A Dark and Distant Shore

Read A Dark and Distant Shore Online

Authors: Reay Tannahill

For Josephine and Norman Harris,

in affectionate memory

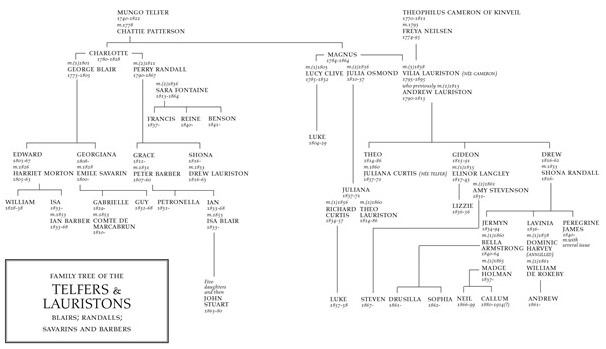

Click or touch image to enlarge

1803

1

When Mungo Telfer saw Kinveil for the first time, it was a brilliant day in the early summer of 1803, crisp and fresh and new-minted, with neat white clouds chasing one another from west to east across a blue, blue sky.

Even the sardonic private voice that, for all the sixty years of Mungo’s life had held his imagination in commonsensical check, fell silent – for there, a thousand feet below the summit on which he sat, saddle sore and more than a little weary, was his heart’s dream translated into reality. Floating above its image in the blue and silver sea lay a sturdy island castle, proud and solitary against a background of mountains that, at this season of the year, were draped majestically in velvet, in every conceivable tone of green and purple and indigo. Mungo sat and looked, the reins loose in his hands, and could have wept with happiness.

He was a small, tough man with pale eyes, a nose that sprang from his forehead like the prow of a ship, and a chin that had become alarmingly firm and not a little pugnacious during the years that had transformed him from a penniless Glasgow urchin into one of the great merchant venturers of his day. Though still plain ‘Mister Telfer’, he was recognized in his native city and far beyond as one of that acute, hard-headed, obstinate, and extremely rich body of men known, because of their trade with Virginia, as the Tobacco Lords. But hard-headed or not – and, as he wryly admitted, against all the laws of probability – he had contrived to cling to his own special, sentimental vision of the land that bore him. Other great merchants might be ambitious of becoming civic dignitaries, or cultural pillars of the Sacred Music Institution or the Hodge Podge Club, or sleek country gentlemen with an interest in the new agriculture. But not Mungo Telfer. He knew what he wanted, what he had always wanted. A home steeped in five hundred years of Highland history, a castle set amid the most romantically picturesque scenery in the world. And now he was going to have it. There was no question in Mungo’s mind. Whatever it cost him, he was going to have Kinveil.

His son Magnus drew rein beside him. Magnus was nineteen years old, tall, handsome, and indolent – and who he had inherited his indolence from Mungo couldn’t imagine. Certainly not from him. Mungo glowered at the boy as he cast a dispassionate gaze over the magnificent panorama spread out before them and drawled, ‘Devilish isolated, isn’t it!’

George Blair, Mungo’s son-in-law and another trial to him, was still plodding phlegmatically up the slope behind. Mungo closed his eyes for a moment, and then, opening them, exclaimed, ‘Well, come on, then! Are you not in a hurry for the fine lunch the laird has waiting for us?’

The laird came as something of a surprise to Mungo, for although George Blair lived only forty miles away and was a great one for facts and figures, he was decidedly weak on insights. All he had said about Kinveil’s present owner was, ‘Foreign kind of fellow, head over heels in debt. His father was exiled for years after the ’Forty-five rebellion, and the present man was raised abroad somewhere.’ Mungo had deduced that he shouldn’t expect a tartan savage, but he had not expected quite such a cosmopolitan gentleman as Mr Theophilus Cameron turned out to be, tall, slender, elegant, and not much above thirty.

It didn’t matter, of course. There wasn’t a trick of the huckstering trade that Mungo didn’t know, and he soon discovered that Mr Cameron had only one of them up his slightly frayed sleeve. While it seemed that he was resigned to parting with his ancestral acres, he wasn’t going to swallow his

noblesse oblige

and part with them to a social inferior unless the price was very right indeed. Subtly, it was conveyed that Mr Cameron, whose pedigree stretched back into the mists of time, knew that Mr Telfer’s pedigree didn’t stretch anywhere at all.

Except to the bank in Glasgow.

With amusement, and quite without resentment, Mungo noticed the laird’s dilatory arrival at the water gate to welcome his visitors. And the lunch consisted of smoked salmon, the everyday fare of the glens, instead of fresh; salty butter that wasn’t far off rancid; oatmeal bannocks that would have been the better for warming through; no French wines, but a fair whisky. Though even that was served neat instead of in the genteel form of whisky bitters. Afterwards, the condescension became more obvious. The laird summoned a groom to show Magnus and George the Home Farm, and rang for his steward to escort the prospective buyer round the castle itself.

No one had tried to put Mungo in his place for many a long day, and he rather enjoyed it. Cheerfully, he looked forward to a good, satisfying haggle.

What threw Mungo quite out in his reckoning was the seven-year-old daughter of the house, a waist-high bundle of fair-haired, green-eyed animosity.

They met on the open stairs leading from the central courtyard up to the sea wall.

Mungo wasn’t very good at children. He beamed at her in an avuncular kind of way, and said, ‘Hullo, lassie.’

The lassie, pinafored, shawled and bonneted like some old henwife, fixed him with a sizzling glare and said in a light, tight voice, ‘Are you the man who wants to buy Kinveil?’ There was no accent, apart from a hint of sibilance on the ‘s’.

‘Aye.’

‘Why?’

He was disconcerted. ‘I like it here.’

‘So do I.’ Her chin came up belligerently.

Mungo stared back at her and, after a moment, tried again. ‘But surely you’d like to see some big cities for a change? Glasgow, maybe. Or London.’

‘No. I like it

here.

’ Her lips quivered a little. ‘I

love

it here.’

He took her hand and patted it, feeling the resistance. ‘But that’s because you don’t know anywhere else,’ he said reasonably. ‘Just think! You might even see the king and queen.’ On reflection, George III and his starchy consort were hardly such stuff as childish dreams were made on. ‘Beau Brummell,’ he volunteered more hopefully. ‘And the Prince of Wales.’

‘Prince of

Whales

!’

she exclaimed scornfully. ‘I don’t wish to be acquainted with such people.’

He gave up. ‘Never mind. I’m sure your da will take you somewhere fine.’

There was calculation, he thought, in the clear green eyes. ‘There’s nowhere as fine as here. Come, let me show you.’

Obediently, he allowed himself to be led up to the battlements. The wall was crumbling, he noticed, and wondered what it was going to cost him to have it repaired.

His eyes followed her pointing finger.

‘Look out there to the west. That’s the island of Skye.’ She pointed again. ‘And those mountains in the south are the Five Sisters. And over there... Oh, look! There’s a herring gull dropping a mussel on the rocks to break the shell.’ She leaned over the parapet. ‘And look down below here. There’s a...’

He sensed the violent, seven-year-old push before he felt it, and was braced. His grip on the parapet scarcely even shifted.

He hesitated for a moment, and then turned to confront her. She was breathing fast, and her cheeks were pink with a combination of rage and fear.

The steward scuttled up the stairs towards them, his mouth and eyes round with horror. ‘Miss Vilia! Miss Vilia!’

Mungo said conversationally, ‘That’s a bonny name. Is it Highland?’

The child swallowed. ‘Norwegian.’

‘Oh, aye?’ He shook his head at her kindly. ‘That’s not the way, you know. You’re too wee, and I’m too heavy.’ He touched a finger lightly to her brow. ‘You’ll have to use your head to get what you want. But you’ll learn. You’re a spunky wee thing.’ A smile tugged at the corner of his mouth, and he held out his hand. ‘Pax?’

And that was a silly question, he thought. She’d not know what it meant.

She did. Hands behind her back, she gave him a wide, green, empty stare, and then turned and ran down the stone staircase. He was not to see her again for nine years – except once, from a distance.

When the steward, still mouthing profuse and incoherent apologies, took him back to Mr Cameron, who was waiting in the Long Gallery, Mungo settled for £10,000 more than he had intended to pay.

After seeing his visitors off at the water gate next morning, Theo Cameron returned to his study to find his daughter waiting for him. Once, when she was four years old, he had said to her, ‘I do not care to see you looking like some tinker’s brat. Oblige me by dressing in a more ladylike fashion.’ So now, when she knew she was likely to see him, she did. Personally, she thought her one ‘good’ dress quite horrid. It was of crêpe, in a dusty pink colour with a flounced shoulder cape and dark blue ribbon trim, and no improvement at all on her usual homespun. But today she had more important things on her mind than her nurse’s hopeless eye for colour.

Not until yesterday morning had she heard as much as a hint of her father’s plan to sell Kinveil, and it hadn’t been he who told her, but Meg Macleod, the nurse who had mothered her since she was born. The servants had known for weeks, as servants always did.