at my father, who sits, tall and handsome in work clothes, astride a chestnut horse. To one side lie the orchard and a path leading under the horse chestnut tree, past a black walnut and a peach-plum tree, to the privy. On the other side are the woodshed, the icehouse, and the cornfield, and beyond, a field of wheat. The horse obstructs my vision of the path to the barnyard, the pump house with its creaking windmill, the chicken coop, smokehouse, machine shed, and the big red barn, but I know they are there.

Mother holds a tin box that once contained George Washington tobacco and now holds my father's lunch. She hands it to him, and as he

leans down to take it, she says, “I'll be so glad when this war is over and we can have some decent bread again.”

My father rides off in the sunshine to oversee the Old Place, land once owned by one of my great-grandfathers. I wave, sad to see my father leave, if only for a day.

Â

The morning is chilly. Mother and I wear sweaters as I follow her around the big old house. Suddenly bells begin to ring, the bells of Yamhill's three churches and the fire bell. Mother seizes my hand and begins to run, out of the house, down the steps, across the muddy barnyard toward the barn where my father is working. My short legs cannot keep up. I trip, stumble, and fall, tearing holes in the knees of my long brown cotton stockings, skinning my knees.

“You must never, never forget this day as long as you live,” Mother tells me as Father comes running out of the barn to meet us.

Years later, I asked Mother what was so important about that day when all the bells in Yamhill rang, the day I was never to forget. She looked at me in astonishment and said, “Why, that was the end of the First World War.” I was two years old at the time.

Â

Thanksgiving. Relatives are coming to dinner. The oak pedestal table is stretched to its limit and covered with a silence cloth and white damask. The sight of that smooth, faintly patterned cloth fills me with longing. I find a bottle of blue ink, pour it out at one end of the table, and dip my hands into it. Pat-a-pat, pat-a-pat, all around the table I go, inking handprints on that smooth white cloth. I do not recall what happened when aunts, uncles, and cousins arrived. All I recall is my satisfaction in marking with ink on that white surface.

Winter. Rain beats endlessly against the south window of the kitchen. I am dressing beside the wood stove, the warmest place in the house. Father is eating oatmeal; Mother is frying bacon. When I am dressed, Father sends me to the sitting room to fetch something. I run through the cold dining room to the sitting room. What I see excites me and makes me indignant. Proud to be the bearer of astonishing news, I run back. “Daddy! There's a tree in the sitting room!”

I expect my father to spring from his chair, alarmed, and rush to the sitting room. Instead, my parents laugh. They explain about Christmas trees and decorations.

Oh. Is that all? A Christmas tree is interesting, but I am disappointed. A tree slipping into the house at night had appealed to me. I want my

father to charge into the sitting room to save us all from the intruder.

Â

Memories of life in Yamhill, Oregon, were beginning to cling to my mind like burs to my long cotton stockings. The three of us, Lloyd, Mable, and Beverly Bunn, livedâor “rattled around,” as Mother put itâin the two-story house with a green mansard roof set on eighty acres of rolling farmland in the Willamette Valley. To the west, beyond the barn, we could see forest and the Coast Range. To the east, at the other end of a boardwalk, lay the main street, Maple, of Yamhill.

The big old house, once the home of my grandfather, John Marion Bunn, was the first fine house in Yamhill, with the second bathtub in Yamhill County. Mother said the house had thirteen rooms. I count eleven, but Mother sometimes exaggerated. Or perhaps she counted the bathroom, which was precisely what the word indicatesâa room off the kitchen for taking a bath. Possibly she counted the pantry or an odd little room under the cupola. Some of these rooms were empty, others sparsely furnished. The house also had three porches and two balconies, one for sleeping under the stars on summer nights until the sky clouded over and rain fell.

The roof was tin. Raindrops, at first sounding

like big paws, pattered and then pounded, and hail crashed above the bedroom where I slept in an iron crib in the warmest spot upstairs, by the wall against the chimney from the wood range in the kitchen below.

In the morning I descended from the bedroom by sliding down the banister railing, which curved at the end to make a flat landing place just right for my bottom. At night I climbed the long flight of stairs alone, undressed in the dark because I could not reach the light, and went to bed. I was not afraid and did not know that other children were tucked in bed and kissed good night by parents not too tired to make an extra trip up a flight of stairs after a hard day's work.

When I think of my parents together, I see them beside this staircase. My big father is leaning on my little mother. Sweat pours from his usually ruddy face, now white with pain, as he holds one arm in the other.

I am horrified and fascinated, for I think one arm has fallen off inside his denim shirt.

He says, “I'm going to faint.”

“No you're not.” Mother is definite. “You're too big.”

He does not faint. Somehow Mother boosts him along to the parlor couch. Later, after the doctor has gone, I learn that a sudden jerk on the reins by a team of horses has dislocated the arm, an

accident that has happened before in his heavy farm work, for his shoulder sockets are too shallow for the weight of his muscles. Mother's determination always supports him to the couch.

When I think of my father without my mother, I think of him sitting with his brothers after a family dinner. They are handsome, quiet men who strike matches, light their pipes, and as Mother said, “smoke at one another.” When their pipes are puffing satisfactorily, one of them begins, “I remember our granddad used to say⦔

I pay no attention, for I am “being nice” to my younger cousin Barbara. This is my duty at family dinners.

Father was the grandson of pioneers on both sides of his family. All through my childhood, whenever a task was difficult, my parents said, “Remember your pioneer ancestors.” Life had not been easy for them; we should not expect life to be easy for us. If I cried when I fell down, Father

said, “Buck up, kid. You'll pull through. Your pioneer ancestors did.”

I came to resent those exemplary people who were, with one exception, a hardy bunch. My Great-grandmother Bunn was rarely mentioned. I pictured them all as old, grim, plodding eternally across the plains to Oregon. As a child, I simply stopped listening. In high school, I scoffed, “Ancestor worship.” Unfortunately, no one pointed out that some of those ancestors were children. If they had, I might have pricked up my ears.

My Grandmother Bunn's parents, Jacob Hawn and his wife, Harriet, crossed the plains in 1843 in the first large wagon train to Oregon. Jacob Hawn, born in Genesee County, New York, in 1804, of German parentage, was a millwright, pioneering his life. His first wife, like so many pioneer women, died young. He then married Harriet Elizabeth Pierson. In 1834, when Jacob was thirty and Harriet sixteen, the couple left by covered wagon for outposts of civilization in need of mills for grain or lumber. In their covered wagon, they trundled to Wisconsin, Missouri, Texas, Louisiana, back to New York, and then continued on to Missouri once more. Four children were born along the way. On May 18, 1843, the family started for Oregon with a company

of “three hundred souls all toldâ¦traveling by compass due West.”

In her old age, Laura Aurilla, the eldest child, recorded her memories of that journey to Oregon with her family, “two yoke of oxen, two horses and a cow.” She was eight years old. Her little brothers were six, three, and one month old. My great-grandmother was by then twenty-five.

Laura described the company as “a happy lot of people, all of one mind to go to the new country called Oregon.” There was no sickness or fear of Indians, and in the beginning there was plenty of grass for cattle. Laura recorded that the prairie was black with buffalo. If an animal was killed, it was divided with every family and the hide saved for future use.

Laura wrote about the hazards of crossing the Platte River and of help from Indians, of bare country with buffalo chips the only fuel for cooking, and of trading with Indians for dried meat and salmon.

When food ran low, families camped off to themselves to prevent hungry children from teasing for what others might have. (“Never tease and never hint” was a pioneer rule handed down to me.) Everyone was relieved when they were able to buy flour at Fort Hall and to bathe and wash clothes at Soda Springs. The Nez Percé

Indians were good to the “Bostons,” as Indians called the members of the wagon train.

Laura described the men cutting timber and clearing a road to cross the Rocky Mountains, and how her father “fixed up” the mill of Dr. Marcus Whitman, the missionary. When the wagon train reached the Columbia River in November, some travelers built rafts, while wagons and livestock were sent overland. Others, including the Hawns, bought canoes from Indians.

By November, Oregon was cold and rainy. The Columbia River and the Gorge, a funnel for raw winds, were full of rapids. Clothes were wet, the family hungry. When they were blown ashore, my great-grandfather built a fire and vowed to find food, “dead or alive.” With a sharpened stick, he speared two salmon from a stream where the fish, “running upstream, were so thick their backs were out of the water.” The family ate roast salmon “with no salt, pepper or bread” before they traveled on, walking around rough water and towing their canoe.

Laura recalled how hard they had to work to bail water out of the canoe, and how, on reaching Fort Vancouver, then a British settlement, at night, they nearly swamped the canoe. “Just then a man hailed us, âWho comes there?' By this time Father was out of humer [

sic

], and told him it was none of his business.”

The Hawns then learned that Dr. Whitman had sent an Indian ahead bearing the news that a millwright was on the way. The man, hired to hail everyone who came along, stood on a rock in the rain and cold for four days and nights waiting for Jacob Hawn, the millwright. “So our hardships were ended,” Laura wrote.

With provisions supplied by Dr. John McLoughlin, the missionary, the family was taken to Oregon City, where millstones shipped around Cape Horn were waiting to grind the harvest into flour for arriving emigrants. Dr. McLoughlin put men to work building a house for the family while, under Jacob's supervision, others constructed the mill, the first in what would become, in 1859, the state of Oregon.

Â

There is not a word of self-pity. Laura never refers to herself, only to “we.” She was often tired, cold, and hungry, but so was everyone else. She must have taken responsibility for her little brothers, not easy when a foal, the first stallion in Oregon, was loaded into the wagon with the children. Hardship was to be expected when one was a pioneer. All her life she remembered that journey with wonder, and with pride at the part she had played in the history of the United States.

Jacob Hawn took up a plot of land near Oregon

City, later moving near Lafayette. He built grist mills and bridges in the Willamette Valley. He also built the Lafayette Hotel, sometimes called Hawn's Tavern, which was used for court sessions and religious services. It also became a schoolhouse, for Harriet provided a room for a school and room and board for a young man eager to teach. Jacob acted as postmaster while continuing to build grist and lumber mills. He died in 1860, at the age of fifty-six, of “the hemorrhage.”

Harriet Hawn must have been a woman of strength and endurance. Before the death of her husband, she bore four more daughters, one of whom, Mary Edith Amine, was to become my grandmother.

Widowed, Harriet moved with her children to The Dalles, then a rough mining town, where she built a hotel. She lived in The Dalles until she died, apparently enjoying her hard life.

The Bunn side of my father's family was considered less interesting, the Johnny-come-latelies of the family, for Great-grandfather Frederick Bunn did not cross the plains until 1851. To the surprise of my generation, the Bunns are now better known than the Hawns because of the house in Yamhill, now an Oregon landmark.

Frederick Bunn was born in Murfreesboro, Tennessee, in 1825. He and his brothers and sisters were orphaned and divided among families

who could take an extra child. Frederick was reared by a Mr. Wright in Texas, but in 1851 returned to Missouri, where he married Elmira Noel. A wife was a valuable asset, for in 1850 the Donation Land Act had been changed to entitle a married man to twice as much land as a single man.

The couple set out for Oregon, a journey of great hardship for Great-grandmother Bunn. She became pregnant, and Indians, who had been friendly and helpful to the Hawns in 1843, had turned hostile by 1851. To be eighteen, pregnant, terrified, and living in discomfort and hardship was too much for the young woman to bear. Her only child, my grandfather, John Marion Bunn, was born in Carlton, Oregon, nine months after the beginning of the long, hard journey. Elmira became an invalid who lived in terror of Indians all her life, even though the Indians were often imaginary.

John Marion Bunn married Mary Edith Amine Hawn on September 30, 1872. They bought land in and around Yamhill and a wheelwright's house that they enlarged into the first fine house in Yamhill. They had ten children, eight of whom survivedâfive boys and three girls. The farmhouse at the time of my father's boyhood held three generations and was a lively place.

My father told one story of growing up in Yam

hill. When he was fifteen, his father sent him to the butcher shop to buy some beefsteak. Instead of buying the meat, he continued, by what means I do not know, to eastern Oregon, where he worked on ranches all summer.

When I once asked my Grandmother Bunn if she had worried about my father when he did not return, she answered, “Oh my, no. We knew he would turn up sooner or later.” Turn up he did, three months later.

All his father said was “Did you bring the beefsteak?”