A Company of Heroes Book Four: The Scientist (3 page)

Read A Company of Heroes Book Four: The Scientist Online

Authors: Ron Miller

The day was a bright one in late spring and Bronwyn could feel the sun on her skin as it penetrated the light fabric of her gaily-patterned cotton frock. She sat on the cool, close-cropped grass by the water’s edge, hugging her long legs, her firm, square chin resting on her knees. After much relunctance, she had finally adopted the current fashion of going stockingless in the spring and summer, at least when dressed casually. Even though her skirt covered her prolonged legs to a point somewhat lower than mid calf, she still felt self-consciously overexposed, a relic of her puritan upbringing. She thought it vaguely indecent to see her toes brazenly revealed at the end of her sandals, wriggling with an abandon she seldom felt herself. These inhibitions were not a little mitigated by the congenial caresses of warm sun and faint breeze on her skin. She had recently begun to allow her hair to again grow long and it was now just greater than shoulder length; as she looked down into the water, it was as from within a terra cotta grotto. The grotto smelled of sandlewood soap. Even though she was sitting in the open, within plain sight of one or two hundred people, depending upon how many cared to notice and who one chose to count, she felt as though she were hidden within that fragrant grotto, invisible as a sigh, a daydream or a heartbeat. Blackie cruised by like a patrolling ironclad, trailing blue ripples like silken pennants.

Here I go, feeling lonely again; how can I be so damned maudlin? Can nothing go so right for me that I cannot eventually find

some

fault with it? There’s not a reason in the world why I shouldn’t be as happy as anyone has any right to be. Maybe more so. It just seems that some part of me is convinced that somewhere in all of this contentment there’s a scab and that if I pick at it enough I’ll discover the original wound underneath.

She sighed and wondered where Gyven was. She had been seeing him less and less often and, as was her wont, outwardly vilified him for his inattention while inwardly wondering what she had done to drive him away. It was becoming habitual to assume that the blame must fall on her broad shoulders: an old habit to which she had not reverted for a very long time, a remnant of days in the old palace at Blavek where she had grown up, trained as carefully and callously as a kind of human bonsai. There she had been assiduously and meticulously molded to fit her traditional place in the world, the rôle of royal princess, an occupation that required little in the way of intelligence, talent or competence: a perfect woman in the eyes of Musrum. At the same time she was forced to watch her brother Ferenc, the future king, inept both morally and intellectually, treated with the deference and attention she knew in her heart she deserved and that he received solely by virtue of his sex and birthdate. Her natural contrariness and conceit had acted to protect her from completely absorbing and sharing in a generally accepted image of herself that was both degraded and degrading, much in the same way that a duck’s oily feathers shed water from its body, but a dozen and a half years of relentless indoctrination nevertheless had its inevitable effect, wearing down even her adamantine ego as surely as the waves will erode a cliff face, or drop of detergent will sink a duck. Even today, years after she had fled her homeland, many of the old ingrained uncertainties would periodically resurface, like malarial fevers, popping up to disturb the placid surface of her ego like fetid bubbles of methane percolating from the decaying vegetation at the bottom of a pond.

It would be nice to have had Gyven around when she was feeling like this; he was as solid as a rock, predictable, safe and secure. He made her fears and shakey self-esteem seem trivial and inconsequential; they shattered against his rocky flanks like breaking waves. But as she compared herself to an ocean, it never occured to her that a sea had no need for its shores, whose only purpose was confinement. She never equated the thundering of breakers with the sound of a prisoner beating against the door of her cell.

Gyven’s interest in travel had waned once he and the princess had arrived in Londeac. She had supposed that anyone who had spent the first thirty-odd years of his life buried in a cavern would be anxious and curious to see what the outside world was like. Certainly, at first, Gyven seemed to be fascinated with every aspect and variety of the continent’s landscapes. But it was as though his world gradually inverted upon him; he developed more of a claustromania than an agoraphobia. He grew ever more taken with visiting caves, grottoes, basements, cellars, quarries and excavations and, eventually, mines, tunnels and caissons.His great knowledge of geology and mineralogy was sought out and appreciated by the engineers involved and the sudden demand for his advice as an expert consultant was his plausible and reasonable excuse for accepting every one of their invitations.

His visits to Toth and the palace became infrequent; when he was home he was distracted, dreamy, incommunicative. He seemed only aware of Bronwyn when she made love to him . . . which she came to realize was just another manifestation of that invisible, mysterious impediment: she had for a long time been having sex with him; she wasn’t certain exactly when they had ceased making love.

Gyven had been gone now for an entire month, his longest absence yet and the first during which she had no idea where he had gone. He had merely disappeared one morning and there had been no word since. The disturbing thought was that she had begun to wonder if she even missed him. And if she did, did she miss

him

, or did she just miss his solidity, as a ship might miss its anchor? Never did she give even so much as a passing thought to returning to her homeland. Within days of her abdication, in fact, before the last of Tamlaght disappeared beyond the horizon, as her ship anxiously steamed for Londeac, the armies of Crotoy poured unhindered across the northern border and occupied that relatively uninhabited quarter. A desultory kind of war was now being raged in which the small, poorly-equipped, -supplied and -trained Crotoyan army was faced only by the already ravaged and weary people of Tamlaght, something like a normally inocuous disease being able to overcome a dibilitated body. The results of Payne Roelt’s reign of terror had already depressed the princess enough and she had no particular desire to see her country and its people even further devastated. The answer that seemed perfectly adequate to her was to turn her back on the whole unpleasant mess.

There was the sound of a gong and one of the swans honked either in reply or in protest. It was the signal that the luncheon hour had arrived and the workers were allowed to take their break. She sighed again, stood and stretched. She was a very tall young woman, a little over twenty years old, who when stretched as she was at full length could easily let her fingertips touch a point (had there been one available) considerably more than eight feet over her head. She was inordinately leggy (the professor had once calculated that they comprised 57% of her total length), as sleek and supple as a strand of kelp, with the hydrodynamic streamlining of an eel or barracuda. She had a lean, pale face that was home to eyes as metallic green as a pair of bottle flies. Except in coloring and some more or less minor physical details, she greatly resembled at least as a general type her friend Rykkla Woxen, perhaps in the same way a greyhound resembles a coyote. Like Rykkla, the princess was abnormally tall, snakily athletic (undeservedly so, for unlike Rykkla she loathed physical exercise), with an aquiline nose set as firmly as a dolmen in an angular, bony face. The net effect was rather sharp and hawkish. Her mouth was wide, with perhaps just the slightest hint of an overbite making her smile radiantly toothy. Her hair was mahogany, a helmet of corroded iron, counterpointed by a porcelain coloring that ranged from the palest, most translucent tints in her skin to the most luminous hues in her hair, in short, if Rykkla was a work in oils she was a study in watercolor. Her complexion was like a pitcher of cream into which a single drop of blood has fallen. But where Rykkla was as graceful in everything she did as a heron in flight, Bronwyn was as awkward and clumsy as one on land.

The good eye of an agéd gardener, weeding the flower beds on the far side of the pond, was caught by the figure of the princess, backlit by the brilliant sun, her pale yellow dress transformed into an illuminated nimbus, a lambent vapor that surrounded the bifurcated silhouette of the slim, swaying body, much like a bar of white-hot iron might be swathed in swirling, incandescent gasses. The gardener, who had long ago believed himself beyond the age for such yearnings, swallowed hard against the sudden, unfamiliar, long-forgotten lump that rose in his throat, the stirring of his few unexpectedly surviving, nearly-atrophied hormones. He watched, unmoving, almost unbreathing, as Bronwyn turned and with long, lazy strides drifted back toward the Academy, her rhythmic figure sleepily undulating like the prayerful cobra. The gardener retired his tools and went home early that day, not certain if he were happier or unhappier than he had been in a very long time, but his once cozy little hovel had never before looked so hollow and lonely.

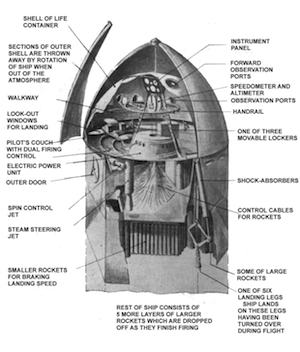

The shed where the life compartment was being constructed was a barn-like structure with a completely open and unobstructed interior. The capsule itself sat in the middle of the vast expanse of wooden floor, surrounded by a confused welter of shop tools, benches and construction materials, to say nothing of two or three dozen workmen and technicians. Its squat, domed shape stood several feet higher than Bronwyn’s head, while the hexagonal power unit that would eventually be attached to its lower part was separately under construction to one side.

Where the main rocket was hexagonal in cross-section, the life compartment had a circular base; all of its curves were designed, the professor had explained, to withstand the pressure of its internal atmosphere once it reached the vacuum of outer space. The upper third of the dome was pierced by a ring of small circular deadlights and midway down the side was a larger circular manhole that would eventually be plugged by a substantial semipermanent hatchcover. Beneath was a second smaller manhole that would allow ingress and egress once in an airless environment.

When she stepped through the wide doorway of the hangar, open against the rising heat of the day, she was greeted by the shop foreman, an engineer named Petro Zirconis. Perhaps of all the scientists at the Academy, Zirconis was the most passionate about the imminent launch of the giant rocket; he devoted himself to its construction with the zealousness normally devoted by the faithful to the erection of a temple, which perhaps he was and it was. A small, compactly-built man, with a large nose and popeyes and a nervous, distracted air, as though he were perpetually afraid he was missing the gist of some joke, he welcomed Bronwyn with earnestness and a quick, tentative half-chuckle, just in case her reply might have been a funny one.

“It looks nearly finished, Petro,” she said.

“It is, Princess, it is,” he replied in a hushed tone. “The Work is almost complete.”

“Wittenoom will be ready to launch in just a week or so, I think, judging from how well things seem to be going.”

“Yes, yes,” Zirconis muttered, already disinterested in the conversation. He drifted away from the girl and resumed his interrupted work which, at the moment, was the discussion of some complex point or another with one of the engineering draftsmen, who had a sheaf of rolled-up paper tubes under one arm. Bronwyn wandered unhindered over to the capsule. A short wooden ladder had been placed against the inwardly sloping surface, its top reaching the larger manhole; she mounted it and poked her head into the space vessel’s interior. It was garishly illuminated by an electric light, which revealed a confused welter of open gridworks, structural members, festoons of wire, cables and piping, interim wooden planking and almost nothing that made much sense to her.

The life compartment’s propulsion unit was more interesting and appeared to be virtually complete. It was an hexagonal box about fifteen feet tall standing on spidery-looking tubular legs that unfolded from each of the six corners. These, she knew, would be collapsed against the sides of the spacecraft during the launch and flight through space and would not be deployed until needed for the landing on the moon. Since the legs raised the propulsion unit off the floor by several feet she was able to look beneath it. Visible were the 1,050 circular openings of the medium and small rockets that would enable the space flyers to cancel their enormous velocity and descend safely onto the lunar surface. Above these, she knew, was the bank of 600 small rockets necessary to escape the moon’s lesser gravity for the return to the earth. It made her skin crawl when she realized that the rocket tubes were in place and that the slightest provocation might be sufficient to ignite them, incinerating her as efficiently and completely as a bug under a blowtorch.

As she stood erect she appreciated with a kind of unexpected certainty how close to realization the project actually was; its abstraction evaporated suddenly, leaving her chilled and uncertain of her mood.

Wittenoom’s really going to do it!

she thought, feeling as though someone had just plucked her spine, twanging it like the string of a violin . . . pretty much as Rykkla was almost simultaneously experiencing the same unpleasant phenomenon.