A Framework for Understanding Poverty (13 page)

Read A Framework for Understanding Poverty Online

Authors: Ruby K. Payne

We agree to disagree.

USING METAPHOR STORIES

Another technique for working with students and adults is to use a metaphor story. A metaphor story will help an individual voice issues that affect subsequent actions. A metaphor story does not have any proper names in it and goes like this.

A student keeps going to the nurse's office two or three times a week. There is nothing wrong with her. Yet she keeps going. Adult says to Jennifer, the girl, "Jennifer, I am going to tell a story and I need you to help me. It's about a fourth-grade girl much like yourself. I need you to help me tell the story because I'm not in fourth grade.

"Once upon a time there was a girl who went to the nurse's office. Why did the girl go to the nurse's office? (Because she thought there was something wrong with her.) So the girl went to the nurse's office because she thought there was something wrong with her. Did the nurse find anything wrong with her? (No, the nurse did not.) So the nurse did not find anything wrong with her, yet the girl kept going to the nurse. Why did the girl keep going to the nurse? (Because she thought there was something wrong with her.) So the girl thought something was wrong with her. Why did the girl think there was something wrong with her? (She saw a TV show ... )"

The story continues until the reason for the behavior is found, and then the story needs to end on a positive note. "So she went to the doctor, and he gave her tests and found that she was OK."

This is an actual case. What came out in the story was that Jennifer had seen a TV show in which a girl her age had died suddenly and had never known she was ill. Jennifer's parents took her to the doctor, he ran tests, and he told her she was fine. So she didn't go to the nurse's office anymore.

A metaphor story is to be used one on one when there is a need to understand the existing behavior and motivate the student to implement the appropriate behavior.

TEACHING HIDDEN RULES

For example, if a student from poverty laughs when he/she is disciplined, the teacher needs to say, "Do you use the same rules to play all computer games? No, you don't because you would lose. The same is true at school. There are street rules and there are school rules. Each set of rules helps you be successful where you are. So, at school, laughing when being disciplined is not a choice. It doesn't help you be successful. It only buys you more trouble. Keep a straight face and look sorry, even if you don't feel that way."

This is an example of teaching a hidden rule. It can be even more straightforward with older students. "Look, there are hidden rules on the streets and hidden rules at school. What are they?"

After the discussion, detail the rules that make students successful where they are.

WHAT DOES THIS INFORMATION MEAN IN THE SCHOOL OR WORK SETTING?

a Students from poverty need to have at least two sets of behaviors from which to choose-one for the street and one for the school and work settings.

? The purpose of discipline should be to promote successful behaviors at school.

a Teaching students to use the adult voice (i.e., the language of negotiation) is important for success in and out of school and can become an alternative to physical aggression.

? Structure and choice need to be part of the discipline approach.

r Discipline should be seen and used as a form of instruction.

CHAPTER 8

Instruction and Improving

Achievement

ne of the overriding purposes of this book is to improve the achievement of resources, and numerous studies have documented the correlation J of students from poverty. Low achievement is closely correlated with lack between low socioeconomic status and low achievement (Hodgkinson, 1995). To improve achievement, however, we will need to rethink our instruction and instructional arrangements.

ne of the overriding purposes of this book is to improve the achievement of resources, and numerous studies have documented the correlation J of students from poverty. Low achievement is closely correlated with lack between low socioeconomic status and low achievement (Hodgkinson, 1995). To improve achievement, however, we will need to rethink our instruction and instructional arrangements.

TRADITIONAL NOTIONS OF INTELLIGENCE

For years, and still very prevalent, is the notion that nearly all intelligence is inherited. In fact, the book The Bell Curve purports that individuals in poverty have on the average an IQ of nine points lower than individuals in the middle class. That might be a credible argument if IQ tests really measure ability. What IQ tests measure is acquired information. Try the following IQ test and see how you do.

IQ TEST

1. What is gray tape and what is it used for?

2. What does dissed mean?

3. What are the advantages and disadvantages of moving often?

4. What is the main kind of work that a bondsman does?

5. What is a roach?

6. How are a pawnshop and a convenience store alike? How are they different?

7. Why is it important for a non-U.S. citizen to have a green card?

8. You go to the bakery store. You can buy five loaves of day-old bread for 39 cents each or seven loaves of three-day-old bread for 28 cents each. Which choice will cost less?

9. What does deportation mean?

10. What is the difference between marriage and a common law relationship?

These questions are representative of the kinds of questions that are asked on IQ tests. This test is only different in one way: the content. Yet it illustrates clearly the point that the information tested on many IQ tests is only acquired knowledge. IQ tests were designed to predict success in school. However, they do not predict ability or basic intelligence. If middle-class students were to take this (invalidated) test, they could possibly have nine IQ points fewer than many students in poverty. Therefore, the assessments and tests we use in many areas of school are not about ability or intelligence. They are about an acquired knowledge base; if your parents are educated, chances are you will have a higher acquired knowledge base. A better approach to achievement is to look at teaching and learning.

DIFFERENTIATING BETWEEN TEACHING AND LEARNING

The emphasis since 1980 in education has been on teaching. The theory has been that if you teach well enough, then learning will occur. But we all know of situations and individuals, including ourselves, who decided in a given situation not to learn. And we have all been in situations where we found it virtually impossible to learn because we did not have the background information or the belief system to accept it, even though it was well-taught and presented.

In order to learn, an individual must have certain cognitive skills and must have a structure inside his/her head to accept the learning-a file cabinet or a piece of software. Traditionally, we have given the research on teaching to teachers and the research on learning to counselors and earlychildhood teachers. It is the research on learning that must be addressed if we are to work successfully with students from poverty.

Teaching is what occurs outside the head.

Learning is what occurs inside the head.

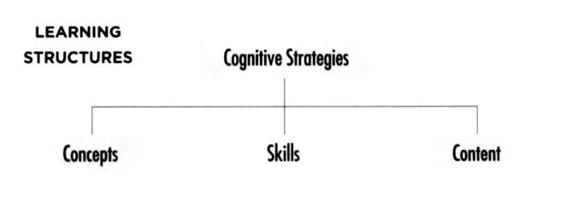

In this oversimplified representation of a learning structure are four elements. The first is Cognitive Strategies. These are even more basic than concepts. They are fundamental ways of processing information. They are the infrastructure of the mind. Concepts store information and allow for retrieval. Skills-i.e., reading, writing, computing, language-comprise the processing of content. Content is the "what" of learning-the information used to make sense of daily life. Traditionally in schools we have assumed that the cognitive strategies are in place. If they are not, we test and place the student in a special program: special education, dyslexia, Chapter i, ADHD, 504, etc. Little attempt is made to address the cognitive strategies because we believe that to a large extent they are not remediable. We focus our efforts in pre-K and K on building concepts. We devote first through third grades to building skills. We enhance those skills in grades 4 and 5. And when the student gets into sixth grade, and on to 12th grade, we teach content.

The truth is that we can no longer pretend this arrangement worksno matter how well or how hard we teach. Increasingly, students, mostly from poverty, are coming to school without the concepts, but more importantly, without the cognitive strategies. We simply can't assign them all to special education. What are these cognitive strategies, and how do we build learning structures inside the heads of students?

COGNITIVE STRATEGIES

Compelling work in this area has been done by Reuven Feuerstein, an Israeli. He began in 1945 working with poor, disenfranchised Jewish youths who settled in Israel after World War II. He had studied under Jean Piaget and disagreed with Piaget in one major way. He felt that between the environmental stimulus and the response should be mediation (i.e., the intervention of an adult).

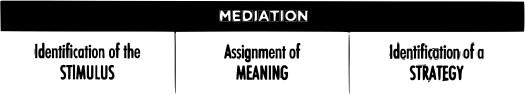

Mediation is basically three things: identification of the stimulus, assignment of meaning, and identification of a strategy. For example, we say to a child, "Don't cross the street. You could get hit by a car. So if you must cross the street, look both ways twice."

WHY IS MEDIATION SO IMPORTANT?

Mediation builds cognitive strategies, and those strategies give individuals the ability to plan, systematically go through data, etc.

If an individual depends upon a random, episodic story structure for memory patterns, lives in an unpredictable environment, and has not developed the ability to plan, then ...

If an individual cannot plan, he/she cannot predict.

If an individual cannot predict, he/she cannot identify cause and effect.

If an individual cannot identify cause and effect, he/she cannot identify consequence.

If an individual cannot identify consequence, he/she cannot control impulsivity.

If an individual cannot control impulsivity, he/she has an inclination toward criminal behavior.

Feuerstein identified the missing links that occur in the mind when mediation had not occurred. These students by any standard would have been identified as special-education students. Yet, with his program, many of these students who came to him in the mid-teens went on to be very successful, with some even completing Ph.D.s. To teach these strategies, Feuerstein developed more than 50 instruments. What are these missing cognitive strategies?